Loading...

Why do Americans think more immigration means more crime? (audio)

There’s a nagging myth that immigration and crime go hand in hand, despite data to the contrary. Our reporters look at why the misperception endures.

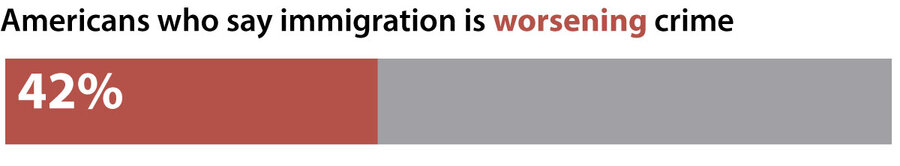

The findings, over decades, are clear: Immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than native-born Americans. Yet 42% of Americans still say immigration is making crime worse in the United States, according to a 2019 Gallup Poll.

“It’s very frustrating, because as much data as we have, the gap between perception and reality stays pretty firmly established,” says Charis Kubrin, a professor at the University of California, Irvine.

In this episode of “Perception Gaps: Locked Up,” our reporters explore the myth of “the dangerous immigrant,” the policies the stereotype has produced, and the impact our assumptions have on the institutions we build.

Episode transcript

[Music]

Charis Kubrin: So one activity I do with my students that I think illuminates this is I ask them, very first day, before they barely met me and know me – I ask them to close their eyes and think about an immigrant. You know, picture an immigrant in your mind.

Samantha Laine Perfas: This is Charis Kubrin, a professor at the University of California, Irvine. Charis studies the link between immigration and crime.

Charis: And often I'll put up a photo of my husband, who's an immigrant himself from Armenia, who's fairly light skinned. And I'll say, you know, Is this someone you had in mind? And of course, the answer always is no. Especially when we're talking about undocumented immigrants. And so what we do is we start breaking down some of the assumptions, and we start talking about how skin color, skin tone, all of these things play into stereotypes and assumptions that we have about immigration and crime in particular.

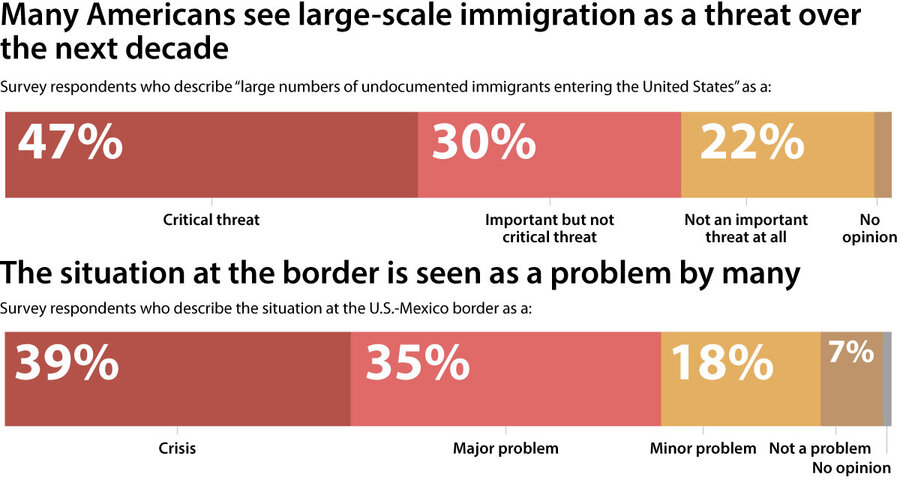

Sam: Charis’s students are not alone when it comes to these misperceptions. Many politicians still run on a “tough on crime” approach to immigration. And policies continue to be put in place to catch and deport unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. and reduce immigration into the country. The justification is often to keep Americans safe.

But the stereotype of the dangerous immigrant… that’s a perception gap.

[Theme music]

Sam: I’m Samantha Laine Perfas and this is "Perception Gaps: Locked Up," by The Christian Science Monitor.

[Theme music]

Sam: Welcome back to Season 2 of the series. In this season, we’re taking an in-depth look at mass incarceration. So if you haven’t yet, we encourage you to go back and listen to our two previous episodes – we look at the history of the U.S. prison system, and the role race plays in criminal justice. You can find all our material, including Season 1, at csmonitor.com/perceptiongaps.

In June 2019, a Gallup Poll found that 42% of Americans said immigration is making crime worse in the U.S.

But data show that’s not true. Research consistently finds that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than native-born Americans.

In 2019, for example, the Cato Institute reported that immigrants with and without documentation both have a much lower incarceration rate than Americans born in the U.S. A study published in 2018 in the journal Criminology found that unauthorized immigration does not increase violent crime. And yet another paper, by researchers at the University of California, Davis, showed that increasing deportations in areas with a lot of unauthorized immigrants didn’t reduce local crime rates.

It's true that many people come to the U.S. illegally. But if we're going to resolve the tough questions surrounding our immigration system, it's important that we don't equate "immigrant" – even "unauthorized immigrant" – with "criminal."

In this episode, we’ll look at why this perception matters, the policies that have resulted from it, and the impact on families, communities, and the criminal justice system.

[Music]

First, let’s go back to Charis Kubrin. She made it pretty clear to us that the research we mentioned about crime and immigration – those are just the latest findings. Criminologists have done variations of these studies for years.

Charis: You would be hard pressed to find even one criminologist in the field who would say immigration and crime go hand in hand. This is such an established finding. It's very rare that we have so much consensus around a finding. So it's very frustrating, because as much data as we have, the gap between perception and reality stays pretty – pretty firmly established.

Sam: Then why does that misperception exist?

Charis: I mean, I think it stems from everything from lack of understanding of what the data have to say, to racism, to bias, to misinformation, to politics.

Sam: But, according to Charis, the one factor that really stands out is fear.

Charis: It's very easy to play on people's fears by saying, “Look, we have a crime problem in the United States and it's largely due to immigrants.” Fear can be driven not so much by empirical data, but often stories that becomes kind of the rallying cry for those who believe that immigration and crime go together.

So fear is central to all of this.

[Music]

Sam: When allowed to dominate rhetoric and drive policy, fear can have immediate consequences. It feels like a long time ago now, but we saw this at the beginning of 2020.

[Audio clip from ABC News: “...the top Iranian general has been killed in an airstrike..”]

[Audio clip from CBS This Morning: “...is a dramatic escalation in the confrontation between the U.S. and Iran…”]

In early January, President Donald Trump ordered the killing of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani via drone strike. It was a response, U.S. officials said, to ‘an escalating series of attacks’ by Iran. After that, political tensions between the two countries surged.

Dozens of Iranians and Iranian Americans – many coming from vacation or work trips – were stopped by the Department of Homeland Security along the border with Canada. Some Iranian students were deported even though they had valid visas.

Hoda Katebi: These are students in the middle of Ph.D.’s. These are students in the middle of master's programs. And their lives are turned completely upside down.

Sam: This is Hoda Katebi, a writer and activist who helped organize support for those students.

Hoda: Iranians already were not getting visas very easily to come here. And even after being vetted, we’ve seen dozens and dozens of Iranian students on valid F1 visas arrive in an airport and then on arrival be detained for maybe 10, 15, 20 hours, sometimes yelled at, interrogated, cursed at, intimidated, and then deported.

Sam: For Hoda, the situation felt personal. As the daughter of Iranian immigrants, she was often regarded with prejudice and fear in her hometown.

Hoda: Growing up in Oklahoma as someone who is visibly Muslim – so I wear the hijab, and I started wearing it in sixth grade – that was a way in which I had normalized such a deep level of violence for myself. Like I thought it was normal to be called a terrorist. I thought it was normal to cross the street and someone to pretend to run you over. That was just my everyday growing up.

Sam: Can you talk a little bit about the concept of being “othered”? What does that mean and what does that feel like?

Hoda: I don't think I've ever been asked that question. I think that it's, it’s a very difficult experience to grow up in a place where no one looked like me, and everything that you believe in or everything that you look like is always bad and different. It affects every single aspect of our sense of beauty, our sense of confidence. And I think that that's something that is – it doesn't go away easily.

Sam: Why do you think that feeling of being othered is such a common experience for immigrants?

Hoda: Well, I mean, I think that this country is built on othering. And I think that that's really important to contextualize, is that this country has always made it incredibly difficult for immigrants and refugees to come to this country. What we’re seeing right now is something that also isn’t new.

[Music]

Sam: The Trump administration has been aggressive on immigration enforcement, and the president’s rhetoric is prone to linking immigrants and crime. But – and this is an important ‘but’ – President Trump is far from the first politician to draw a line between who belongs here and who doesn’t.

Muzaffar Chishti: You know, people forget that for the consummate nation of immigrants that we are, America has always been ambivalent about immigration.

I’m Muzaffar Chishti, I'm a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

Sam: Muzaffar has worked on immigration policy issues for decades. He says that Americans have been trying to keep certain people from coming here – basically since the country was founded.

Muzaffar: We didn’t like criminals. We didn’t like prostitutes. We didn’t like people who were going to become public charges in our country. We didn't like illiterates.

Sam: For example, in the 1800s.

Muzaffar: We had strong campaigns in the form of the creation of the Know Nothing Party, which was completely against the Irish and the Catholics in general, that these were just unsuitable members of U.S. society. And then we had, beginning in the 1880s, a campaign against Chinese. We had the Chinese Exclusion Act put in place in 1882.

Sam: Muzaffar says that no matter who the new arrivals were, the message was always some variation of: “They’re not like us. They’re tainting our values and culture. They don’t belong.”

Muzaffar: These are recurrent chapters of anti-immigrant hysteria, so that we began the 21st century essentially the same way as we began the 20th century, which is with mass migration. That level of mass migration was when Congress got extremely upset that wrong kinds of immigrants were coming – large numbers, and wrong kinds of immigrants. What they meant was Eastern and Southern Europeans – Italians, Greeks, Slavs, Russians, and Jews. Nordic supremacy was the hallmark of American immigration.

Sam: In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act.

[Audio clip from KCTS9, President Lyndon B. Johnson: “...that those who seek refuge here in America will find it.”]

The law was supposed to make U.S. immigration policy more racially equitable, in part by ending quotas that were biased toward immigrants from northern and western Europe. Over time, this law changed the demographic makeup of the entire country.

Muzaffar: ‘Til 1965, about 85 percent of our legal immigration was European or Canadian. Today, 85 percent of our immigration is Asian and Hispanic, fundamentally. So the frame changes, but race is always an important part of the immigration debate.

Sam: This history of racist attitudes toward people coming into the country helps explain why the stereotype of the dangerous immigrant is so persistent. But race is only part of the story.

In previous episodes, we talked about how the 1980s and ‘90s saw an unprecedented expansion of our prisons and jails as a result of “tough on crime” laws. Those ideas also seeped into the immigration debate.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, for example, increased border patrol and made it illegal to hire unauthorized immigrants. And as the Cold War raged, national security – and the security of American jobs for Americans – became the basis for calls to restrict immigration.

[Action News clip: “...Good evening. Politicians from several states tonight are sharply criticizing President Carter’s handling of the Cuban refugee problem. The governor of Texas, Bill Clemens, says the president has literally opened the floodgates…”]

The Clinton administration also cracked down on immigration in the ‘90s, as Mexico faced a recession that sent thousands of people north to find work.

[Audio clip from CNN, President Bill Clinton: “...in this country are rightly disturbed by the large numbers of illegal aliens entering our country. That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more. By hiring twice as many border guards. By deporting twice as many criminal aliens as ever before…”]

Then, after 9/11, the Bush administration created the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE. Billions of dollars went into militarizing the border.

[Audio clip from C-SPAN, President George W. Bush speech: “We got to strengthen security along our borders to stop people from entering illegally. In other words, we got to stop people from coming here in the first place.”]

And under President Obama, the U.S. deported more people from the country than at any other time period.

[Music]

These policies went a long way toward cementing, in the minds of the public, that crime and immigration go hand in hand – even though they don’t. The 2008 recession didn’t help, as millions of suddenly unemployed Americans looked for someone to blame.

Jonathan Metzl: This idea that – that somebody else is gaming the system is a very powerful, a very powerful script. ‘It's not our fault. It's these people's fault. You know, these immigrants who are pouring over the borders and taking all of your jobs.’

Sam: This is Jonathan Metzl, a professor of sociology and psychiatry at Vanderbilt University. In 2019, he published a book called “Dying of Whiteness,” about the consequences of white racial resentment.

Metzl: The book looks at the effect of a particular kind of politics in the United States, politics that stops people from joining together and forming alliances and forming common cause, particularly because of racial anxieties linked to whiteness. These racial anxieties – this idea that basically undeserving immigrants or minorities were going to come and take away your stuff or your privilege – pushed white voters into supporting positions that definitely targeted minority populations.

In social psychology, they call it a zero-sum formulation – that there are only so many resources, and these bad people are going to use them all up and there won't be enough for me.

Sam: In 2016, the political power of this idea became clear.

[Audio montage, President Donald Trump: “...they’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists…” “...are tonight, roaming free to threaten peaceful citizens…” “...we will build a great wall along the Southern border..”]

Muzaffar: This is the first time in our history – not just in our modern history, in our history – that any person has become the president of the United States on a strong anti-immigrant narrative.

Sam: That’s Muzaffar Chishti again, from the Migration Policy Institute. He says that while we’ve seen other candidates run on that message in the past, they almost never made it beyond their primaries.

Muzaffar: Here you had a person who not only won the primary of a major party, but then became the president on that playbook.

Sam: So what does that playbook look like for those most affected by it? When the government is guided by leaders who have emphasized the idea that refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants are dangerous, how does that affect immigrants and the communities around them?

[Music]

Laura Peña: My name is Laura Peña. I’m an immigration attorney and advocate. I serve as pro bono counsel for the American Bar Association, Commission on Immigration.

Sam: We reached out to Laura because she is living and working at the center of our immigration debate right now. She was born and raised in South Texas, along the border with Mexico. For years she was an attorney for ICE, presenting – among other things – the government’s case against immigrants seeking asylum in the U.S. Now Laura works on the other side of the courtroom, defending the migrants she used to prosecute.

My colleague Henry Gass, who covers Texas and the border for the Monitor, led the conversation with her.

Henry Gass: So I'd like to start with your experiences growing up on the border. I mean, you, you grew up in the Rio Grande Valley, I believe. Can you talk a bit about that? Tell us what that was like?

Laura: So if anybody is familiar with the Rio Grande Valley, it's the southernmost tip of Texas.

In terms of the border, the border really didn't exist the way it does today. There was a real back and forth flow of people, goods. We would celebrate our Christmas Eve at a well-known restaurant on top of a pharmacy in Matamoros called Garcia’s. My dentist was on the Mexican side of the border. So there was a real back and forth, ease of movement. And it just felt like one community.

Henry: Earlier in your career, you worked with ICE as a prosecutor. Can you tell us sort of when that was and why you wanted to do that?

Laura: I had a long love affair with law school. It took me about seven years to finish law school at night. When I finally finished, I decided that I wasn’t going to do policy work, so I moved out to California. And I realized I really do – I do love the law and I want to get any job that will immediately put me into a courtroom.

And when I saw the position with ICE, I consulted with mentors of mine, you know, they advised me that I would have an extreme amount of power and authority over the cases that I would see, that I would learn immigration law from the inside very quickly, and that more people with my mindset, with my background, with my experience growing up – my sensibilities, I guess – should be on that side of the table. And so I took that advice to heart.

Sam: This was during the Obama administration. At the time, ICE was facing criticism over how it was handling a surge of unaccompanied children coming to the border from Central America.

Henry: What was that like for you, working in the system at that time?

Laura: It was challenging to be inside the system, to see what the system's response to that border surge crisis was. I remember one hearing in which a six month old was called. It was a six month old baby. And the judge calls the case forward, doesn't realize that it’s a six month old that can't speak on the record. The judge was furious. How is she supposed to try a case for a six month old? And it turned out it was an administrative oversight. The six month old baby had crossed with her mother and the mother was also in proceedings. But somehow the files had been separated.

And I remember the judge's fury at me saying, you know, ‘We need to make sure that these cases are together. There's no way these children can be prosecuted separately.’ And I agreed with her at the time.

But in L.A. and in San Diego, I wasn't really seeing those cases on a day to day basis. I was mainly seeing the cases of the families who had been released and had moved elsewhere after being on the border. And they wanted to make sure that they followed the process.

Sam: Laura was never fully comfortable with her role at ICE. One of the last straws for her: a case that involved a woman seeking asylum from an African country where sexual violence was being used as a tool of war.

Laura: I tried that case, and I impeached her on the stand because she had a fraudulent, I think it was a voting I.D. card, something to that effect.

And as the judge denied her case, she broke out into a panic attack, wailing. And the medics had to come and take her out of the courtroom. But I knew, I knew that I had a hand in sending her back to be tortured. And I will live with that for the rest of my life.

Sam: Laura left ICE just before the 2016 election. After President Trump won, he started turning his campaign promises into policy. Family separations happened more frequently under the “zero tolerance” policy announced in 2018. The Trump administration said it was necessary to check the tide of unauthorized immigrants coming to the border.

Henry: What has it been like since then, sort of working as an immigration attorney on the border during this presidency?

Laura: What I see on the border is a pummeling of the rights of asylum seekers, the rights of even the border, the border residents, you know, the border wall being constructed with such intent to separate and divide what is really a binational community. So at a very personal level, it’s been extremely challenging to see the borderlands portrayed as a dangerous place where this invasion is occurring.

From a legal perspective, it's been doubly as challenging. You can't keep up with the policies that this administration continues to announce, continues to implement. So it’s been – it’s been a struggle.

Sam: Before we hear more from Laura and Henry, I want to turn back briefly to Muzaffar Chishti at the Migration Policy Institute. In our conversation, he brought up some important misperceptions about illegal immigration, which is often at the core of our ideas about the border and who comes through there.

Muzaffar: One of the myths about immigration is that as if all our immigration is illegal immigration. That is just not true. For the one million people who come to the US as permanent residents every year, they all come through sponsorships either by a U.S. family member or by a U.S. employer.

Sam: According to the Migration Policy Institute, around 9 million people came to the U.S. as visitors or temporary residents in 2018.

Muzaffar: They're coming as students, they're coming as temporary workers to work for employers. They're coming as exchange scholars. They're coming as seasonal workers. Or they’re just coming for, you know, for a visit, for pleasure.

Sam: And that’s not including the tens of thousands of people, mostly families from Central America, who come to the U.S. legally seeking asylum. And yet:

Muzaffar: One-fourth of our foreign-born population today is unauthorized. That has never been true in our history. And that creates its own feeling of disquiet.

Sam: So how does that math work? Who are the majority of these immigrants, and why are they coming without the right papers?

Muzaffar: The fact is that while we have become reliant on immigrant workers – and this is true much more in the low-wage sector – our legal channels for low-skilled workers and low-wage workers have almost disappeared. This is sort of one of the biggest misconceptions about immigration, as though people choose to come illegally.

Sam: To put this in context, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that , pre-COVID-19, openings for low-skill jobs – like health care aides, janitors, and farm workers – soared over the past decade. But of the 1 million green cards per year that we issue to new permanent residents, only about 1 percent are available for those workers. Other visa categories for low-wage and seasonal workers, like H-2A visas, also either fall short or are so tangled with red tape that they’re nearly dysfunctional.

Muzaffar: So the workers are filling the jobs using illegal channels because legal channels just don't exist for them. Which is what has then created the pool of unauthorized workers up to one-fourth of our foreign-born population. And that is the core of our illegal immigration problem.

And when people talk about comprehensive immigration reform, that's what they're talking about, is that we need to redesign our immigration selection system to accommodate for the realities of our labor market needs.

[Music]

Sam: When immigrants come to America, especially poor immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, they often encounter a legal system that both reflects and is deeply tied to our system of criminal justice. Here’s my colleague Henry Gass again, with the lawyer Laura Peña.

Henry: Is the immigration system different from just the, the justice system that U.S. citizens interact with around the country?

Laura: In many ways, the immigration system is a lot worse than the criminal justice system, because the constitutional protections that are afforded to defendants are not available for immigrants. So there is no right to an attorney in the immigration system, and that results in a very, very low percentage of individuals who have access to attorneys.

There are similarities, though. You have mass incarceration of Black and brown men at alarming levels.

Sam: On any given year, around 360,000 immigrants are locked up in American detention facilities. Which is a big number, and numbers like that are important in these conversations. But – and we brought this up in our previous episode – it’s just as important to remember that behind every statistic is a real person.

Henry: You know, I think there's a question of humanity here. How do you think we keep humanity sort of at the center of immigration enforcement?

Laura: You know, you have to start with unwinding or unraveling some of the perceptions that Americans have of immigrants. Bringing humanity back into the system requires Americans to relearn what it means to be an immigrant in American society, and to not equate that with being a criminal. And as soon as we recognize asylum seekers, refugees, migrants, undocumented immigrants, whether they be coming to our borders now, whether they've been living in the shadows for the past, you know, decades – they are just like us. And for the most part, they also believe in the fundamental values that we do as Americans.

And only then I think, can you start bringing humanity as a center of immigration law and policy.

Sam: Thanks for listening, and we hope you’ll join us for future episodes. Our next episode will take you on the ground – to Evanston, Wyoming, a town that wrestled with the decision of whether or not to build an immigration detention center. If you’d like to stay in the loop, sign up for our newsletter at csmonitor.com/perceptiongaps. We’ll include show notes, videos, additional articles, and behind the scenes takes from the series – such as a story about a couple who got married on a cross-border bridge, where Henry first met Laura Pena. Again, you can sign up for it at csmonitor.com/perceptiongaps.

This episode was produced and hosted by me, Samantha Laine Perfas. It was co-reported with Henry Gass and co-produced with Jessica Mendoza, with additional edits by Clay Collins, Noelle Swan, Yvonne Zipp, Dave Scott, Em Okrepkie, Jules Struck, Lindsey McGinnis, and Kelsey Evans. Sound design by Morgan Anderson and Noel Flatt, with additional audio elements from KCTS9, Action News, CNN, Business Insider, and C-SPAN.

This podcast was produced by The Christian Science Monitor, copyright 2020.

[End]