Milky Way's black hole eats gas the same way Cookie Monster eats cookies, research shows

Loading...

The colossal black hole at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy is a messy eater. Of all the gas that falls toward the black hole, 99 percent gets spewed back out into space, new observations show, making the black hole akin to a toddler whose food ends up mostly on the floor, rather than his mouth.

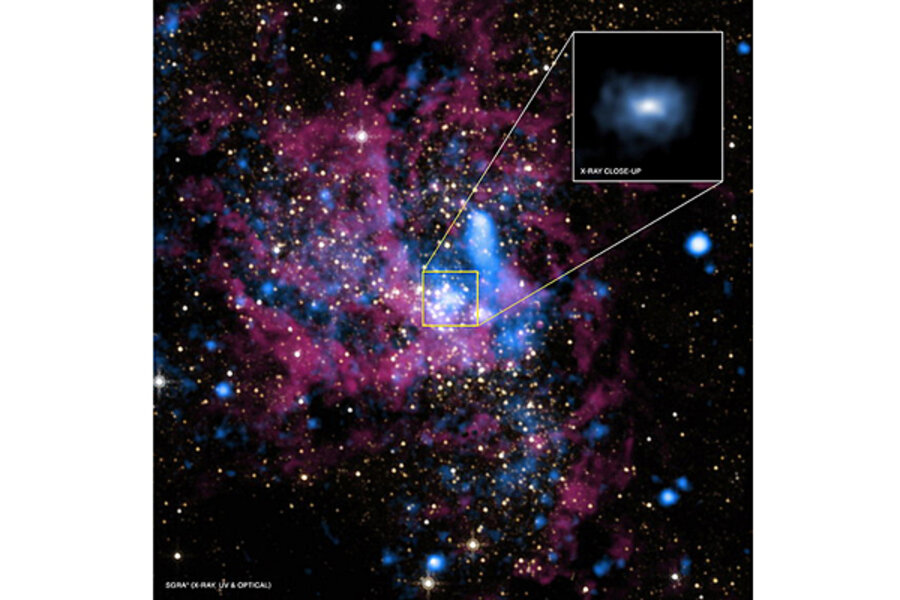

The Milky Way's supermassive black hole, called Sagittarius A* (pronounced "Sagittarius A-star"), contains the mass of 4 million suns. Yet it's not getting much larger, according to the new findings, which help explain why the object is surprisingly dim.

Although black holes themselves can't be seen, their immediate vicinities usually emit strong radiation from the material falling into them. Not so for Sgr A*, though, which has prompted a rash of competing theories trying to explain its surprising lack of light. [Strangest Black Holes In the Universe]

"There's been a debate for the last 20 years or so about what actually is happening to the matter around the black hole," said research leader Q. Daniel Wang of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. "Whether the black hole is accreting the matter, or actually whether the matter can be ejected. This is the first direct evidence for outlflow in the accretion process."

The new findings show definitively that most of the matter in the gas cloud surrounding the black hole is ejected out into space, which explains why it doesn't release light on its way in to be eaten.

3 million seconds

The discovery comes via new observations taken by NASA's Chandra X-Ray Observatory that required the equivalent of about five weeks of observing time (Wang gave the amount of time as 3 megaseconds, or 3 million seconds), spread out over months, to achieve unparalleled resolution of the area around Sagittarius A*.

The X-ray views focused on the cloud of hot gas surrounding the black hole, and found that there was much less higher-temperature gas than lower-temperature gas there. Because mass heats up as it falls toward a black hole, the researchers were able to infer that gas was being lost during this process. "There must be ejection of matter when the gas is moving in," Wang explained.

"Exactly how it happens is not totally clear," Wang told SPACE.com. "There are all kinds of simulations and theories which predict that it should occur. But this is the first observational evidence that can say this does occur."

Scientists still have a ways to go to see the area in enough detail to decipher the mechanism for the gas ejection, he said. They also don't yet know where all this gas goes, he added.

Ruled out theories

The new observations definitively rule out some theories that had attempted to explain the perplexing dimness of Sgr A*, such as one idea that most of the light there was being emitted by a potential group of rapidly rotating low-mass stars.

Wang and his colleagues' findings are detailed in the Aug. 30 issue of the journal Science.

"This result is important not only for Sgr A*, but also all other

low-luminosity black holes, since we now have a better understanding of

their radiative efficiency, i.e., how to relate the light that we see to

the amount of gas actually getting accreted onto the black hole," astrophysicist Jeremy Schnittman of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., wrote in an email. Schnittman was not involved in the research, but wrote a commentary article on the findings published in the same issue of Science.

The new data also offer some evidence for where the gas cloud comes from. The Chandra observations show its shape in better detail than ever before, and suggest that it closely mirrors the distribution of a group of massive stars previously seen there, which have formed a disc. Massive stars are known to emit strong winds of material that fly out at superfast speeds. Wind from these stars is likely colliding, producing the hot plasma of gas found around the black hole, Wang said.

Many of the researchers ideas about Sagittarius A* can be further tested in the coming months when a rare event occurs. A small cloud of gas is on a collision course with the black hole, and is due to be gobbled up before scientists' eyes. Because this cloud is made of cold and not hot gas, it's expected to be almost fully consumed by Sagittarius A*.

"It will be really interesting to see what happens when the G2 cloud approaches later this year," Schnittman told SPACE.com in an email. "Will the efficiency change when the accretion rate goes up? Is there an abrupt transition to a new type of accretion? Will we see anything different at all?"

Stay tuned!

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

- Images: Black Holes of the Universe

- No Escape: Dive Into a Black Hole (Infographic)

- Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.