What can a robot learn from a flightless bird? Lots, it turns out.

Loading...

Picture a robot version of the Road Runner.

That's what researchers at Oregon State University are aiming for, and they've found that the best real-life models for running robots may be birds. The research team worked with scientists from the Royal Veterinary College, studied the movements of ground-running bird species and uncovered why these not-so-graceful bipeds are impressively efficient when darting from one place to another.

Scientists already understood the basic locomotion of legged animals: the larger an animal gets, the more it tends to run with straighter legs in an attempt to compensate for the increased demand for lower body strength. By contrast, smaller animals tend to crouch more.

Researchers thought that in the case of birds, this scaling effect for posture would also be the case for navigation strategies on uneven terrain. The more compact ones would be better equipped to handle disturbances in their running paths, they reasoned, because their crouched postures would naturally prioritize stability. Bigger birds would focus less on stability and more on keeping internal forces low to ease stress on leg muscles.

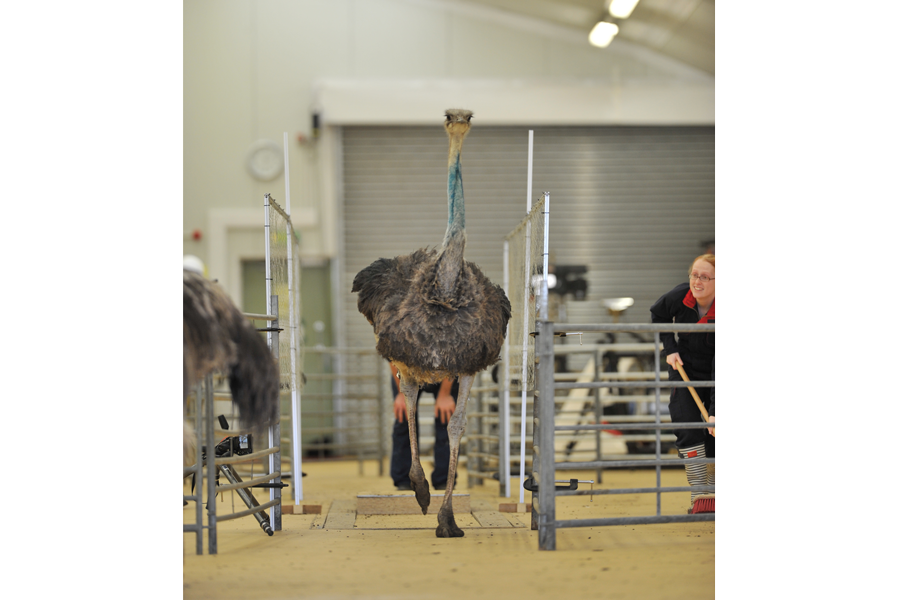

The researchers looked at five different species of birds, including bobwhite quails, turkeys, and ostriches. From there, they developed computer models that replicated the behavior of the winged bipeds and found that their hypothesis was incorrect. Despite the large variations in the birds’ body shapes and sizes, their running methods were all quite similar.

"This is a big deal, because it means we've discovered something that is fundamental," Jonathan Hurst, OSU Associate Professor, told the Monitor.

The research group thought that body stability – in the way that we typically define the word – would be a top priority for these birds, but it turned out that this wasn't the case. While they did find that remaining upright is pertinent to their running, they saw that the birds allow their bodies to jostle a bit when sprinting, hence their looking somewhat gawky to humans. This apparent lack of coordination turns out to be quite functional.

"They aim not to fall,” says Dr. Hurst. “They aim to limit the peak forces in their muscles and legs - avoid injury.”

And, according to Hurst, it's okay if their upper bodies lurch here and there in the process.

Hurst and his colleagues found that this universal behavior among ground-running birds consists of about 70 percent vaulting and 30 percent crouching. This combination helps to minimize energy costs and reduce the likelihood a bird will hurt itself.

Scientists have typically built robots with an emphasis on a stable gait. But now with an understanding that more unsteady movements can actually be more energy efficient, Hurst and his team, which includes co-author and OSU doctoral student Christian Hubicki, can attempt to replicate the birds' movements in running robots.

"We should ultimately be able to encode this understanding into legged robots so the robots can run with more speed and agility in rugged terrain," Hubicki said in a release.

The range of possible applications for running robots with ostrich-like abilities is wide: from search-and-rescue missions in burning buildings to powered prosthetics for amputees.

Because all birds are descended from dinosaurs, these land-loving birds may have been evolving their running gaits for a few hundred million years. And it is something quite natural for these birds that scientists will now use to set a new standard for future robot design: a more relaxed definition of stability.

"What they are accomplishing is really quite elegant," said Hurst in a release.

The study’s findings were published last week in the journal Experimental Biology.