Scientists implant false memories in mice

Loading...

“Memory is deceptive because it is colored by today’s events,” said Albert Einstein. It is also deceptive because it is frequently wrong, sometimes dangerously so.

Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed the ability to implant mice with false memories. The memories can be easily induced and are just as strong as real memories, physiological proof of something psychologists and lawyers have known for years.

The findings are a serious matter. According to the Innocence Project, eyewitness testimony played a role in 75 percent of guilty verdicts eventually overturned by DNA testing after people spent years in prison. Some prisoners may even have been executed due to false eyewitness testimony. It was not because the witnesses were lying. They were just wrong, said Susumu Tonegawa, a molecular biologist and the lead author in the MIT study.

In the longest criminal trial in American history, the McMartin family, who operated a preschool in California, was charged with multiple incidents of child abuse. After seven years and $15 million in prosecution expenses, some charges were dropped and the defendants were acquitted of others when it became clear some of the accusations were based on false memories, some possibly planted by childrens’ therapists.

There is now a False Memory Syndrome in scientific literature and a False Memory Syndrome Foundation.

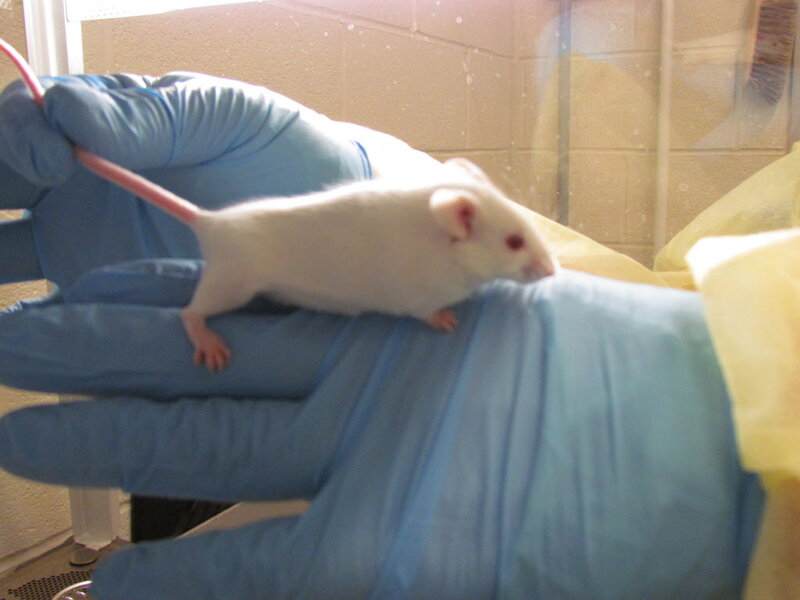

Last year, Tonegawa and his team published a study in Nature showing how false memories could be implanted in mice. They first put mice in a chamber -- the scientists called it the Red Room -- and let the animals roam around exploring so they could build up a contextual memory of it.

After a while, they gave the mice mild electric shocks to their feet and a blue light flashed in their brains delivered by a fiber-optic cable, implanting the memory that the Red Room was a dangerous place.

The next day researchers put the mice in an entirely different chamber – the Black Room – and let them explore peacefully. The mice were not afraid until the light flashed. The mice froze again although they were not in the chamber where they had received a shock. Why?

Memory is largely in the hippocampus, Tonegawa said, in a section called the dentate gyrus. Tonegawa, Steve Ramirez, a graduate student, and their colleagues identified the neurons there that were associated with experiential learning.

Events stimulate neurons when a memory is stored. Scientists discovered earlier that shining a blue light at the cells had the same result, activating the cells through a light-sensitive protein called ChR2. It’s called optogenetic manipulation because genes are involved in setting off the neurons.

Shining a blue light into the brains of the mice in the Black Room triggered the fear of being shocked as they had been in the Red Room.

“It demonstrated for the first time that activation of the neurons during formation of memory is sufficient for an animal to do everything needed to recall their memory,” Tonegawa said.

In a paper published this week in Science, the team went further.

Mice were let into the first chamber, and nothing happened. They acquired the memory of the environment and that it was safe. Then the scientists put the mice in a second chamber and sent a light into the brain, which would have triggered memories of the first chamber. Then came a mild shock.

The mice were placed back in the first chamber, where they had roamed safely before. The mice immediately ran to a corner and crouched. Knowledge of the context -- the safe environment of the first box -- was overpowered by the memory of the shock in the other chamber.

When the mice were put in a third chamber unlike the first two and were not given the light flash, they were unafraid. They were not reminded of their previous experiences, real or imagined.

The scientists had planted a false memory, and the mice believed it.

Tonegawa said people who remember falsely are not lying; they completely believe what they say. People with false memories are among those who can beat polygraph machines. Even when confronted by facts, such as DNA evidence, they refuse to believe their memories are wrong.

Elizabeth Loftus a cognitive psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, who has done more than almost anyone in attacking false and implanted memories in courtrooms and who has appeared as an expert witness in many trials, including the McMartin trial, said the finding was “very exciting.”

“It converges well with human data showing you can plant emotional memories into people’s minds,” she said.

Tonegawa, who won the Nobel Prize for Physiology in 1987, said there is a bright side to all this. Only humans have false memories; animals do not unless, like the mice at MIT, false memories are forced on them, he said.

“Humans are the most amazing, imaginative animals,” he said. “We are thinking. Lots of things are going on. Humans are recording what happens and passing it on.”

An imperfect memory, Tonegawa said, may be the price we pay for the imagination and creativity that makes us human.

Originally posted on Inside Science.