Why US parks put land purchases on hold

Loading...

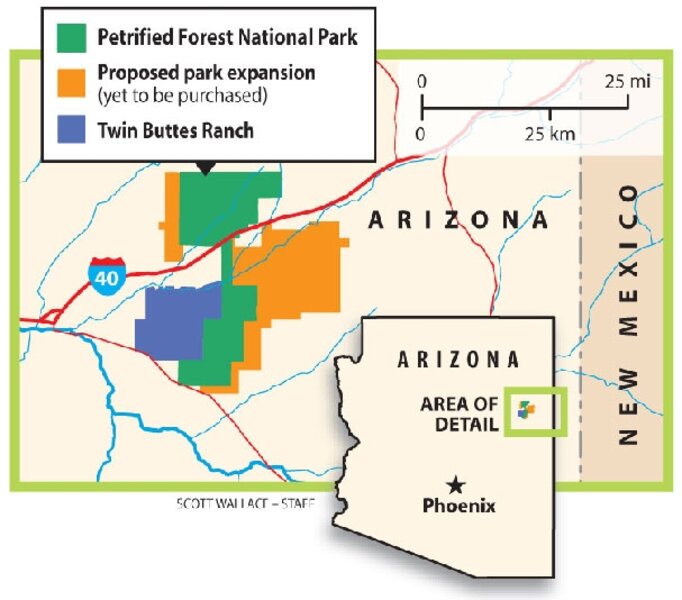

| Twin Buttes Ranch, Ariz.

Standing beside a barbed-wire fence that once kept cattle from roaming off his sprawling 28,000-acre ranch, Mike Fitzgerald gazes into the distance and sweeps his hand across the pale horizon.

“I wanted this ranch to be part of that national park some day,” he says, pointing to a distant rocky plateau shimmering in the heat. “I’ve tried for so long to sell it to the government. But I’m not sure now that will ever happen. I can’t wait forever.”

Hammered by drought in this rugged slice of northern Arizona, Mr. Fitzgerald sold his cattle a few years ago. Now he’s eager to sell his ranch – rich with ancient petroglyphs, petrified wood, and dinosaur fossils – to the National Park Service so it can become part of the Petrified Forest National Park next door.

It might seem an obvious and natural step. Congress thought so in 2004, when it formally expanded Petrified Forest’s boundaries to add Fitzgerald’s Twin Buttes ranch and other nearby parcels. But a lack of funds to buy the Fitzgerald land due to a shift in Bush administration and congressional priorities has delayed and perhaps killed the deal.

At this point, Fitzgerald says he’s exhausted. So instead of his land becoming a new jewel in an expanded national park, he may now sell to developers who would carve his ranch into 40-acre “ranchettes.” Or, they may mine it for buried petrified wood, valuable when polished and sold as bookends and other ornaments.

It’s a plight similar to scores of cases nationwide in which the character of national parks is threatened by impending development on their borders – even inside the park itself.

Threats to wildlife, open space, and cultural treasures – not to mention the prospect of a hotel popping up to despoil a natural vista – exist on up to 1.8 million acres of privately held parcels that the National Park Service would like to buy but cannot, according to a recent study by the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), a nonprofit advocacy group.

That huge backlog, which includes private land awaiting purchase inside parks (called “inholdings”) as well as neighboring parcels, is partly due to the glacial rate at which they’re being acquired. That reflects a lack of funds for land purchases – and a shift in priorities, observers say. Despite their potential historical value and proximity to parks, these inholdings and adjacent land are often unregulated and, many fear, vulnerable to development.

Park Service land-acquisition budgets were cut from $147 million in 1999 to just $44 million this year, a 70 percent drop. Most parks have had little funding for land acquisition for years. Yet there’s a limit to how long even public-spirited land-owners like Fitzgerald are willing to wait.

“Time is a real factor here,” says Greg Caffey, chief ranger at Petrified Forest National Park, gesturing over the park fence to a large excavator that has been digging up petrified wood on private land next to the park. “If we go another 10 or 15 years,” he says, “a lot of the scientific value of the land around us – including Mike Fitzgerald’s land – will be lost.”

The years of delay have now left important parks at acute risk, NPCA officials say. Inside Gettysburg (Pa.) National Military park, for instance, 1-in-5 acres is privately owned and could be commercialized.

In Zion National Park in Utah, just 10 strategically placed acres that could be purchased are instead drifting steadily toward development, NPCA officials say.

Even at Valley Forge National Historical Park in Pennsylvania, 78 privately held acres inside park boundaries that could have been purchased may now become a hotel, conference center, and museum – all within rifle shot of Gen. George Washington’s former winter headquarters.

“You’re leaving America’s heritage at risk,” says Ron Tipton, senior vice president for programs at NPCA. “Private owners have a legal right to get value for their property. If the Park Service can’t do that in a timely way ... we’re going to have situations like Valley Forge and Petrified Forest. When you only give the Park Service $30 [million] to $40 million, you can’t do it.”

The trail leads to Washington, D.C.

Buying up vulnerable land to eliminate potential development conflict with natural park surroundings has been a goal of Congress since the Land Water and Conservation Fund (LWCF) was set up in 1965 to purchase land for federal land agencies. It funds land purchases across the US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the National Park Service.

But under the Bush administration, budget requests for land acquisition funds for national parks fell from $172 million in 2000 to $21.8 million for this next fiscal year.

A Republican-led Congress had been cutting Park Service land acquisition budgets even faster than the administration – until Democrats took control in 2006 and restored some funding. This year, Congress appropriated $44 million, double the administration request. Land budgets can also be misleading, since just $13 million of the $22 million land-acquisition budget request this year is actually to purchase parkland. More than $8 million is for administrative services related to land acquisition.

“This administration has had a different focus for the parks,” says Jeffrey Olson, a spokesman for the National Park Service. “It’s been much more on operations and maintenance – maintaining what we have. It’s not been on adding new land to parks.”

Such shifts in administration priorities have been a big factor.

Prior to 1998, the lion’s share of the LWCF funding actually went to purchase land. But in recent years that has flipped around: Now most LWCF funds are spent on federal land programs that don’t actually purchase land, a 2006 Congressional Research Service (CRS) study found.

Just 7 percent of the LWCF’s $969 million funding went to such “other programs” in 1998. A dramatic shift began in 2001 with “other programs” leaping to 46 percent of the fund. By 2006, overall LWCF appropriations from Congress had shrunk to just $346 million. But within that total, the “other programs” share gobbled up almost two-thirds, the CRS reported.

Such “other” programs include, for instance, a new administration push for cooperative programs that pay private land owners to maintain natural resources on their land to support rare or endangered species living there.

Noble as they may be, such changed priorities in spending – along with budget cuts – have left little in the way of funds to buy parkland.

“There just isn’t any will in the current administration to preserve these parks and enhance them,” says Roxanne Quimby, a philanthropist who has purchased many acres in Maine on behalf of Acadia National Park.

“The administration’s position is strong that we have to take care of the land we have now,” the Park Service’s Mr. Olson says. “Budgets are tight and a war is going on.”

Whatever the reason, as the Park Service nears its 2016 centennial, it is left with a nearly 2-million-acre backlog of “priority land-acquisition needs” valued at $1.9 billion across 154 of 359 park units, NPCA says.

Land whittled away

Next door to Petrified National Forest at Fitzgerald’s ranch, fossils and petroglyphs are still intact, so far. But practically no research has yet been conducted on them – and scientists are eager to get going.

“The Twin Buttes ranch is a Rosetta stone for paleontology,” says David Gillette, curator of paleontology at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. “Not to acquire this land for the park would be a huge missed opportunity for the American public. It’s a scientific resource we can’t match anywhere else.”

There’s hope that some private inholdings will end up as parkland. In Maine, Friends of Acadia and the Maine Coast Heritage Trust have joined to purchase about 140 parcels worth about $40 million to fill gaps in Acadia National Park and prevent development in those areas.

Similarly, a charitable group played a key role in purchasing land in the middle of Picket’s Charge Field, is helping restore the land for Gettysburg National Military Park.

For his part, Fitzgerald has been aiming for a long shot: find a buyer willing to keep the ranch land undeveloped until the Park Service is able to buy it. He recently had to sell a small corner of his property to someone who is now using excavators to mine it for petrified wood, something that upsets him.

“I don’t want my land to get chewed up by mining or development,” he says. “But it’s getting to the point where I’m not sure what else I can do.”