- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

- Many Americans don’t trust elections. What can be done?

- With US leaving, Taliban tales of ‘victory’ and jihad lure youth

- ‘Time to do something’: Colombia protests now a family affair

- One of NASA’s ‘hidden figures’ writes her own story

- With giant trolls, one artist preserves imagination – and the environment

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How ‘car guy’ Biden captured Lightning

President Joe Biden is a car guy. You can hear it in his voice when he talks about (and then drives) his beloved 1967 Corvette Stingray, as he did on “Jay Leno’s Garage” in 2016. And he said as much Tuesday, when he visited the Ford Rouge Electric Vehicle Center in Dearborn, Michigan.

The president’s visit was meant to highlight a cornerstone of his economic agenda: investing in innovation and infrastructure while creating jobs and combating climate change. It was also a pretty good plug for Ford Motor Co., which just unveiled the F-150 Lightning – the electric version of its iconic pickup truck.

But a second agenda seemed clear, when President Biden made a request: “I want to drive this truck.” Soon, he was on the test track, wearing Ray-Bans, behind the wheel of a prototype Lightning. Ford CEO Jim Farley told him to “mash the throttle,” and he did.

“This sucker’s quick,” Mr. Biden said moments later.

Presidents almost never get to drive, for security reasons. So Tuesday was a rare opportunity. It was also a chance for Mr. Biden to be, well, a little macho and show some vigor. Images of President Ronald Reagan riding horseback and clearing brush on his ranch spring to mind.

Mr. Biden doesn’t have a big ranch where he can go drive around – as President Lyndon Johnson did in Texas – but for this “car guy” president, flying to Motor City and capturing Lightning may have been the next best thing.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Democracy under strain

Many Americans don’t trust elections. What can be done?

Leading up to the 2020 vote, Americans had mixed feelings about election integrity, with about 6 in 10 saying they did not trust the outcome to be fair. Rebuilding trust now looks like a high civic priority. Next in our series, “Democracy Under Strain.”

Can elections be armored against disgruntled efforts to subvert them? Complete trust in election outcomes is likely an impossible goal in today’s polarized political environment.

In general, there are really only two major factors that affect voter trust in an election, says Charles Stewart III, a professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The first is whether their candidate won or not. The second is whether they personally had to wait in a long line to cast their ballot.

But he and other experts say there are steps that can build trust that elections are free and fair. One might be regular election audits following established professional procedures, and which are largely the same in all 50 states.

Other experts are calling for a cross-discipline, cross-partisan effort to stop political disinformation. Legislation may have a role to play: for example, revising an 1845 federal law that could be exploited to use allegations of voting irregularities as a pretext for state legislators to override the vote.

In the end, it may be more than laws that hold together confidence in elections and democracy itself.

“It’s the expectations, the norms, the willingness to concede,” says Professor Stewart.

Many Americans don’t trust elections. What can be done?

America’s democratic process has been severely tested in the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election. Former President Donald Trump’s personal push to overturn results in key states revealed vulnerabilities in the nation’s electoral system – including how many important aspects of voting are defended not by laws, but by norms of official behavior.

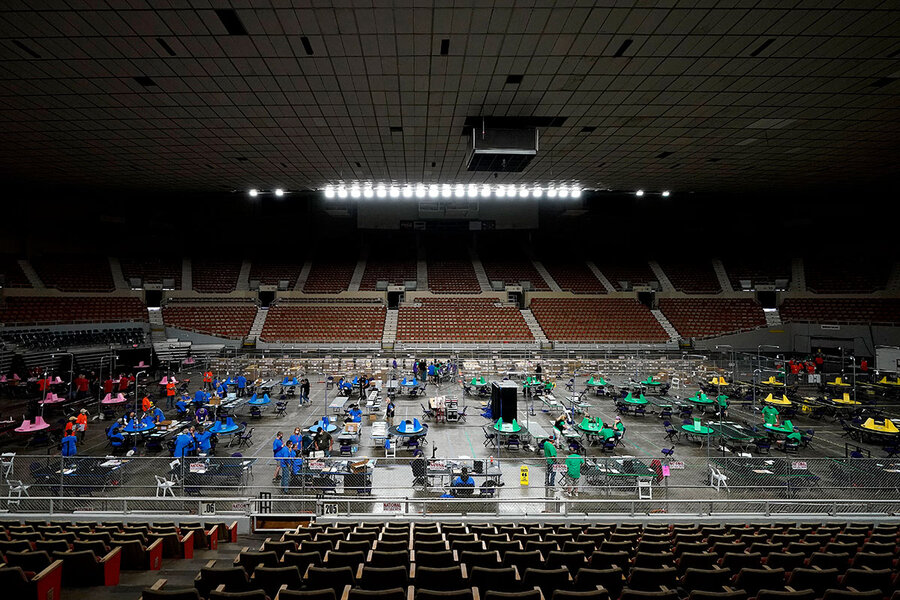

Nor has the testing ended, despite the Trump campaign’s dozens of losses in election-related lawsuits, the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and Congress’ ultimate certification of President Joe Biden’s Electoral College win. Despite no evidence that Mr. Trump’s loss in Arizona was fraudulent, 16 Republicans in the state Senate voted to subpoena ballots from Maricopa County, for an examination that has been widely criticized as a partisan ploy.

Trump supporters are now seeking Arizona-style “audits” in Georgia and other swing states.

Can elections be armored against disgruntled efforts to subvert them? Perhaps more important, can changes to the electoral system regain trust that has been lost on both sides?

Complete trust in election outcomes is likely an impossible goal in today’s polarized political environment. But it is possible to have trustworthy elections, ones that impartial observers can agree are free and fair, experts say.

Election audits could be akin to financial audits – activities that occur regularly, follow established professional procedures, and are largely the same in all 50 states, says Charles Stewart III, a professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“If we weren’t in the middle of partisan wrangling over the whole 2020 election, with crazy things happening in Arizona, we could have a reasonable discussion about making things better,” Professor Stewart says.

High levels of distrust

Americans have mixed feelings about elections, according to polls. Overall, they are not confident in their honesty. Heading into the 2020 vote, 59% of Americans said they did not trust the outcome to be fair, according to a Gallup survey.

But trust in specific elections can be higher. Sixty-five percent of Americans are confident in the outcome of the 2020 vote, according to a Morning Consult survey. There is a wide disparity in attitudes between members of the two big U.S. political parties, though: Ninety-two percent of Democrats said the election was free and fair, while only 32% of Republicans agreed.

In general, there are really only two major factors that affect voter trust in an election, says Professor Stewart. The first is whether their candidate won or not. The second is whether they personally had to wait in a long line to cast their ballot.

According to many of the Republican state legislators currently pushing for restrictions and clarification in voting laws around the nation, one of their primary motives is to make GOP voters feel more secure about election results. The irony is that those bills may be unlikely to affect confidence at all.

“There is no evidence passing new laws affects voters’ perceptions of election integrity,” Michael McDonald, a professor at the University of Florida who specializes in American elections, tweeted last month.

A roundtable on restoring trust in the American electoral process hosted by Election Law Journal last month produced a variety of medium- to long-term solutions for the problem.

The United States might take elections out of the hands of partisan entities and use nonpartisan experts to run them, suggested Guy-Uriel Charles, a professor at the Duke University School of Law. He used the analogy of a NASA for elections.

Congress might pass a law requiring the winners of congressional elections to get a majority of the vote in their districts, not just a plurality, said Ned Foley, a professor of election law at the Ohio State University. This could strengthen moderates in both parties and make it more difficult for extremists to squeak into office, Professor Foley said.

The country could also begin the long-term process of strengthening the kind of intermediaries that help with truth-telling and fact-checking in politics, such as the press, the judiciary, and opposition parties, said Rick Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine.

There really needs to be a cross-discipline, cross-partisan effort to stop political disinformation, said Professor Hasen. Many of the efforts to pass new voting regulation laws stem from the success that Mr. Trump has had hammering home the false “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was stolen.

“If there’s going to be 30% of the population that doesn’t agree with truth, we’re not going to get out of this situation,” Professor Hasen told the roundtable.

Revisit an 1845 law?

Trust in elections might also be helped by enacting some basic safeguards against flaws in the electoral system exposed in post-election struggles.

One of the biggest such holes was the prospect that legislatures in key swing states would override the popular vote in their states and appoint Electoral College electors themselves, says Richard Pildes, a professor at the New York University School of Law and co-author of “The Law of Democracy: Legal Structure of the Political Process.”

Then-President Trump called on state legislators to do just that. This sheds light on a previously little-known provision in federal election law known as the “failed election” provision, says Professor Pildes.

Dating back to 1845, this provision says that if any state “has failed to make a choice on the day prescribed by law,” state legislatures may step in and do it instead. But the definition of “failed” is vague, and it is possible that partisans could use allegations of voting irregularities to claim failure that necessitates lawmakers to act.

Congress should clarify that this applies only if natural disasters or similar events make it impossible to conduct a proper election, he says. Otherwise, the ongoing Arizona audit could be a template for trouble in 2024, with swing state legislatures drawing up lists of alleged violations, and then leveraging those into investigations and subsequent legislative intervention.

“It remains among the most potentially destabilizing provisions in federal election law,” says Professor Pildes, calling it a “loaded weapon” waiting to be used.

Not just laws, but maturity and norms

Sweeping Democratic-backed election reform bills now before Congress deal largely with voting access and other aspects of the U.S. electoral system, not protection against subversion or explicit rebuilding of trust. Meanwhile, state voting bills such as recently passed legislation in Georgia and Florida in fact weaken local election administration, and thus might be called “democratic backsliding,” says Jennifer McCoy, a political science professor at Georgia State University.

In Georgia, for instance, the new law would allow the GOP-controlled State Election Board to replace election officials in heavily Democratic local counties based on performance or violation of election board rules. The law contains specifics limiting the circumstances in which it can be used, but Professor McCoy says it echoes changes made in other countries such as Venezuela, where elected autocrats gradually gained more and more control over the country’s election machinery.

“This reminds me of that,” says Professor McCoy.

But in the end, it may be more than laws that hold together confidence in elections and democracy itself.

“It’s the expectations, the norms, the willingness to concede,” says Professor Stewart of MIT.

These problems did not start with the 2020 election, and they won’t end by 2024, either. Election administration can’t necessarily constrain bad-faith actors or even just highly disappointed losers, he says.

“We have to be mature enough to recognize there are no perfect elections. ... There becomes a margin at which even the best-executed rules and procedures will leave some room for doubt. That’s where the norms of the political process have to kick in,” says Professor Stewart.

With US leaving, Taliban tales of ‘victory’ and jihad lure youth

Despite the insurgent Taliban’s atrocities and their grim past rule, why do they still exert a real gravitational pull? A window into Afghanistan’s Wardak province, and the story of one jihadi.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Promising to overthrow the “infidel” government of President Ashraf Ghani and reestablish their Islamic Emirate, the Taliban have been launching a fresh drive to recruit young men. As the United States speeds up its withdrawal from Afghanistan, that drive is leveraging the Taliban narrative of “victory” over a superpower in war, coupled with praise for the glories of jihad and martyrdom.

And despite grim memories of the Taliban’s severe rule and a history of atrocities during their yearslong fight against American forces and the Kabul government, the insurgents are succeeding at boosting their numbers.

Noori, a government employee in Kabul, traveled throughout Wardak province last week and says he was surprised by what he found. “The Taliban warlords campaigned hard for recruits during Ramadan,” he says. “Unlike in the past ... I saw that half of the village youth and teenagers had joined the ranks of the Taliban.

“I asked some of those youth who freshly joined the Taliban, ‘Why are you doing this?’” recalls Noori. “They said with great pride that the insurgency of the Taliban was able to defeat the infidels, and we are honored to be martyred in this way, to establish an Islamic system in Afghanistan.”

With US leaving, Taliban tales of ‘victory’ and jihad lure youth

In life, Saheel was a young, improbable Taliban commander who launched multiple attacks against Afghan National Army bases.

But in death, Saheel – who detonated a car bomb May 8 that killed 12 Afghan troops in the Saydabad district of Wardak province, only to be killed himself by a surviving Afghan soldier – has become another tool in a fresh Taliban drive to recruit young men to their jihadi cause.

He is just one of a new crop of young men riding Taliban promises of overthrowing the “infidel” Afghan government of President Ashraf Ghani and reestablishing their Islamic Emirate.

As the United States speeds up its withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, that Taliban drive is leveraging their narrative of “victory” over a superpower in war, coupled with praise for the glories of jihad and martyrdom at local mosques.

“It is not possible to forget this handsome man … may God accept His martyrs who follow the path of God,” reads one memorial to Saheel posted on Facebook that aims to encourage fellow jihadis. It shows the fresh-faced, 19-year-old Taliban captain, with long hair and a thin mustache, sitting at ease in a field of grass, holding a set of prayer beads.

The examples of Saheel and his native Wardak province west of Kabul, where the Taliban largely hold sway, provide a window into how the gravitational pull of the Afghan insurgents has grown, especially among would-be recruits. And how that pull prevails, despite grim memories of the Taliban’s severe rule in the 1990s and their subsequent atrocities against civilians while fighting American forces and the U.S.-backed Kabul government.

This rare window shows how the Taliban are succeeding at boosting their numbers, able to convince even those like Saheel, who family members say despised the Taliban – until he joined them 2 ½ years ago.

A Ramadan campaign

Noori, who is from Wardak and works in a government office in Kabul, spent the three-day Eid cease-fire last week traveling throughout the province and says he was surprised by what he found. The cease-fire was called for by the Taliban and reciprocated by Afghan forces.

“The Taliban warlords campaigned hard for recruits during Ramadan,” says Noori, who asked that only one name be used for his safety. “Unlike in the past, during this Ramadan, when I went to the village, I saw that half of the village youth and teenagers had joined the ranks of the Taliban.

“I asked some of those youth who freshly joined the Taliban, ‘Why are you doing this?’” recalls Noori. “They said with great pride that the insurgency of the Taliban was able to defeat the infidels, and we are honored to be martyred in this way, to establish an Islamic system in Afghanistan.”

Noori says he took part in prayer sessions where speeches of religious leaders and local Taliban figures were “about the virtues of jihad and martyrdom … and they were told it was [the Taliban] that defeated the great power of the world, the United States.”

Local men were aroused further by claims that President Ghani’s government “targets and kills mullahs and religious scholars” and had “no clerics left,” which was enough to convince one 14-year-old boy to want to join the fight, says Noori. The Taliban promised no payment – just the “highest degree of martyrdom … as heirs of the Prophets on the Day of Judgment.” He says he saw some young Afghans buy weapons with their own money.

“Taliban on the battlefield do not believe in peace,” adds Noori. “They think they have defeated the United States, and their efforts are toward war.”

The victory narrative

The Taliban vowed a “reaction” when the U.S. ignored an initial May 1 pullout deadline, signed by U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad and the Taliban in February 2020. President Joe Biden stated that several thousand remaining American troops will instead depart by Sept. 11 – the 20th anniversary of the attacks on the U.S. that first brought American forces to Afghanistan.

Analysts say then-President Donald Trump’s race for the exit meant the Taliban gave up little in the February 2020 deal, in exchange for a concrete U.S. pullout timetable. Direct negotiations with Washington also provided unprecedented legitimacy to the group.

“By bending over backwards to the Taliban, [Ambassador Khalilzad] gave them an opportunity to develop this victory narrative, and they are great on getting leverage from it,” says Michael Semple, an Afghanistan expert and former European Union adviser in Kabul, now at Queen’s University Belfast.

Many Afghans suggest “it was the Americans that revived the Taliban,” not the Taliban themselves, he says. And that has given the Taliban more ammunition to pursue defections, for example, by pressuring tribal elders to approach local Afghan security force bases, promise guarantees of safety, then chide the young men to abandon their posts.

“That’s actually been a very simple, quite effective tactic for the Taliban,” says Mr. Semple, who just returned from a three-week research trip to Afghanistan. “A lot of the ground they are making is without a shot fired.”

Taliban propaganda also highlights these defections, to encourage more. Nearly every day its Voice of Jihad website lists details and photographs of “enemy personnel” who “join the Mujahideen” – sometimes in large batches. These servants of the “puppet” administration are noted to have “realized their mistakes.”

Giving the impression of a well-oiled war machine, the Taliban also produce slick videos of their fighting prowess. And a recent photo essay, titled “Hundreds graduate from military camps,” appears to show legions of fully equipped commandos.

Maintaining strength

It’s an impressive show for jihadis the U.S. military says suffer thousands killed in battle every year. Yet estimates of Taliban strength, which range from 50,000 to 100,000 fighters, have not dipped, says Andrew Watkins, senior Afghanistan analyst for the International Crisis Group.

“What does that say about Taliban recruiting?” asks Mr. Watkins. “If nothing else, they’re replenishing their losses in the deadliest conflict on the planet. That’s staggering, especially when you think about the struggles the Afghan security forces have in recruiting.”

The time-consuming effort to list details “of all the people, who may have abandoned this or that position,” may appear to be “boring PR” to outsiders, but has recruitment benefits, says Mr. Watkins.

“It’s not necessarily a sign of Taliban strength,” he says. “It could be of insecurity and a need to be perceived as attracting people to the winning side.”

While that is how Saheel’s death is being used by the Taliban today, it is not the reason he joined. In fact, his family says, his story begins with a lifelong desire to be a soldier in the Afghan National Army. But the day the top student was filling out the forms, his father forbade him from joining – insisting instead he become a doctor.

Angry and frustrated, Saheel left home that day, family members say. He fell under the influence of Taliban cousins. Another cousin had previously been killed in fighting.

“My son was always against the Taliban. He never wanted to be with this group,” says Saheel’s mother, who, like all family members interviewed, asked not to be named. The cousins took Saheel to mosques “where the Taliban talked about jihad and extremism. … They brainwashed Saheel and changed his opinion,” she says.

“I want to be martyred”

In contrast, Saheel’s older brother, a university student, says he prays “every day for peace,” and mourns the death toll.

“I have lost my brother, but I do not want to lose other young people anymore,” says the brother. Lack of peace means “all youths will be sacrificed on both sides,” and the winner will “rule over cemeteries.”

Recruiting for that win is easier today for the Taliban, with rampant youth unemployment and hopelessness – and the Taliban tale of battlefield momentum.

“The Taliban are exploiting the feelings of the new generation and teenagers who are at a vulnerable age,” says Saheel’s uncle. Saheel called him last month, asking for money to buy a bicycle. The uncle brought a bicycle to their meeting, and tried to convince Saheel to leave the Taliban.

“Saheel said, ‘No, I want to continue the jihad until America leaves our homeland, and I want to be martyred in the way of God – this is my only wish,’” the uncle recalls.

That is no surprise to Saheel’s mother, who twice tried to convince her son to leave the Taliban – most recently during Ramadan, when he called. She told him peace might be coming.

“But Saheel said to me, ‘I pray to God that I will be martyred before peace comes,’” the mother recalls. “That was the last time I talked to Saheel.”

A correspondent in Kabul contributed reporting.

‘Time to do something’: Colombia protests now a family affair

A year of pandemic hardships has affected all ages, and in Colombia, citizens have come together in protest. Their frustrations could signal what’s to come across the region, as countries juggle a desperate need for austerity with citizens’ exhaustion.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Steven Grattan Correspondent

Carlos Camargo always supported protests for equality and better government services in Colombia, but it wasn’t until this month that he took action. Alongside his wife, adult children, and son-in-law, he marched through the streets of the mountainous capital demanding change.

“We are all fed up with the bad management of the current government,” says Mr. Camargo’s daughter, Jessika. After a tax reform proposal that many worried would hit middle class and poor people hardest – after a year of pandemic-related struggles – the family decided together “it was time to do something instead of just complaining,” Ms. Camargo says.

The unrest may be a harbinger for what’s to come across Latin America. The region has been hit particularly hard by the pandemic, with high death tolls, pummeled economies, and slow-to-arrive vaccines.

“There’s a lot of older folks who really want to leave a better country for their children, and a lot of children … telling their grandparents ‘Look, you have to march because of the environment or because of pension reform or health care reform,’” says Sergio Guzmán, director of Colombia Risk Analysis. “These protests have brought together a very diverse cast of characters that makes a formidable opposition to the government.”

‘Time to do something’: Colombia protests now a family affair

For the first time in his life, 63-year-old Carlos Camargo took to the streets in protest this month.

On May 1, alongside his wife, two adult children, and son-in-law, the recently retired plastics factory worker decided it was his time to raise his voice for the government to hear.

“I’ve always supported these types of protests – I think they are necessary – but I’ve never gone out myself,” says Mr. Camargo. He has noted an uptick in poverty in the mountainous capital, Bogotá, and is concerned only wealthy people will emerge from the pandemic’s struggles above water. The protesters’ loud chants and the fluttering of Colombian flags he witnessed during the demonstration have stayed with him.

“We are all fed up with the bad management of the current government,” says Mr. Camargo’s daughter, Jessika, who works for a nonprofit organization. This is the first time she’s protested with family members. Together, they decided “it was time to do something instead of just complaining.”

Unrest has spread across Colombia since a tax increase proposed by the right-wing government of President Iván Duque last month, which he argued was urgently needed to shore up the pandemic-hit economy. Violence quickly escalated in big cities, with almost 50 people killed, many at the hands of police.

Although the proposal sparked the protests, public frustration goes far beyond it. The poverty rate in Colombia went up nearly 7% over the past year, to 42.5%, according to Colombia’s national statistics agency. Today, protesters’ demands have grown to include everything from universal basic income to halting health care privatization to the dissolution of Colombia’s riot police.

The widespread discord after more than a year of pandemic-related lockdowns and losses may be a harbinger for what’s to come regionally. Governments across Latin America are faced with jump-starting pummeled economies, while citizens increasingly lose patience awaiting slow-to-arrive vaccines and a return to some kind of normalcy. Even pre-pandemic, Latin America had one of the highest levels of inequality in the world. The presence of entire families on the streets of Colombian cities put front and center how the past year has exacerbated preexisting challenges that are acutely hitting people regardless of age, race, or occupation.

“We know that the pandemic has affected people terribly,” says Ms. Camargo. Protesting with her parents and brother “was important for me because it shows that the protests aren’t only for young people and students.”

Underlying unemployment, poverty rates, and inequality have contributed to Colombia’s unrest, says Sergio Guzmán, director of Bogotá-based Colombia Risk Analysis.

“The pandemic worsened all of those problems at the same time,” he says. “The tax reform added insult to injury, because it didn’t address this issue of inequality and unequal tax distribution.”

“Better opportunities”

From a humble background, Mr. Camargo began working when he was 15. One of his main reasons for joining these protests was indeed the tax reform, which he believed would shield the rich while battering the working classes.

The increase in poverty over the past year has been impossible to ignore, Mr. Camargo says. Extreme poverty more than tripled in Bogotá between 2019 and 2020, when the pandemic upended the economy.

“There are more people on the streets, begging at the traffic lights, more are competing to clean the car windows for money,” he says. Personally, he’s felt a crunch since retirement last year, but his children’s future is on his mind, too. “I want my children and grandchildren to have better opportunities,” he says.

President Duque’s tax proposal would have removed some tax exemptions and lowered the threshold for who must pay income tax. Days after the demonstrations began, he withdrew it, directing the legislature to quickly draw up a new plan to “avoid financial uncertainty.” He has attempted to hold talks with major unions and other groups in charge of organizing national strikes and protests, but they have yet to sow results. Many citizens in cities like Cali are suffering food and fuel shortages as more extremist protesters enforce blockades and halt supplies from entering the cities. Last week, weapon-wielding civilians tried to disperse demonstrators from roadblocks, further raising tensions and propelling a last-minute visit from Mr. Duque to calm the situation.

Mr. Guzmán, the political analyst, says Colombians felt the tax reform was untimely and would make their lives more expensive. Many were further frustrated in the days following the tax reform announcement when the finance minister woefully underestimated the price of a dozen eggs in a television interview.

“You can argue about the [tax reform] numbers all day long, but you can’t argue about the simple fact that the government and many of the members of the ruling party showed a huge disconnect with people,” Mr. Guzmán says. “The tax reform became a trigger for this wave of anger that had been repressed and pent-up for a while.”

Police crackdown

Security forces’ clampdown has further unified opposition, drawing people of all generations to the streets.

“I absorbed the energy of the young people there,” says María del Pilar Barbosa, a Bogotá business owner in her 50s who went out to protest with her daughter, Daniela, for the first time. They attended a special march for the mothers of children who have died during protests. “It hits you hard when you see [young protesters] playing their drums, holding their signs,” she says.

Her daughter gave her tips in case of any violence, and they stayed together the entire march.

“There’s a lot of older folks who really want to leave a better country for their children, and a lot of children … telling their grandparents ‘Look, you have to march because of the environment or because of pension reform or health care reform,’” says Mr. Guzmán. “These protests have brought together a very diverse cast of characters that makes a formidable opposition to the government.”

The recent surge in protests is a continuation of what began pre-pandemic, in 2019. Tax reform wasn’t on the table, but frustration with government services and inequality was already festering. Now discontent is far more widespread, says Elizabeth Dickinson, a senior analyst with the International Crisis Group.

“Grievances run a lot deeper,” Ms. Dickinson says. “Fundamentally it’s about … a feeling among many people that it’s impossible to have any social mobility and that’s because of the way the access to education and the labor market works.”

The police clampdown has garnered demands for a security overhaul. Colombia’s police, which report directly to the Ministry of Defense, are trained to deal with guerrilla warfare due to the country’s five-decade armed conflict. Since the 2016 peace accord, many question whether the country still needs such an aggressive police force.

“We have a security force that is used to looking for an enemy from within, looking for guerrilla forces, and so when you have peaceful protesters on the street, the way they feel they’re being treated is as if the security forces are at war with them,” Ms. Dickinson says.

For Mr. Camargo, the protests must go on “until something is achieved,” despite the violence.

He has a message for his president, who he says “has to listen.”

“Put yourself in the shoes of working-class people. ... You have everything and there are some people who have absolutely nothing,” he says. “While people continue to go hungry, while there’s so much inequality, there will never be peace in Colombia.”

Interview

One of NASA’s ‘hidden figures’ writes her own story

NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson’s memoir offers a glimpse into how she found success amid the racism and sexism of her era. The Monitor spoke with one of her daughters, Joylette Goble Hylick, about her late mother’s outlook – and how she finally got to space.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Randy Dotinga Correspondent

Katherine Johnson, a member of a team of Black female mathematicians at NASA, was crucial to the United States’ success in space exploration, though for years her contributions were little known. While the book and movie “Hidden Figures” catapulted her and her teammates to the recognition they long deserved, Ms. Johnson felt there was still more to tell. So, assisted by her two daughters, she wrote a memoir that was recently posthumously released.

Late in life, about her newfound fame, she said, “I was just doing my job, and I don’t know what all this is about,” recalls her daughter Joylette Goble Hylick in an interview. But while fame wasn’t Ms. Johnson’s goal, it’s allowed more people to learn about her story – not just about her grit and determination in overcoming sexism and racism, but also about the ideals of humility and respect she passed down to her family along the way.

One of NASA’s ‘hidden figures’ writes her own story

Five years ago, a bestselling book and then an acclaimed film introduced the world to the “Hidden Figures,” a group of Black female mathematicians who played crucial roles at NASA during the Cold War space race. Research scientist Katherine Johnson, whose calculations were critical to major missions, became a hero to millions. Ms. Johnson, a centenarian who died in 2020, wrote about her life for the new memoir “My Remarkable Journey,” with help from her two daughters, Joylette Goble Hylick and Katherine Moore. Ms. Hylick spoke with the Monitor recently.

Q: What did your mother think when she became famous?

She’d say, “I was just doing my job, and I don’t know what all this is about.” Those ladies didn’t do their work to get famous. They did it because they could, because it was challenging, because they felt they were representing our community. And especially because they knew we were in a race against the Russians in the early years of the space program. They had a duty to their country.

Q: How did she deal with obstacles like racism and sexism?

The barriers she had, the hiccups and trauma that she lived through the course of her entire life? She just seemed never to let them bother her. She would not ignore them, and she didn’t cower. But she’d figure out how she could get what she wanted in spite of it. Her attitude was “Oh, well, if I can’t do it this way, I’ll do it that way.” I was in college during a time where you had lunch-counter demonstrations [against segregation]. She didn’t want us to get involved because we could get hurt and because, as she told me, if you want to work at NASA, you can’t have a record. Her message was: Do it another way, demonstrate another way.

Q: How did she develop her blend of resilience and generosity?

She wasn’t intimidated, but she also didn’t look down on people. I give all credit to my granddad. We kept saying we’ve got to write a book because we want people to know him. Granddaddy told her when she was little that “nobody in this town is better than you are, and you are no better than anybody in this town.” You’ve got too many people out here who’ve got to have someone to look down on. Why? Why would you be more important than me? You breathe, and I breathe. You work, and I work.

Q: Do you think she found the balance between being aggressive and being assertive?

Yes. She was assertive but not aggressive. She believed that if you’re aggressive, you won’t get as far because you’re going to get a counterreaction. I can’t remember seeing her just boiling mad unless it was about something somebody did that didn’t make sense.

Q: How did she develop an interest in mathematics and numbers?

They say she started counting on Day 1. She counted everything: the stars, dishes and silverware, steps. She had a fascination with numbers.

Q: What can we learn from her?

Her philosophies were to be prepared, love what you’re doing, follow your passion, and do your best. You’d never hear her say anybody told her that. She just knew it, and she did what she expected us to do. It wasn’t a teaching thing. It’s about watching: She understood that kids do what you do quicker than what you say. She also said to find out what it is you’d like to do. If you work hard at it, it won’t be a job. She said she never worked a day in her life at NASA. She loved it because as soon as one thing was finished, they would be on to something else.

Q: Did she like being a celebrity late in life?

The highlight of her career was meeting President Barack Obama. She’d always say, “He kissed me on my cheek!”

Q: Did she want to go to space herself?

[An astronaut friend] was working on a project to go to Mars and asked, “Would you like to go with me?” Mom said she would in a heartbeat. This year, Northrop Grumman [an aerospace company] named a spacecraft after her. They put a photo of her on a flag so that when the spacecraft attached to the International Space Station [to provide supplies], the first thing the astronauts would see would be this picture of her. When they asked me what I thought, I cried. She got to go to space anyway!

With giant trolls, one artist preserves imagination – and the environment

How can having a childlike view of the world help the environment? Danish eco-artist Thomas Dambo combines a flair for recycling with a fairy-tale imagination to bring people worldwide closer to nature.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A group of new residents arrived recently in Boothbay, Maine. Among them is a wizened troll named Birk, who sports a beard made from the roots of fallen trees, and Røskva, whose thatched fur is made from tiles of bark.

These giants, the work of Danish eco-artist Thomas Dambo, were commissioned by Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens as part of a new exhibition, “Guardians of the Seeds.” The goal is to give visitors an emotional connection with nature that will encourage them to become stewards of it.

Since 2014, Mr. Dambo has built unique trolls across the world, including in China, South Korea, and Puerto Rico. Each one is constructed from recycled materials. “I like showing people that trash doesn’t need to be a bad thing. It can be a beautiful thing,” he says in an interview.

On a recent visit to the gardens in Maine, it starts to rain on Shaad and Andrea Breau and their daughter, Eidi, while they admire Røskva. They take shelter beneath the statue’s vast girth.

“Thankfully, this troll was here to protect us,” Ms. Breau says to kindergarten-aged Eidi, as she clambers over the tennis racket-sized toenails. The girl gazes up and yells, “Thanks, troll!”

With giant trolls, one artist preserves imagination – and the environment

Call it a troll safari. In the woods of Maine, a family of three is searching for creatures from Scandinavian folklore. Shaad and Andrea Breau survey a trail map as their young daughter, Eidi, bounds ahead of them. They won’t need binoculars to spot the trolls. This species would dwarf a Mack truck.

“Look, Mama,” exclaims Eidi, pointing at a 20-foot-tall wood sculpture of a troll looming between several pines. It’s like a scene out of Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are.”

“Is it made out of a tree?” asks Eidi.

Danish eco-artist Thomas Dambo built the spiky-haired troll, named Røskva, from discarded scraps of wood. It’s one of five trolls commissioned by Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens for its 323 acres of resplendent riverside woodland. The “Guardians of the Seeds” exhibition aims to give visitors an emotional connection with nature that will encourage them to become stewards of it.

Since 2014, Mr. Dambo has built dozens of unique trolls across the world, including in China, South Korea, and Puerto Rico. Each one is constructed from recycled materials from scrap yards and dumpsters. The key quality of his work? Its playfulness. For example, one of his trolls in Denmark sits astride a real car on a hillside, appearing to gleefully ride it like a sled. Mr. Dambo wants to reactivate a childlike imagination in adults so they begin to see trash as objects that can be repurposed in practical and even picturesque ways. And, yes, he loves to entertain kids, too.

“Thomas’ origin story is about being a kid and riding his bike, climbing trees, and scavenging for materials to build treehouses,” says Angela Del Monte, a graduate of the Copenhagen Business School who spent time with the artist for her 2020 master’s degree thesis, “Playing to His Strengths: A Case Study of Artist Entrepreneur Thomas Dambo.” “Thomas said he never stopped playing,” she adds.

But Mr. Dambo also discovered early on that some adults intrude on the world that children dream up. A schoolteacher once punished him for sitting in a window frame and gazing outside. He was forced to sit underneath the teacher’s table for the duration of a class. When Mr. Dambo’s mother heard about what happened, she transferred her son to a “hippie” school in the countryside. The boy quickly found a kindred spirit in one of his new teachers, Mogens Sigsgaard-Rasmussen.

“He would always sit up in the tree during classes and read us fairy tales,” recalls Mr. Dambo in a phone interview from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where he’s building his 81st troll. “We would only spend two-thirds of the time doing school stuff. But we did a lot of learning by doing, so we would go out to build stuff out of wood.”

At lunchtime, Mr. Sigsgaard-Rasmussen would pass around a tray to collect all the scraps of food that fussy children didn’t want to eat because they thought it looked funny. Then he’d make a show of enjoying leftovers such as sandwiches filled with stinky cheese.

“He would also show us there was nothing wrong with the cheese,” recalls the artist. “One child would be afraid that another child would think that there is something wrong with me if I eat the cheese, because somebody else might say, ‘It’s smelly.’ So the reason I like this story is, of course, because it’s touching on a lot of the issues that we have with our trash and our recycling.”

Nowadays, Mr. Dambo relishes dumpster diving. In 2018, for instance, he visited several recycling plants in Mexico City to find stuff he could refashion into a plastic botanical garden called “The Future Forest.”

“I like showing people that trash doesn’t need to be a bad thing. It can be a beautiful thing,” he says. “I think that will solve a lot of our problems if we could just share things more and don’t only think that new objects are good objects.”

To challenge himself creatively, the artist allows for a degree of improvisation on-site. For “Guardians of the Seeds,” he gave a wizened troll named Birk a beard made from the roots of fallen trees. Røskva’s thatched fur is made from tiles of bark. Gro, who sits with her eyes closed in a serene yoga pose, has a copper tongue made out of a planter.

The artist came up with a story that this family of trolls hid 10 golden seeds to protect the old forest. Using a map that’s provided, visitors follow clues to find a secret place where those seeds are hidden.

“Thomas wants people to interact with these trolls,” says Gretchen Ostherr, president and chief executive officer of Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens. “He really wants it to be a journey of discovery where you’re walking along and all of a sudden this big magical being appears in front of you. These are friendly, happy trolls. They’re not scary, mean trolls under a bridge or on the internet.”

The Danish artisan hopes that “Guardians of the Seeds” gives viewers the same joy he gets from an occupation that he compares to a hobby. He says too many people lose their playfulness in the rough-and-tumble treadmill of adult life.

The Breau family, local members of the gardens, say they’d wanted to join the 150 volunteers who helped Mr. Dambo erect the trolls. But it didn’t work out. While they’re admiring Røskva, it starts to rain. They take shelter by dashing beneath the wooden statue’s vast girth.

“Thankfully, this troll was here to protect us,” Ms. Breau says to kindergarten-aged Eidi, who is clambering over Røskva’s tennis racket-sized toenails. The girl gazes up and yells, “Thanks, troll!”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Egypt the calm-maker

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In the Middle East, where trusted mediators are hard to find, Egypt has received high praise for negotiating a truce Thursday between Israel and Hamas, ending 11 days of war that took the lives of hundreds of civilians. Unlike neutral brokers such as those from the United Nations, however, Egypt is driven largely by its own need for calm in mediating between Israelis and Palestinians. It borders both Gaza and Israel and cannot afford spillover effects from the frequent wars between them.

Despite this self-interest, Egypt has over time developed better mediation skills, perhaps accounting for a shorter war between Israel and Hamas this time than the last one in 2014, which lasted seven weeks.

For all its faults in suppressing dissent at home, the Sisi regime in Cairo is one of the few governments in the region playing peacemaker. Oman and Iraq often play a similar role. Leaders in all three have adapted the mediator’s touch – listen first and then find common ground. Sometimes that results only in a truce, perhaps a temporary one, as with Israel and Hamas. But calm can be a good start for peace.

Egypt the calm-maker

In the Middle East, where trusted mediators are hard to find, Egypt has received high praise for negotiating a truce Thursday between Israel and Hamas, ending 11 days of war that took the lives of hundreds of civilians.

Germany said Cairo was a “very, very important quantity” in the cease-fire. France said it was “absolutely key.” The United Nations commended Egypt, while President Joe Biden, who had been giving a cold shoulder to Egypt’s authoritarian ruler, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, finally called him Thursday. One U.S. official described Egypt as “the main game in town.”

Unlike neutral brokers such as those from the U.N., Egypt’s mediation between Israelis and Palestinians is driven largely by its own need for calm. It borders both Gaza and Israel and cannot afford spillover effects from the frequent wars between them. Egypt also needs good ties with Israel to continue massive financial aid from the U.S., and it wants to contain Gaza’s rulers, Hamas, who are allies of the Muslim Brotherhood, a political Islamic movement banned in Egypt.

Despite this self-interest, Egypt has over time developed better mediation skills, perhaps accounting for a shorter war between Israel and Hamas this time than the last one in 2014, which lasted seven weeks. Cairo has begun to mediate in other regional conflicts. Its envoys recently helped calm Libya’s conflict and have sought a role in Syria’s ongoing war. And it remains a mediator between the two main Palestinian factions: Fatah in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza.

As the world’s oldest country, Egypt has tried to make peace between Israel, which was created in 1948, and Palestine, a country that does not exist as a normal state. But it has been unable to bridge the ideological divide between them.

For all its faults in suppressing dissent at home, the Sisi regime in Cairo is one of the few governments in the region playing peacemaker. Oman and Iraq often play a similar role. Leaders in all three have adopted the mediator’s touch – listen first and then find common ground. Sometimes that results only in a truce, perhaps a temporary one, as with Israel and Hamas. But calm can be a good start for peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The antidote for defensiveness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kathryn Jones Dunton

What can we do when offense and anger, rather than humility and thoughtfulness, characterize our response to criticism? Considering our nature as God’s children is a valuable starting point for progress, as a woman who was prone to defensiveness experienced.

The antidote for defensiveness

“You know, you are overly defensive,” a friend gently told me. I quickly retorted, “No, I’m not!” And then we both laughed because my response clearly illustrated that there was some truth to his accusation. My friend wasn’t wrong – I liked to think of myself as humanly perfect and expected everyone else to see me that way, too. I tended to feel offended and angry when confronted with criticism, which would often lead me to react defensively.

This kind of defensiveness stems from a perceived threat to one’s mortal sense of selfhood. I have since learned that there’s an antidote to this. Through my study of Christian Science, I’ve learned the distinction between a mortal concept of ourselves and our true, spiritual identity. As the spiritual reflection of the perfect God, divine Spirit, each of us is in truth flawless. But our human expression of that spiritual perfection is a work in progress!

To grow spiritually and better demonstrate our God-given perfection, we need to honestly examine our thoughts and actions. For instance, when considering how to respond to something that’s been said, I’ve found it helpful to ask myself, “Am I truly expressing the Christ-spirit – letting God, Love, guide me in how I respond?” In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes, “Honesty is spiritual power” (p. 453). A willingness to really examine ourselves allows us to see what unhelpful traits we need to relinquish – to detect error in our thought in order to eradicate it.

These ideas have helped me be better about humbly asking for God’s guidance in expressing true love and Christliness in the face of criticism, rather than stubbornly thinking, “I am perfect! Why can’t they see it?”

Although defensiveness is detrimental to our spiritual progress, it is important to defend ourselves spiritually. Spiritual defense consists of really feeling and knowing that we are God’s precious, perfect spiritual ideas.

As we really get to know ourselves in this light, the pull of irrational defensiveness falls away. We realize that we are already preapproved of God, a realization that empowers us to better live up to that – including being humble enough to consider whether there is merit in a critical comment someone may offer. If there is, we can change our thoughts and behavior. If there is not, we can let the criticism go with love and forgiveness, and move on.

I had an opportunity to put this into practice when I was elected to the office of Reader in my local branch Church of Christ, Scientist. Everyone was usually very supportive and encouraging. Once in a while a member would offer critical advice. Through prayer I was impelled to lovingly respond, “Thank you for bringing that to my attention,” rather than reacting defensively in those situations. I would then pray deeply about the comment. Humbly listening for God’s direction always helped me to see whether I needed to make a change or not, and to willingly and lovingly follow God’s guidance.

Each of us can nurture a willingness to examine our thought to bring it into line with God’s direction and with our nature as God’s children. This is the antidote to defensiveness.

A message of love

An artful leap

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come again Monday, when our reporters in Jordan and the West Bank explore how young Palestinians use TikTok and other social media to advance their cause – without political leadership.

And in the meantime, remember that the First Look section of our website features additional news coverage including on this week’s Israel-Gaza cease-fire.