Look to a planet's mass, radius, and surface temperature for a first-cut answer. Radius and mass allow an estimate of density, which provides clues to the planet's bulk composition. Mass and radius also allow scientists to calculate the planet's escape velocity, the speed at which an object must travel to escape the planet's gravity.

Combine escape velocity with surface temperature and you glean a planet's ability to hold on to an atmosphere, which is a key factor in determining whether liquids exist on the planet. Estimates of the planet's surface temperature are based mostly on the planet's distance from its star and the star's surface temperature.

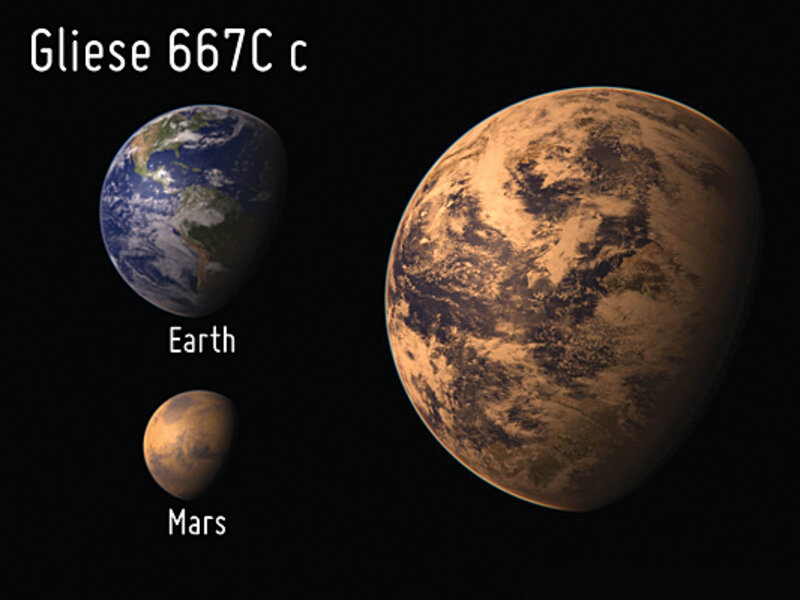

Using the rating system, scientists have labeled four confirmed exoplanets as similar to Earth. The most Earth-like are: Gliese 667Cc, followed by HD 85512b, Kepler 22b, and Gliese 581d. All are planets with masses larger than Earth's – so-called super Earths. (Kepler 22b could well fall off the list with additional data, says Abel Mendez, who heads the Planetary Habitability Laboratory at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo and is a member of the team that designed the rating system.)