Tiny cube satellite launched by hand: Nano, nano?

Loading...

| Cape Canaveral, Fla.

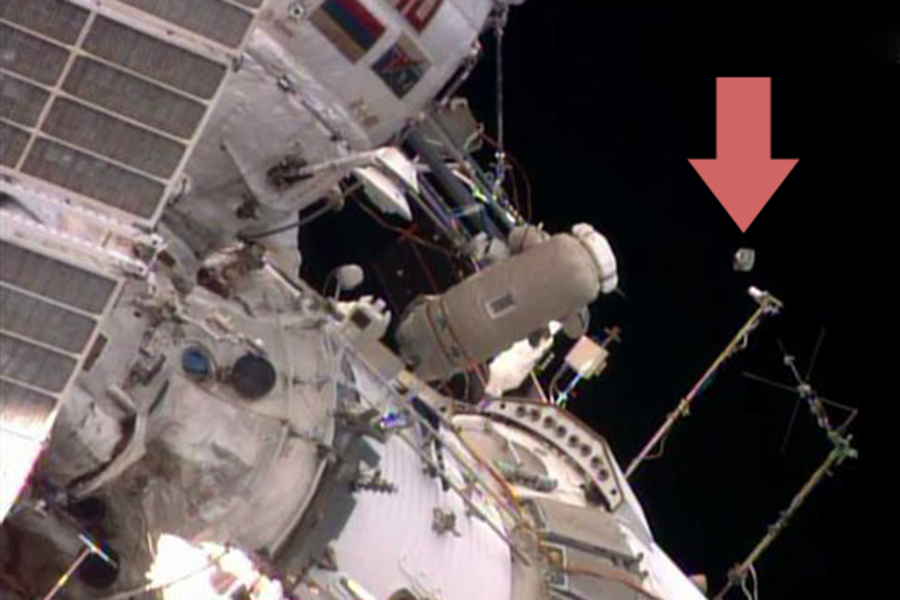

Spacewalking astronauts launched a tiny Peruvian research satellite Monday, setting it loose on a mission to observe Earth.

Russian Oleg Artemiev cast the 4-inch box off with his gloved right hand as the International Space Station sailed 260 miles above the cloud-flecked planet. The nanosatellite gently tumbled as it cleared the vicinity of the orbiting complex, precisely as planned.

"One, two, three," someone called out in Russian as Artemiev let go of the satellite.

Cameras watched as the nanosatellite — named Chasqui after the Inca messengers who were fleet of foot — increased its distance and grew smaller. Artemiev's Russian spacewalking partner, Alexander Skvortsov, tried to keep his helmet camera aimed at the satellite as it floated away.

The satellite — barely 2 pounds — holds instruments to measure temperature and pressure and cameras that will photograph Earth. It's a technological learning experience for the National University of Engineering in Lima. A Russian cargo ship delivered the device earlier this year.

Less than a half-hour into the spacewalk, the satellite was on its way, flying freely.

NASA has launched more than 30 CubeSats in recent years, mostly as low-cost experiments for universities.

The CubeSat Launch Initiative (CSLI) enables the launch of CubeSat projects designed,built and operated by students, teachers and faculty to obtain hands-on flight hardware development experience. CSLI also provides access to space for CubeSats developed by theU.S. government and non-profit organizations giving all these CubeSat developers access to a low-cost pathway to conduct research inthe areas of science, exploration, technology development, education or operations. Since its inception in 2010, the initiative has selected more than 100 CubeSats from primarily educational and government institutions across the United States.

With that completed, Artemiev and Skvortsov set about installing fresh science experiments outside the Russian portion of the space station and retrieving old ones. "Be careful," Russian Mission Control outside Moscow warned as the astronauts made their way to their next work site.

The two conducted a spacewalk in June, a few months after moving into the space station. Four other men live there: another Russian, two Americans and one German.

U.S. spacewalks, meanwhile, remain on hold.

NASA hoped to resume spacewalks this month after a yearlong investigation but delayed the activity until fall to get fresh spacesuit batteries on board. The SpaceX company will deliver the batteries on a Dragon supply ship next month. Engineers are concerned about the fuses of the on-board batteries.

Before the battery issue, NASA was stymied by a spacesuit problem that nearly cost an Italian astronaut his life last summer. Luca Parmitano's helmet flooded with water from the suit's cooling system, and he barely made it back inside. The investigation into that incident is now complete, with safety improvements made to the U.S. spacesuits.

___

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material