In an ancient sci-fi scenario, 290-million-year-old animals regrew limbs

Loading...

Regrown limbs sounds like a creepy scenario from a science fiction movie, but for salamanders it is reality.

And they're not alone. Now researchers found that limb regeneration has origins deep in the history of life on Earth.

Fossilized four-limbed animals from some 290 million years ago also display signs of limb regeneration, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature.

These ancient specimens suggest that regeneration was more widespread among ancient four-limbed vertebrates, known as tetrapods, at the time than it is in modern ones.

“By looking at some of these extinct organisms, we’ve been able to figure out that this ability to regenerate is actually very old and is much more common among animals than we thought,” study co-author Jennifer Olori, a vertebrate paleontologist at SUNY Oswego, tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview.

“Until our work, it was really only known to be, the amazing powers of limb regeneration, in salamanders and a little bit of regenerative properties in lizards and also a little bit in frogs and in lungfishes, but not to the degree that we see in salamanders,” says Dr. Olori.

Lizards, for example, can regenerate their tails, but the new tails lack the same skeletal properties as the original tail. Instead, she explains, they just produce some featureless cartilage. But salamanders can regrow a new limb with all the same bones, muscles, and nerves.

Sometimes those new salamander legs don’t grow back perfectly, or a “finger” isn’t quite the same.

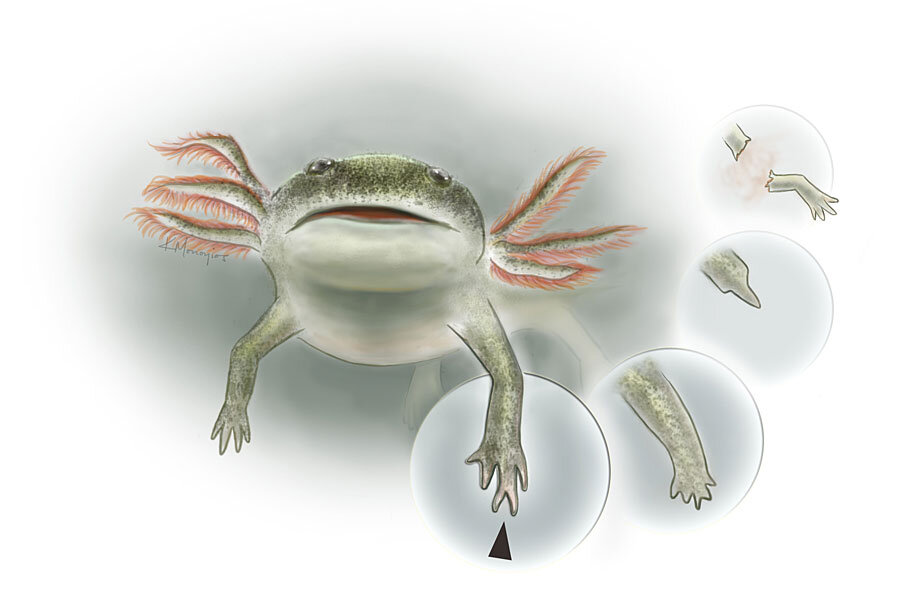

The researchers found similar digit abnormalities in fossils of ancestors of modern salamanders, suggesting that they, too, had this peculiar regeneration ability.

“We saw some similar patterns that we see in living things when they regenerate, like having parts of the limb that lag behind or move ahead of other parts of the limb in terms of their development,” says Olori.

“The upper part of the arm might be very well developed, for example, and the lower part of the arm be less developed, showing that there’s sort of a difference in timing there and that part of it may have regenerated,” she says.

Or perhaps a tail might be caught in regeneration, with some vertebrae well formed, while others were still in the formation stages, Olori says.

What's more, it wasn’t only salamander’s ancestors that had this ability. Some of these extinct tetrapods were actually more closely related to reptiles and mammals than to amphibians.

Knowing that, Olori says, “We can infer that this is an inherited trait that they actually got from their common ancestor a very long time ago, hundreds of millions of years ago.”

So the fossils these researchers examined may not have been among the first animals to undergo limb regeneration. The ability may be much older than 290 million years.

“We’ve put forth a new hypothesis about where regeneration might have originated, suggesting that it’s really old and very common,” says Olori.