Elon Musk unveils Hyperloop plan. How would it work?

Loading...

A trip from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 35 minutes for $20 one way? That's the latest vision from Internet, aerospace, and automotive entrepreneur Elon Musk, who on Monday unveiled his Hyperloop concept for the 350-mile commute.

What's a Hyperloop? Think of a physicist's linear accelerator, but for passenger pods rather than protons – and, if all goes well, without the collisions.

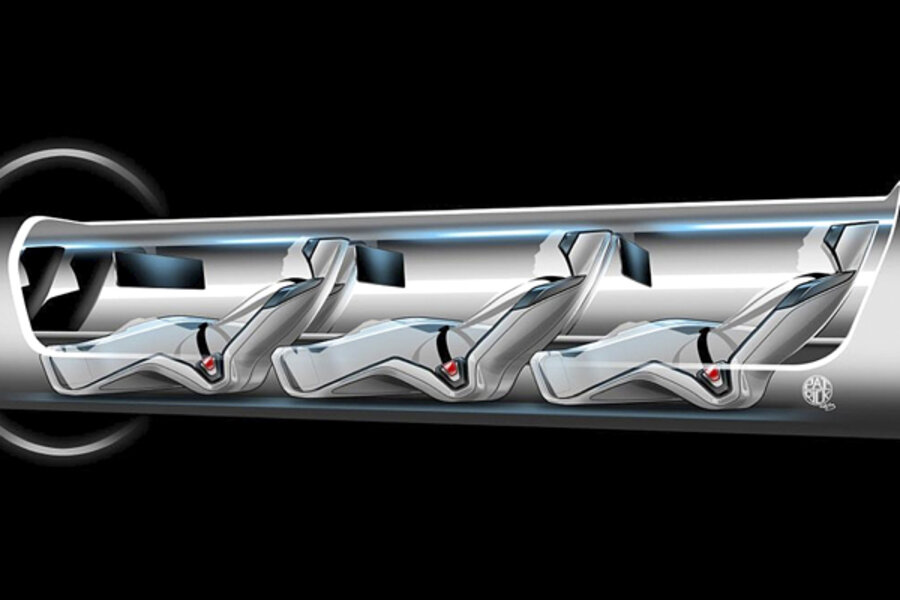

As sketched out in a 57-page white paper, pods carrying 28 passengers each would leave the station at two-minute intervals. Travel speeds would average 540 miles an hour, peaking at 760 m.p.h. along part of the route.

Energy to power the system would come courtesy of solar panels atop the elevated tubes.

The system could be built for about $6 billion – or somewhat more if an operator wanted to turn the Hyperloop into a high-speed version of Amtrak's Auto Train, which allows passengers to take cars or motorcycles with them, Mr. Musk and his technical team from Tesla Motors and Space Exploration Technologies estimate.

And it would be expandable to achieve many of the same transportation aims that California's high-speed rail project is intended to reach.

Musk knows the commute well, reportedly shuttling by air twice each week between SpaceX in Hawthorne, near L.A. International Airport, and Tesla Motors headquarters in Palo Alto, Calif.

The concept was borne of Musk's frustration with California's plans for bullet-train service, which he argues would be slower, less safe, and, if unsubsidized, more expensive than flying. Given the enormous intellectual horsepower in places like Silicon Valley and Pasadena, home to Caltech and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he argues, California could have devised an approach that represents a less expensive, more weather-resistant, and more environmentally sustainable way to operate.

Others have proposed variations on Musk's Hyperloop. Some envisioned capsules hurtling through an oversize pneumatic tube – the main delivery system for documents in office buildings in the days before e-mail. Others have proposed running capsules through a tube void of any air, which would eliminate air resistance and allow passenger capsules to reach high speeds. But each comes with its own set of engineering and safety challenges.

The Hyperloop splits the difference. To reduce air resistance as the aerodynamic capsule races through elevated steel tubes, air pressure would be reduced to levels equivalent to flying at 150,000 feet, while air pressure inside the capsules would be kept at normal levels – a concept familiar to anyone flying in commercial airliners.

The system relies on linear motors some 2.5 miles long to accelerate the capsules to top speed, and then decelerate them, at the appropriate locations along the route.

The design leaves little room between the capsule and the tube walls for air to flow along the capsule's length, which would allow pressure to build up ahead of the capsule and introduce drag. To keep air moving, the capsule sports a compressor in front that operates much like the compressor in a jet engine. In this case, the compressed air flows out through exhaust ports to keep the capsule levitated and provide additional push.

The plan also includes a proposed route that would have less impact on the landscape, but more on the view, than a bullet train. And it indicates sections along the route that would require the capsules to slow a bit to perhaps 300 miles an hour to avoid exposing passengers to large G-forces as the capsules take curves.

The approach requires no exotic technologies, such as energy-hungry superconducting magnets. But it uses existing technologies in an outside-the-box combination.

During a press briefing Monday, Musk acknowledged that – unlike SpaceX or Tesla – he doesn't have the bandwidth to build the system. Instead, he suggested he might underwrite a demonstration project to test the concept's feasibility. After that, it's up to someone else to take the concept and run with it, he said.

That could be a tough proposition. California's high-speed rail project has left the station. In May, the California High Speed Rail Authority selected a lead contractor for the project, and it currently is in the market for contractors who can supply environmental and right-of-way engineering services.

For the benefits that might accrue to business travelers on the L.A. to 'Frisco run, the price tag that Musk estimated for his Hyperloop system could be put to better use, some suggest.

"Over the years there have been many proposals to reduce intercity trip times," notes Juan Matute, director of the Local Climate Change Initiative at the University of California at Los Angeles's Lewis Center, via e-mail. "Supersonic flight and high-speed rail are two ideas that came to fruition," if briefly, in the case of supersonic airliners.

But, he adds, "No proposal has obviated the need to improve transportation within cities and regions to give people greater reliability on the transportation networks they use every day."

Chicago to St. Louis, anyone?