Scientists link rat brains via Internet

Loading...

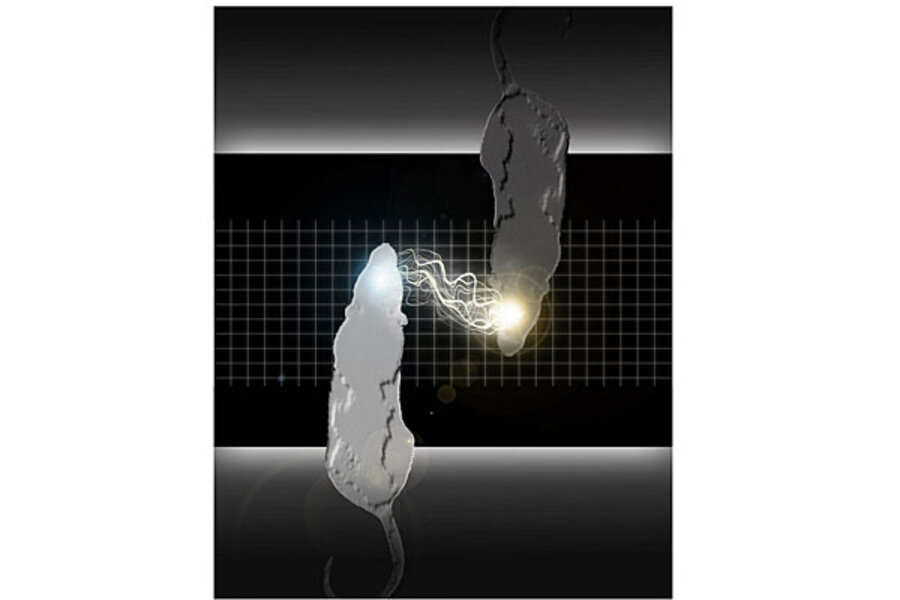

Scientists have engineered something close to a mind meld in a pair of lab rats, linking the animals' brains electronically so that they could work together to solve a puzzle. And this brain-to-brain connection stayed strong even when the rats were 2,000 miles apart.

The experiments were undertaken by Duke neurobiologist Miguel Nicolelis, who is best known for his work in making mind-controlled prosthetics.

"Our previous studies with brain-machine interfaces had convinced us that the brain was much more plastic than we had thought," Nicolelis explained. "In those experiments, the brain was able to adapt easily to accept input from devices outside the body and even learn how to process invisible infrared light generated by an artificial sensor. So, the question we asked was, if the brain could assimilate signals from artificial sensors, could it also assimilate information input from sensors from a different body?"

For the new experiments, Nicolelis and his colleagues trained pairs of rats to press a certain lever when a light went on in their cage. If they hit the right lever, they got a sip of water as a reward.

When one rat in the pair called the "encoder" performed this task, the pattern of its brain activity — something like a snapshot of its thought process — was translated into an electronic signal sent to the brain of its partner rat, the "decoder," in a separate enclosure. The light did not go off in the decoder's cage, so this animal had to crack the message from the encoder to know which lever to press to get the reward.

The decoder pressed the right lever 70 percent of the time, the researchers said.

The near mind merger was achieved with microelectrodes implanted in the part of the animals' cortex that processes motor information. And the brain-to-brain interface, which Nicolelis describes as an "organic computer," worked both ways: If the decoder chose the wrong lever, the encoder rat didn't get a full reward, which encouraged the two to work together. [Video - Watch the Brainy Rats Work Together]

"We saw that when the decoder rat committed an error, the encoder basically changed both its brain function and behavior to make it easier for its partner to get it right," Nicolelis explained in a statement. "The encoder improved the signal-to-noise ratio of its brain activity that represented the decision, so the signal became cleaner and easier to detect. And it made a quicker, cleaner decision to choose the correct lever to press. Invariably, when the encoder made those adaptations, the decoder got the right decision more often, so they both got a better reward."

The connection was not lost even when the signals were sent over the Internet and the rats placed on two different continents, 2,000 miles (3,219 kilometers) apart. The researchers say the results held true when the decoder rat was in a Duke lab in North Carolina and the encoder was with Nicolelis' colleagues at in Brazil, at the Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neuroscience of Natal (ELS-IINN).

The researchers are working on experiments to link the minds of more than two animals (this is something Nicolelis calls a "brain-net") to see if they could solve more complex problems cooperatively.

"We cannot even predict what kinds of emergent properties would appear when animals begin interacting as part of a brain-net," Nicolelis said. "In theory, you could imagine that a combination of brains could provide solutions that individual brains cannot achieve by themselves."

The research was detailed today (Feb. 28) in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- The 10 Weirdest Animal Discoveries of 2012

- Bionic Humans: Top 10 Technologies

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.