How Lake Vostok could transform our understanding of life as we know it

Loading...

| Moscow

Russia said on Wednesday it had pierced through Antarctica's frozen crust to a vast, subglacial lake that has lain untouched for at least 14 million years hiding what scientists believe may be unknown organisms and clues to life on other planets.

Sealed deep under the ice sheet, Lake Vostok is one of the world's last unexplored frontiers. Scientists suspect its depths may reveal new life forms and a glimpse of the planet before the ice age.

If life is found in the lake's icy darkness, it may provide the best answer yet to whether life can exist in the extreme conditions on Mars or Jupiter's moon Europa.

"The 57th Russian Antarctic expedition has penetrated the waters of the subglacial Lake Vostok," Valery Lukin, head of the Russian Antarctic expedition, said in a statement.

After 20 years of stop-go drilling, the Russian team raced to chew through the final metres of ice and breached Lake Vostok in time to take the last flight out on Feb. 6 before the onset of Antarctica's harsh winter. It was here that the coldest temperature found on Earth, minus 89.2 Celsius (minus 128.6 Fahrenheit), was recorded.

Lukin said the breakthrough came on Feb. 5, on the eve of the mission's departure: "At a depth of 3,769 metres (12,365 ft) the drill bit made contact with the real body of water.

"The discovery of this lake is comparable to the first space flight in its technological complexity, its importance and its uniqueness," Lukin told Interfax.

But Russia must wait for the Antarctic summer to collect and study water samples, leaving the door open for U.S. and British missions to explore two other subglacial lakes and beat it to be the first to answer the question of whether life exists under the polar ice.

"We call it extraterrestrial life," Russian astrobiologist Sergei Bulat told Vesti 24 state television. "It will be useful to the search for life on other icy planets like Jupiter's satellite Europa."

Exploratory Rush

A century after the first expeditions to the South Pole, the discovery of Antarctica's hidden network of subglacial lakes via satellite imagery in the late 1990s set off a new exploratory fervour among scientists the world over.

"This is scientific exploration, this is work that no one has ever done before," Martin Siegert, head of the University of Edinburgh's School of Geosciences, told Reuters.

"This is probably one of the last frontiers on our planet that remains largely unknown to us," said Siegert, who is leading a British expedition to explore Lake Ellsworth in West Antarctica in 2012-2013.

Experts say the ice sheet acts like a blanket, trapping in the Earth's geothermal heat and preventing Antarctic lakes from freezing.

If there is life in Vostok and other ice-bound lakes, it is unlikely to be anything more complicated than single-cell organisms adapted to survive in the high-pressure, sunless environment, Siegert said.

"It is just imagination, we don't really know until we go in," he said.

Beneath the vast white landscape, Lake Vostok is the deepest and most isolated of Antarctica's subglacial lakes. Its size compares to Siberia's Lake Baikal or one of the Great Lakes, increasing the chance of biodiversity in its waters.

Scientists estimate the body of water is roughly 1 million years old and supersaturated with oxygen, resembling no other known environment on Earth.

John Priscu of Montana State University suspects that an oasis of life may lurk there, teeming around thermal vents.

"I hope that they can confirm unequivocally that there is indeed microbial life in the lake," said Priscu, the chief scientist on the U.S. project to probe subglacial Lake Whillans.

Alien Life

Russia has dreamed of uncovering the lake's secrets since the 1996 discovery that the low-lying buildings and radio towers of its Antarctic station sit above the ancient waters.

But the drive to explore this unspoilt environment is not without controversy.

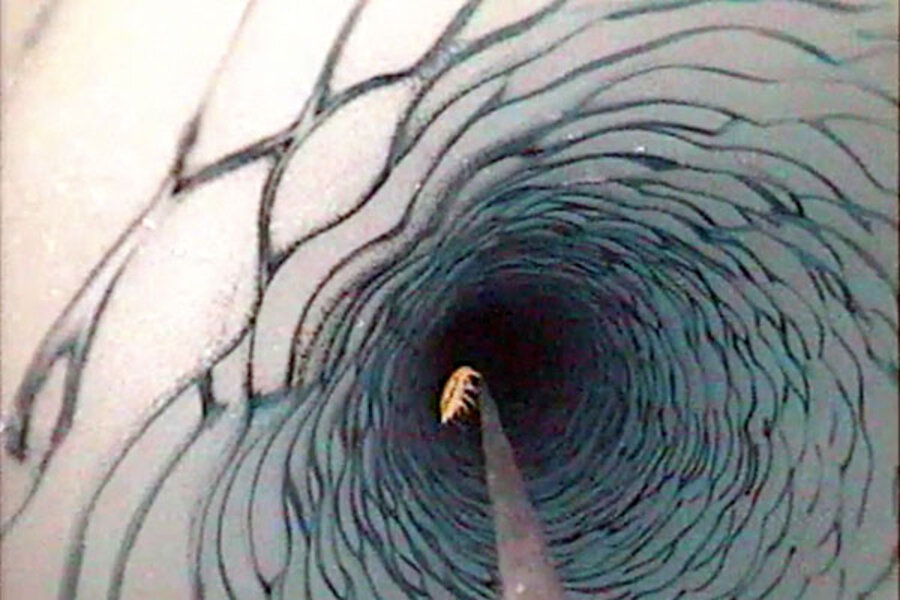

The Russian borehole, pumped full of kerosene and freon to keep it from freezing shut, hangs like a needle over the pristine lake. "The ice core at Vostok is there and it won't go away because it is full of anti-freeze," said Siegert.

In a bid to address international concerns, Russia halted drilling for several years to devise a cleaner method in 2000.

It used a smaller thermal drill to punch through to the lake and back pressured the borehole to force lake water to rise up into it, effectively sipping up samples from the lake's surface.

Russia will core out the frozen sample next season.

(Editing by Janet Lawrence)