Our apelike ancestors' hands were surprisingly like ours, say scientists

Loading...

The ancestors of humans may have evolved humanlike hands that were precise and powerful enough to use stone tools more than a half million years before such tools were even developed, researchers say.

A key trait that distinguishes modern humans from all other species alive today is the ability to make complex tools. This capability depends not only on the extraordinarily powerful human brain, but also the strength and dexterity of the human hand.

In new research, the scientists looked at a major factor behind the power and precision of the human grip, which is the structure of the metacarpals, the bones in the palm. For instance, the third metacarpal, which connects the middle finger to the wrist bones, includes a little projection of bone called a styloid process that helps it lock into the wrist. This helps the fingers apply greater amounts of pressure to the wrist and palm than it would otherwise, for a stronger grip.

"The styloid process is one of the key features of a suite of morphological characteristics of the human hand that is linked to forceful use of the thumb during tool use," said study co-author Tracy Kivell, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Kent in England.

Previous research has suggested that this styloid process was found only in members of the human lineage, which all belong to the genus Homo. The earlier direct ancestors of the human lineage were probably the australopiths, members of the genus Australopithecus, who "did not have a styloid process, or several of the other features that are common in human hands," Kivell told Live Science. [Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special]

Now, Kivell and her colleagues have found evidence suggesting that australopith hands were nevertheless capable of powerful and precise grips.

The scientists investigated the bones of a number of hominins — the group of species that had split from the chimpanzee lineage, and consists of humans and their relatives. They focused on fossils from Australopithecus africanus that date back 2 million to 3 million years ago, as well as hominin bones from South Africa from the Pleistocene Epoch, that date to 1.8 million to 1.9 million years ago.

The researchers studied the fine mesh network of bone within the metacarpals known as trabeculae. The density and orientation of trabeculae in the metacarpals depend on how the hands are used. Researchers can tell by looking at the trabeculae, for example, if the hands were used to climb in trees or to grip objects in modern humanlike ways. In modern times, human metacarpals are less dense in trabeculae than those of chimps and gorillas, probably because humans rarely use their hands to support their bodies during locomotion as apes do.

The scientists found that Australopithecus africanus and the other South African hominin fossils they analyzed possessed humanlike trabecular patterns in their metacarpals. This suggests that these species gripped their fingers and thumb together in ways typically seen during tool use.

"We are suggesting that even without the full suite of humanlike morphology, early hominins were capable of forceful precision and power grips," Kivell said.

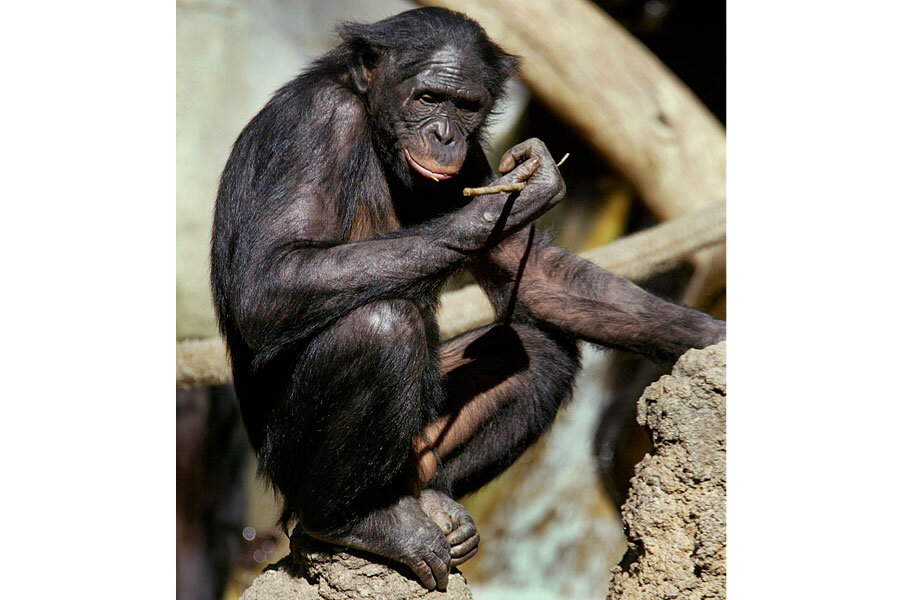

The ability to make and use tools dates back millions of years in the human family tree. Chimpanzees, the closest living relatives of humans, can on their own devise spearlike weapons for hunting, suggesting the ability to use wooden tools dates back at least to the time when the ancestors of humans and chimps diverged, some 4 million to 7 million years ago.

But the first stone tools do not appear in the archaeological record until about 2.6 million years ago in Ethiopia. The new findings suggest australopiths may have had the capacity to handle stone tools more than a half million years before such tools were developed.

Aside from tool use, the findings suggest that australopiths had forceful precision grips that "could have been used for other manipulative behaviors, like food gathering, food processing, or use of wood or plant tools that would not preserve in the fossil record," Kivell said.

Scientists remain uncertain how powerful or precise australopith grips were. "It's likely they were not as dextrous as humans, but exactly what kind of ability or how often they used it, we cannot say," Kivell said.

The scientists plan to study the relatively complete fossil hand of Australopithecus sediba, which some researchers suggest may be the immediate ancestor of the human lineage.

"Relatively complete hands are extremely rare in the early hominin fossil record, so an analysis ofAustralopithecus sediba will allow us to look at more bones and hopefully say more about overall hand function and use," Kivell said.

The scientists detailed their findings in tomorrow's (Jan. 23) issue of the journal Science.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

- The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body

- 8 Humanlike Behaviors of Primates

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.