First results from NASA's MAVEN may offer clues to how Mars lost its water

Loading...

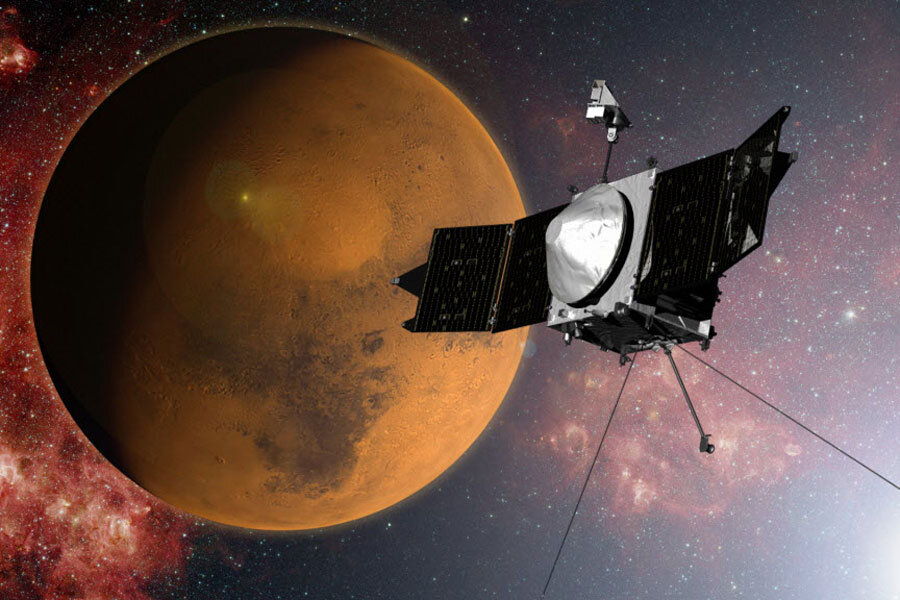

NASA's MAVEN orbiter is beginning to help planetary scientists unravel the mystery of Mars' missing water – once abundant on the red planet early in its history, but now long gone, mainly lost to space over billions of years.

Evidence is mounting that during that early, wet period, Mars hosted conditions that were hospitable to microbial life, although so far no clear evidence has emerged that life ever gained a foothold there. That's a far cry from the dry, desolate planet astronomers see today.

Two general observations that predate MAVEN lend credence to the idea that the planet lost its water to space, researchers say.

One is the apparent dearth of large deposits of minerals that formed in water (think Britain's White Cliffs of Dover). So Mars itself didn't soak up much over time.

The second comes courtesy of NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. It has measured the relative abundance of two forms of argon in the atmosphere from the floor of Gale Crater, where the rover currently is operating. One form of argon is heavier than the other. The heavier form, or isotope of argon, dominates, suggesting that the lighter ones escaped to the upper atmosphere to be swept away via the sun's solar wind.

In the case of water, over time interactions with ultraviolet light from the sun and with charged particles streaming from the sun as solar wind are thought to have split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen at high altitudes. As such splits took place, the solar wind would absconding with the lighter hydrogen, leaving the heavier oxygen behind.

But until MAVEN, which arrived at the red planet in September, no craft has explored the region of Mars' atmosphere where such losses are thought to have taken place.

Now, MAVEN instruments have returned data highlighting two key processes that could have played a role, according to scientists presenting their results Monday at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, currently underway in San Francisco.

Using the craft's Suprathermal and Thermal Ion Composition (STATIC) instrument, researchers have made their first map of the effect temperature has on ions at different altitudes in the upper atmosphere. The temperature rises with altitude, boosting the speed of flitting ions until they reach levels that allow them to escape Mars's gravity. Once free, they can accelerate to very high energies as they move away from the planet, explained the University of California at Berkeley's Jim McFadden, STATIC's lead scientist.

The STATIC team's initial results looked at acceleration of atomic and molecular oxygen, helium, and hydrogen at four altitudes in the ionosphere. These heights ranged from 155 miles up to 500 miles up. At 155 miles the ions are less than -100 degrees C, or about 150 degrees below zero F. By 180 miles up, hydrogen ions begin to wake up, becoming more energetic relative to heavier atoms and molecules. At 250 miles up, hydrogen ions are moving fast enough to leave the planet.

As they reach 300 miles up, they continue to gain energy with altitude, reaching about 10,000 times the energy they started with.

Eventually some of the heavier ions can achieve energies of more than a million times the energy they started with, Dr. McFadden explained. This leaves Mars with a flowing mohawk of ions streaming spaceward, he adds.

Mars's upper atmosphere and ionosphere presented the MAVEN team with a surprise: The ionosphere apparently doesn't deflect the solar wind, as previously thought. Protons – essentially hydrogen ions – from the sun hit the upper atmosphere, take on an electrically neutral form, then pass through the ionosphere. Once through, they become ions again.

At the moment, it's unclear what role this might have played in the mystery of vanishing water on Mars. But it provides researchers with an immediate boon, noted Jasper Halekas, a University of Iowa researcher who heads the team using another instrument on MAVEN, the Solar Wind Ion Analyzer.

Ideally, MAVEN should be making several measurements simultaneously as its orbit repeatedly takes it deep into Mars's ionosphere and back out. But researchers were concerned that the craft would have no way of measuring what was going on with the solar wind during MAVEN's "deep dip" excursions into the ionosphere – important for understanding the wind's effect on that atmospheric layer.

This new discovery about the interactions between the solar wind and upper atmosphere means those simultaneous measurements will be possible. Dr. Halekas said.