Did volcanoes pack enough punch to do the dinosaurs in?

Loading...

What killed the dinosaurs?

According to the reigning hypothesis, first proposed in the 1970s, the dinosaurs' extinction, along with that of nearly three in four plant and animal species on Earth, was triggered by a Manhattan-sized asteroid slamming into what is today the Yucatán Peninsula about 65 million years ago.

But wait, there might be more to the extinction story.

Volcanic eruptions may have also played a role. Around the same time as the Yucatán impact, the other side of the world was also acting up. Perhaps as a consequence of the asteroid, massive volcanic eruptions rocked the Deccan Plateau, ejecting vast amounts of sulphur dioxide and other gases into the atmosphere, blotting out the sun and cooling the Earth's surface.

So was it the asteroid, the volcanoes, or some combination of the two?

Volcanologists previously thought the huge volumes of sulphur dioxide emitted during continental flood basalt eruptions would cause significant climate cooling and acid rain, enough to kill off plants and animals around the world. But a new study suggests that the volcanoes produced a less severe result.

“These eruptions can have some effect on climate, but it’s less grim than previously thought,” study lead author Anja Schmidt tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview. These findings are described in a paper published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“They’re still significant,” says Dr. Schmidt, a volcanologist at the University of Leeds. The sulphur emissions could cause a temperature change of as much as 4.5 degrees Celsius (8.1 F).

“But,” she adds, “we also find that these temperatures will recover to normal quite quickly once an individual eruption stopped.” In fact the temperatures will bounce back within 50 years of the end of the eruption, which is probably not long enough to have a significant impact on species around the globe, according to their research.

The sulphur emissions also lead to acid rain. In what Schmidt describes as one of the most surprising results of the research, the scientists found that acid rain would have strong effects only on plants in some parts of the world. “So it’s very difficult to explain these global scale biotic crises with acid rain,” she says.

Still, “There’s this interesting pattern where many flood basalt eruptions in the past 500 million years seem to coincide with mass extinctions,” University of California, Berkeley Department of Earth and Planetary Science postdoctoral researcher Benjamin Black, who was not involved in the study, tells the Monitor in an interview.

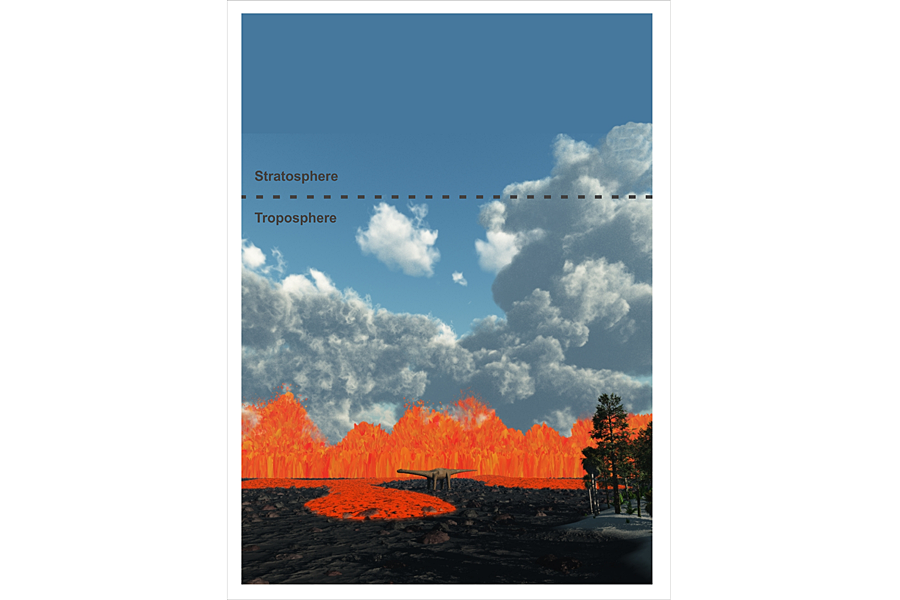

Continental flood basalt eruptions are not like the explosive eruptions of more modern times. In these ancient eruptions, lava flows in a sort of fountain out of the ground that volcanologists call a "curtain of fire."

While explosive eruptions last hours or a couple of days, flood basalt eruptions last much longer, stretching on for years or even decades. These eruptions produce a significant volume of lava and volcanic gases, like the sulphur in question.

“One of the volcanic gases that volcanoes can release is sulphur, usually in the form of sulphur dioxide,” explains Dr. Black. “Sulphur is known to do two things. It can cause cooling if it gets into the stratosphere and forms aerosol particles,” which would reduce surface temperatures, he says, “and sulphur can also deposit out of the atmosphere and it will be in the form of an acid.”

The researchers looked at two major eruptions: the Roza eruption that happened about 14.5 to 16.5 million years ago, and the Deccan Traps from about 65 million years ago. The timing of the Deccan Traps eruption seems to align with the mass extinction that saw the end of the dinosaurs.

A series of flood basalt eruptions produced the Deccan Traps over the course of about a million years. With all that lava produced, the Deccan Traps covered about one-third of what is now India.

A recent study suggested a combination of the two – an asteroid and volcanic eruptions – killed the dinosaurs: the impact accelerated the volcanism that was already happening on the other side of the world, producing even more lava and volcanic gases with perhaps more frequent or longer eruptions.

That study cited timing, as the impact at Chicxulub and the Deccan Traps eruptions happened quite close to the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, as geologists call the moment when all non-avian dinosaurs and many other living species vanished.

But this new study, based on numerical modeling simulating the environmental impacts of sulphur gas emissions, suggests the volcanism may have made it harder for the animals to recover from the asteroid impact, if that was indeed the extinction trigger.

“The sulphur alone cannot explain the extinction of the dinosaurs, says Schmidt. “The volcanism could have had some small role, but on its own, the sulphur can’t explain the mass extinction.”

“If you take the two studies together, there’s a good argument for volcanologists to better understand how long these eruptions lasted, how much lava was produced, how long were the periods of non-activity. And then you can better understand whether the volcanism might have indeed suppressed the recovery a little bit, which is quite different from causing an extinction,” Schmidt says.

Black adds, “This study tells us is that if the Deccan Traps did play a major role in the extinction that killed the dinosaurs, we still don’t quite understand how that might have worked because the study points towards selective stresses from sulphur and it’s not clear, from their results, how sulphur alone might have been sufficient to cause the mass extinction that we observe.”

Many questions still remain about the timing and environmental impacts of both events.

Regardless of whether or not the volcanism caused a global mass extinction itself, it still was likely a massive event.

“Set aside the question about mass extinctions altogether for a moment and then just try and imagine the eruptions that the study is considering. They are still extraordinary events. If you imagine witnessing the eruptions and their aftermath in terms of temporary cooling and sulphur aerosols in the sky, it would have been really a spectacular thing to see,” says Black.

Schmidt adds, “Volcanic eruptions are really spectacular and it’s a force of nature that humans have no control of.”