Japan's big earthquake: Why deeper means safer

Loading...

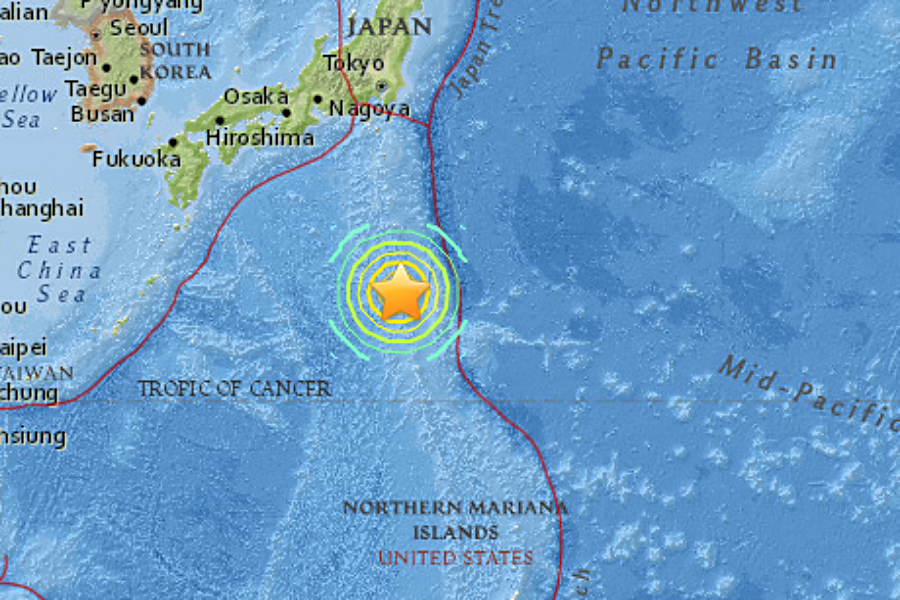

A major earthquake – magnitude 8.5, says the Japan Meteorological Agency – struck off the coast of Japan Saturday.

The temblor was felt throughout the country, knocking dish and a few people over, but there were no reports of deaths or major damage.

How could such a large magnitude quake cause so little damage and no serious injuries?

The answer lies far below the surface of the Earth.

Saturday's quake was a deep one, 590 kilometers (370 miles) below the surface, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency. The US Geological Survey reported it as a magnitude 7.8 quake located 678 kilometers (421 miles) below the surface.

The USGS categorizes earthquakes as shallow (up to 70 kilometers or 43 miles), intermediate (70-300 kilometers or 43-186 miles) or deep (186-434 miles). That puts Saturday's quake near the bottom of the Earth's crust.

Generally speaking, the deeper the quake, the less violent and less dangerous. That's because the strength of shaking - or energy released - felt from an earthquake diminishes with increasing distance from the quake's source.

When judging the potential impact on lives and property, both earthquake magnitude and depth must be taken into consideration.

For example, the April 2015 Nepal earthquake was just 9 miles below the ground, and killed an estimated 8,800 people.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake that killed more than 100,000 people had a magnitude of 7.0 (much less than Saturday's Japan quake) but it was very shallow, just 13 kilometers (8 miles) below the surface.

Also, the 1994 Northridge, Calif., earthquake registered a magnitude of 6.7 but started at a depth of about 18 km (12 miles) and ruptured up to a depth of 5 km (3 miles). It caused damaged estimated to be between $20 billion and $40 billion and killed about 60 people, the USGS reports.

Moreover, there's evidence that suggests deep earthquakes are more efficient in dissipating stress than shallow ones, according to scientists who investigated a May 2013 a magnitude-8.3 earthquake that struck beneath the Sea of Okhotsk, between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula and Japan.

The researchers added, according LiveScience.com, that this 2013 "deep quake may have been good at releasing energy quickly because it ruptured within a very old rock. The northwest Pacific crust that is subducting in this area is some of the oldest, coldest oceanic crust subducting on Earth. Its age means it is brittle, enriched with concentrations of stress that enlarge the rupture zone and can easily be triggered, greatly shortening the delay between aftershocks."

While deep quakes may be less dangerous, they tend to be felt by more people, explains the USGS.

Large deep-focus earthquakes may be felt at great distance from their epicenters. The largest recorded deep-focus earthquake was a 2013 M 8.3 earthquake that occurred at a depth of 600 km within the subducted Pacific plate beneath the Sea of Okhotsk, offshore northeastern Russia. The M 8.3 Okhotsk earthquake was felt all over Asia, as far away as Moscow, and across the Pacific along the western seaboard of the United States. ...

Over the past century, 66 earthquakes with a magnitude of M7 or more have occurred at depths greater than 500 km; three of these were located in the same region as today's event.

Deep quakes are more rare than shallow quakes. Only about 3 percent of total energy released by temblors comes from deep earthquakes, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. More common are the shallow quakes which produce about 85 percent of the total energy released by the earth's shifting crusts.

How is earthquake depth determined?

Geologists rely on seismic measuring stations which measure the interval between the arrival of the primary (P) and secondary (S) waves. The difference between the P and S waves is used to measure the distance of the earthquake from the sensor.

Here's how the USGS describes the process for finding a quake's depth:

The most obvious indication on a seismogram that a large earthquake has a deep focus is the small amplitude, or height, of the recorded surface waves and the uncomplicated character of the P and S waves. Although the surface-wave pattern does generally indicate that an earthquake is either shallow or may have some depth, the most accurate method of determining the focal depth of an earthquake is to read a depth phase recorded on the seismogram. The depth phase is the characteristic phase pP-a P wave reflected from the surface of the Earth at a point relatively near the hypocenter. At distant seismograph stations, the pP follows the P wave by a time interval that changes slowly with distance but rapidly with depth. This time interval, pP-P (pP minus P), is used to compute depth-of-focus tables. Using the time difference of pP-P as read from the seismogram and the distance between the epicenter and the seismograph station, the depth of the earthquake can be determined from published travel-time curves or depth tables.