Tyrannosaurus rex had competition for biggest bite

Loading...

Advances in digital imaging have led to exciting discoveries about what goes on inside the skulls of living things. But what about creatures long extinct?

Researchers from England's University of Bristol have found that the famed Tyrannosaurus rex had some competition for the fiercest bite. The lesser known, but equally ferocious Allosaurus fragilis proved to be the biggest mouth chasing its prey in the Jurassic Age, a conclusion reached through careful study of digital imaging and computer analyses.

The study, which was published Wednesday in the Royal Society Open Science, examined three species, carnivores Allosaurus fragilis, T. rex, and the vegetarian Erlikosaurus andrewsi. All three are grouped into the category of two-legged dinosaurs called theropods. Understanding the measurements of the dinosaurs' main mechanism for eating means future researchers can establish niche adaptations for each species, and more accurately speculate about eating habits and hunting behaviors.

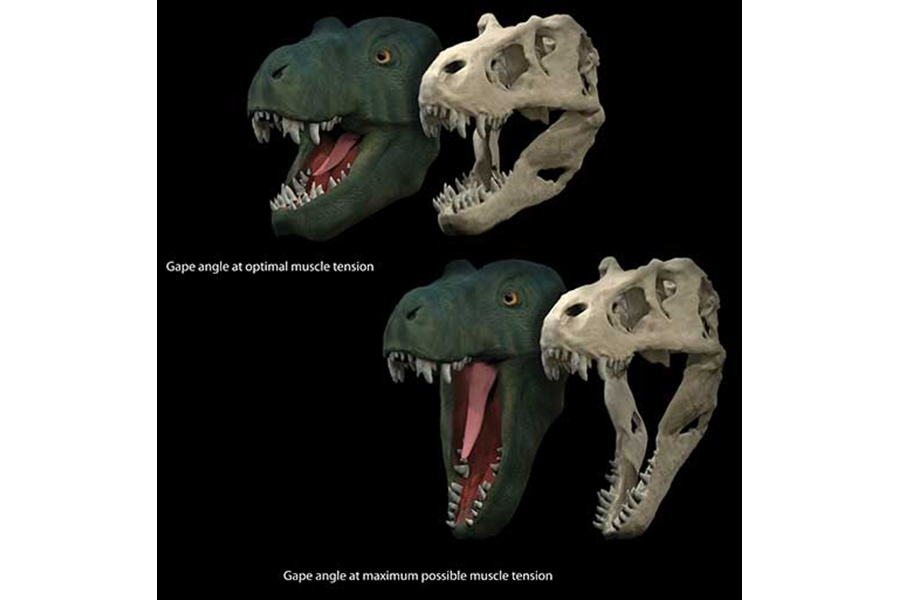

By looking at the dinosaurs' jaw musculature, the researchers found that the Allosaurus - a massive-headed, short-armed, meat-eater - was able to open its jaws wider than a right angle, between 79 and 92 degrees. Its maximum jaw gape was larger than Tyrannosaurus rex, a bigger carnivore - though with similar features - that roamed North America about 66 million years ago. T. rex was able to open its jaws a slighter, but still fearsome, 63.5 and 80 degrees.

"Swift ambush predators such as Allosaurus had the largest jaw gape among the studied dinosaur species, which is consistent with the requirement for a predator hunting larger prey," Bristol paleontologist Stephan Lautenschlager, told Reuters.

"Tyrannosaurus, in comparison, was able to exert continuous muscle force during different gape angles, which would be necessary for an animal biting through thick flesh and crushing bones."

Erlikosaurus, the herbivore, was a gawky creature by comparison, with a long neck, convex belly, and short arms that ended in three long claws. It topped out at about 20 feet long, and roamed Central Asia about 90 million years ago. In contrast to the hulking carnivores, its maximum jaw gape was measured at about half, reaching 43.5 to 49 degrees.

Dr. Lautenschlager said Allosaurus and T. rex likely relied on their maximum jaw gape only rarely, "probably only in cases when large prey had to be captured." Their mouths were probably more comfortable in the "optimal" range of 28 degrees.

For the study, which was published Wednesday in the journal Royal Society Open Science, Lautenschlager constructed digital models based on scans of skull fossils, with jaw muscles reconstructed based on features detectable on the bones where muscles were once used for stalking, capturing, and devouring.

Understanding jaw gape provides further insight into the mysterious lives of dinosaurs, and helps us better understand who could eat what, and how, Lautenschlager said.

This report contains material from Reuters.