- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Grappling with the classics – elitist or universal?

Should colleges teach the classics? To some, the Greek and Roman canon is for elitists whose idea of small talk at Yale dinner parties is to quote Pliny the Younger in Latin.

But for Anika Prather, these ancient works are vital to understanding Black history. That’s why she’s dismayed that Howard University, where she’s an adjunct professor, is dissolving the classics department and dispersing some of its courses to other divisions. The historically Black university says it’s resetting priorities as student demand for the classics dwindles. At the same time, some worry that the texts are an intellectual bulwark for white supremacy.

But Dr. Prather says, “The issue is not classics. ... The issue is how people teach them.”

Her course at Howard, Blacks in Classical Studies, reveals that diversity was always in the original texts – from Terence, the Roman African playwright, to the multicultural influence of Ethiopians and Egyptians on Plutarch and Herodotus. Her course also traces how the classics influenced Frederick Douglass, Anna J. Cooper, Martin Luther King Jr., and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Any ethnic group can claim that the classics are all about them, she adds. But then they miss the broader view: The classics encompass all of us. The search for beauty, truth, and virtue isn’t elitist – it’s universal.

When Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton read Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” it made him want to free Black people, Dr. Prather says. But then she goes even further: “We all need to be set free. White people, Black people. I want us all to come out of our caves and look at each other in the light and see our common humanity.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

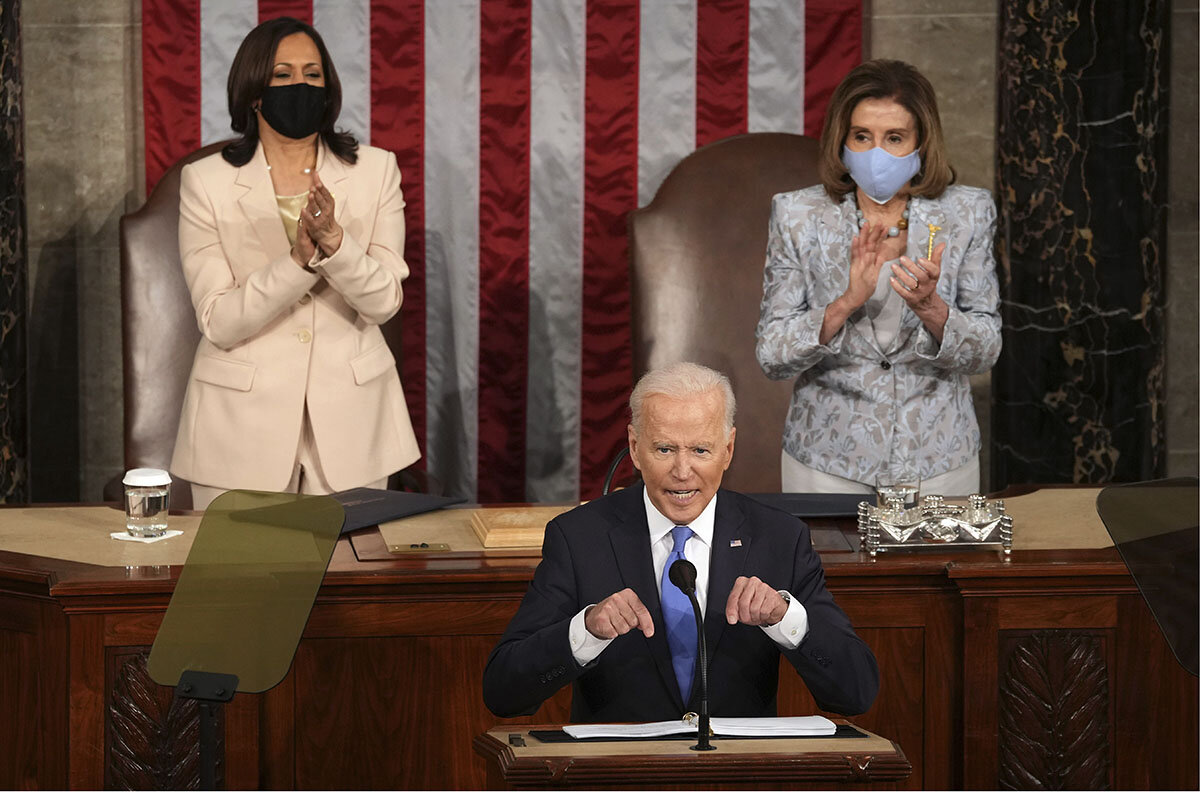

Biden’s first 100 days: Promises kept, but challenges loom

So far, President Biden has followed through on a number of campaign promises – particularly on the pandemic. But he’s gotten relatively few bills through Congress, and the path ahead is likely to grow tougher.

Joe Biden vowed that, in his first 100 days as president, controlling the COVID-19 pandemic would be a top priority. As he passes that marker on Thursday, the United States seems on the verge of doing so, following the government’s efforts to tamp down infection rates while pushing mass vaccination.

Congress passed Mr. Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill in March, sending direct payments to voters while extending unemployment aid and a moratorium on evictions. The president has also fulfilled promises to reverse a number of former President Donald Trump’s executive actions, including rejoining the Paris climate agreement and ending the travel ban on a number of majority-Muslim countries.

Whether Mr. Biden can push through ambitious items such as his massive infrastructure bill remains to be seen. His immigration policy is in turmoil as a surge of unauthorized migrants has swamped the border.

But Mr. Biden’s first 100 days have signaled his vision for his time in office, centered on his belief that the federal government has an active role to play in Americans’ lives.

“His belief in government is going to continue to be an essential part of what the Biden administration is all about,” says Julian Zelizer, a political history professor at Princeton University.

Biden’s first 100 days: Promises kept, but challenges loom

Thursday marks President Joe Biden’s 100th day in office, a traditional milestone that he and his team have been aiming toward since he won the Democratic nomination, if not before.

It’s an arbitrary point at which to sum up how a new U.S. chief executive is doing. But the media has closely followed presidents’ first 100 days for almost a century, judging promises kept or broken, and what that may mean for the many hundreds of days left in a presidential term.

As a candidate, Mr. Biden vowed that controlling the COVID-19 pandemic would be a top priority. The United States seems on the verge of doing so, as the administration has promoted efforts to tamp down infection rates while pushing mass vaccination.

Congress passed Mr. Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill in March, sending direct payments to voters while extending unemployment aid and a moratorium on evictions. The president has fulfilled promises to reverse a number of former President Donald Trump’s executive actions, including rescinding the Keystone oil pipeline permit, rejoining the Paris climate agreement, and ending the travel ban on people from a number of majority-Muslim countries.

Whether Mr. Biden can push through ambitious pending items such as his massive infrastructure bill remains to be seen. His immigration policy is in turmoil as a surge of unauthorized migrants has swamped the border.

But if nothing else, Mr. Biden’s first 100 days have signaled his vision for his time in office, centered on his belief that the federal government has an active role to play in Americans’ lives.

“[Mr. Biden] may find himself more checked as we go on, but his belief in government is going to continue to be an essential part of what the Biden administration is all about,” says Julian Zelizer, a political history professor at Princeton University. “He is going to continue to rely on the government as a tool rather than a problem.”

Big spending

To this point, Mr. Biden’s presidency has revolved around government spending, actual and proposed. His COVID-19 relief bill authorized direct government checks for many Americans. In a speech to a joint session of Congress on Wednesday night, he outlined a $1.9 trillion, 10-year proposal for aid to workers, families, and children – on top of the trillions for infrastructure spending he requested in March.

Public judgment of Mr. Biden’s first 100 days has been mixed, but generally positive.

Unlike most new presidents, he has not benefited from much of a honeymoon period, as his job approval rating at this point is lower than that of any newly elected president going back to Dwight D. Eisenhower, with one exception – his predecessor. President Trump’s job approval number at 100 days was just 42%, according to the FiveThirtyEight poll averages, while Mr. Biden’s is above water at 54%. (Gerald Ford’s approval rating was also lower than Mr. Biden’s at 100 days, but he was an unelected president, and unpopular at the time due to his pardon of Richard Nixon.)

Mr. Biden has been buoyed by good numbers on particular issues. A Reuters/Ipsos poll from mid-April found that 65% of Americans approve of the way he has handled the coronavirus, and a majority approve of how he has handled jobs, the economy, and unifying the country.

These numbers may reflect the campaign promises he has followed through on, including:

- Rejoining the World Health Organization and the Paris climate accord on his first day in office. He also reversed Mr. Trump’s ban on transgender Americans serving in the military, as well as Mr. Trump’s travel ban aimed at some majority-Muslim countries.

- Extending a pause on student loan payments and housing evictions and foreclosures.

- Vaccinating more than 200 million Americans over the past three months, surpassing the goal of 100 million.

- Convening a world climate summit and pledging to cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% by 2030.

- Creating a task force to help reunite the hundreds of immigrant children separated from their parents.

- Sending a bill to Congress to provide a pathway to citizenship for America’s 11 million unauthorized immigrants (although the bill has not passed).

- Announcing U.S. withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan by Sept. 11, 2021.

- Slapping new sanctions on Russia in response to cyber intrusions and efforts at 2020 election interference.

Why use 100 days as the benchmark? Why not 50 – or 365? To administration staffers, the made-up nature and media hype of the moment can be frustrating. David Axelrod, senior adviser to former President Barack Obama, once called the 100th day the “journalistic equivalent of a Hallmark holiday.”

But it does have historical roots. Shortly after being sworn in as president amid the Great Depression in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt unleashed a burst of action to try to rally a demoralized nation. It included creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps, passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act, the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority, and other actions to build the core of what became the New Deal. It was the first of the first 100 days.

Ever since, presidents have been measured against that activist beginning.

“[The 100-day mark] has become an initial judgment on the presidency. If it’s good, it’s going to help him in his next year. If it’s bad, it will hinder him,” says Elaine Kamarck, director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Effective Public Management. “It’s somewhere in between a Hallmark holiday and something important.”

Still, a president’s first three months don’t necessarily reflect how the president’s term will be remembered years later. President Jimmy Carter, for example, was largely considered to have had a successful first 100 days, but went on to lose reelection. And while the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion occurred during President John F. Kennedy’s first 100 days, his presidency is mostly remembered fondly.

Many presidents’ signature achievements, such as President Obama’s health care reform and President Bill Clinton’s balancing of the federal budget, come after their first 100 days.

“You read all these newspaper articles and it’s like, ‘Here is the president’s report card.’ I mean, I don’t grade my students after 100 days,” says Sidney Milkis, a professor at the University of Virginia and an expert on the American presidency.

“I don’t think there is any strong relationship between how you do in your first 100 days and what you achieve in your presidency,” adds Mr. Milkis. “It’s a benchmark that got established because of its extraordinary importance during [FDR’s tenure].”

Few bills passed

One metric in which President Biden has so far fallen short is passage of legislation. His COVID-19 relief bill was indeed historic in size and rated as popular in polls, but it wasn’t part of a deluge. According to GovTrack, only seven laws have been enacted thus far in Mr. Biden’s term – a fraction of what’s been passed in the first 100 days historically. FDR had 76 bills passed into law during this time, and Mr. Biden’s immediate predecessors, Mr. Obama and Mr. Trump, had 14 and 30, respectively.

Mr. Biden has plans to change this. He’s proposing spending bills so big they might rewrite the role of the government in the U.S., including a $2.3 trillion infrastructure bill outlined in March, and $1.8 trillion in spending and tax cuts over 10 years for workers, families, and children, as announced in Wednesday night’s speech.

But Mr. Biden faces a very different political landscape than did his two most recent predecessors or Roosevelt. They all enjoyed wide party majorities in both houses of Congress. Mr. Biden has the slimmest House majority in modern history, while Vice President Kamala Harris has already cast four tiebreaking votes in the Senate, a record this early in a presidency.

And legislating will likely only get harder for Mr. Biden as his term goes on. It could screech to a virtual halt if Republicans make big enough gains in the 2022 midterm elections to take back one or both congressional chambers.

“The worst enemy of good legislating is time,” says Joel Payne, a Democratic strategist who worked in former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s office as the negotiations for the 2010 health care reform bill were dragged out. “The more time you lose, the more leverage you lose – and all of this is in the back of the head of the Biden team.”

This worry may rise as the Biden administration considers its promises for the first 100 days that were not completed:

- Opening the majority of U.S. public schools that have been closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Reversal of Mr. Trump’s corporate tax cut.

- Enactment of the Equality Act to ensure equal rights for LGBTQ Americans and direct federal resources to help prevent violence against transgender women.

- Ordering of an FBI report on how to ensure background checks are completed for gun purchases.

- Extension of the Voting Rights Act.

- Passage of the Safe, Accountable, Fair, and Effective Justice Act.

- Provision of resources for asylum-seekers and for reforming the asylum system.

- Convening of a regional meeting with leaders from Mexico, Canada, and Central America to address migration and propose solutions.

- Ending long-term detention centers and raising the refugee cap to 125,000 from the 15,000 limit set by Mr. Trump.

Some of Mr. Biden’s lowest approval ratings are in response to how he has handled immigration. Most experts agree addressing the status of the U.S.-Mexico border will be the next big hurdle for Mr. Biden and will influence how his administration is remembered after the first 100 days.

Foreign policy also remains a work in progress, in part because it is an area where there are not always easily discernible gains. The Biden administration is committed to resuming a multinational deal limiting Iran’s nuclear program, for instance, but that remains far from a done deal. And managing relations with China, which involves courting Beijing on some issues and confronting it on a range of others – including its repressive actions in Hong Kong – will be a difficult task for however long Mr. Biden remains in office.

“He’s off to a good start,” says Mr. Milkis, “but there are treacherous waters ahead.”

Meet the gun owners who support (some) gun control

Contrary to popular myth, gun owners aren’t a monolithic group with views that closely mirror those of the NRA. In some suburban areas, diverse firearm owners are seeking solutions to gun violence, from personal responsibility to some regulation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Jeff Kelman grew up in a progressive Massachusetts home, the son of two mothers. He had no idea people could even own guns until he was in middle school. But after college, he started shooting for sport – and developed a sharp eye.

As a Jewish man whose wife is Chinese American, he is keenly aware of racial discrimination, and the potential for that to turn into violence. So, he carries a gun for self-defense.

Like other suburban gun owners, he is open to at least some regulation, particularly focused on gun safety.

In 2020, the United States saw the largest number of gun-related deaths – 19,000 – in almost two decades. This spring has also seen a resurgence of mass shootings (defined as four or more people killed), which had paused during pandemic lockdowns.

In response, the Democratic-led House passed legislation that would require background checks for all gun buyers and extend the time the FBI has to conduct those checks. A majority of gun owners support both ideas. The bill’s future in a 50-50 Senate is uncertain at best.

Whether the engagement of suburban gun owners like Mr. Kelman is enough to break gridlock in Washington is far from certain. Guns, after all, are deeply embedded in America’s polarized identity politics.

Meet the gun owners who support (some) gun control

George Cook had never thought much about guns until about four years ago. Then he grew older and got married, and felt like he had a lot more to protect.

So he bought a handgun. And last year, at the height of social justice protests and scattered violence, he bought an AR-15. During the pandemic, first-time gun owners spurred record levels of gun sales for what looks like the second year in a row, with uncertainty, political polarization, and a spike in shootings around the country cited as reasons for the buying spree.

Today, Mr. Cook goes a few times a year to the range to shoot his firearms. Aside from that, neither weapon ever leaves his house. He figures about half the houses on his street on the Richmond, Virginia, outskirts have guns in them. He cites suburban values as one reason he bought a gun.

“It’s easy to measure how bad guns can be for sure,” says Mr. Cook, who works as a corporate treasury analyst. “You can look at all the deaths, the mass shootings. But it’s not easy to measure the bad that they prevented.”

Those values are notable in another way: Like other suburban gun owners, Mr. Cook says he is open to at least some regulation, particularly those focused on gun safety. Interviews with suburban gun owners underscore how U.S. gun culture is becoming more diverse, more nuanced, and increasingly focused on the personal responsibility of individuals who choose to own a gun.

In 2020, the U.S. saw the largest number of gun-related deaths – 19,000 – in almost two decades. This spring has also seen a resurgence of mass shootings (defined as four or more people killed), which had paused during pandemic lockdowns: The March 16 mass shooting in Atlanta, where eight people were killed, was followed quickly by three more, including in a Boulder, Colorado, supermarket and an Indianapolis FedEx facility.

On March 11, the Democratic-led House passed legislation that would require background checks for all gun buyers and extend the time that the FBI has to conduct those checks. A majority of gun owners support both ideas. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has vowed to bring a package to the Senate as early as May, but Republican support is considered unlikely.

Whether the engagement of suburban gun owners like Mr. Cook in the debate over gun safety is enough to break gridlock in Washington is far from certain. Guns, after all, are deeply embedded in America’s polarized identity politics.

But the emerging focus on gun safety “is really an important effort,” says Adam Winkler, author of “Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America.” “We can talk about gun control and gun regulation until we’re blue in the face, but there’s always going to be a lot of guns in America. They are here to stay. ... [But] many of our gun problems can be lessened or reduced by responsible gun ownership.”

Changing portrait of the American gun owner

The image of a typical gun owner is a white man, usually conservative, who lives in the country.

Yet most American adults have shot a gun at least once: 72%, Pew found in 2017. And nearly half of all non-gun owners said they would consider owning a gun in the future.

Increasingly gun owners are represented by more suburban groups like the Pink Pistols, Liberal Gun Owners, and blogs like Gun Culture 2.0, run by a gun-toting college professor in North Carolina. Polls have found that a majority of gun owners favor stronger gun regulations, as long as the basic right of gun ownership is respected.

Part of the reason is that suburban Americans who used to never think about gun violence are now thinking about it “too much,” as one suburban woman told the Cook Political Report in a wide-ranging focus group last year. Yet for many of those worried about violence, the answer isn’t necessarily fewer guns.

Dan Gross has long understood that paradox. His brother was shot in the head and permanently disabled in a mass shooting at the Empire State Building in 1997. The former head of the Brady Campaign has worked for years to enact stronger gun laws, but always, he says, with a sense of empathy for law-abiding gun owners.

He says his support for gun ownership hasn’t changed – he’s just become more outspoken on how to actually reduce gun violence. He has criticized President Joe Biden for calling for an assault weapons ban, given that it only riles up Second Amendment supporters and, more importantly, fails to acknowledge that assault rifles are rarely used in homicides. Just 1% of gun-related deaths are “active shooter” situations, compared with 30% that are homicides. Instead of trying to ban certain guns from all people, he says the focus should be on how to keep all guns away from certain people, such as stronger red flag and background check laws.

Meaningful change, says Mr. Gross, means changing the entire conversation from one defined by politics to one defined by common values and goals, specifically, protecting the community. Speaking in front of a potentially unfriendly Second Amendment rally in Washington, D.C., in 2019, he saw evidence that it could work.

“I start to get momentum and people are applauding ...,” says Mr. Gross. “And there’s a guy toward the front, and he was the one guy that, [stereotypically] if I should be scared of someone, it’s that person. And when I said, ‘Now, we may not agree on everything,’ that’s the guy who screams out: ‘That’s OK!’”

Respect and responsibility

A focus on respect and responsibility rings true to Jeff Kelman of New Hampshire.

Mr. Kelman grew up in a progressive Massachusetts home, the son of two mothers. He had no idea people could even own guns until he was in middle school. But after college, he started shooting for sport – and developed a sharp eye.

As a Jewish man whose wife is Chinese American, he is keenly aware of racial discrimination in the U.S., and the potential for that to turn into violence. So, he carries a gun for self-defense.

Instead of lining up his views ideologically, Mr. Kelman prefers to approach the issue as a cost-benefit analysis. Gun control laws have the potential to save lives, but also come at the cost of personal freedom. In that analysis, everyone has a different threshold.

“If you’re going to have an armed society, you almost need to have a ubiquitously armed society,” he says. “Alternatively, if you have a society that isn’t going to take up this act and they’re going to delegate that to the police and the military ... then again, both of those societies will be, I think broadly, fairly safe.”

The more it becomes a “patchwork,” he says, the less it makes sense.

A pragmatic approach

Some sense that suburban gun owners present a unique opportunity for pragmatic change. Nestled between rural areas where lots of people hunt and cities where most gun violence occurs, the suburbs offer a sense that “the old patterns or the old methods aren’t working very well,” and a growing frustration that “we’re not getting anywhere in the gun violence prevention debate right now,” says Professor Winkler at the University of California, Los Angeles.

But others think their overall influence would be marginal, at best.

“It’s not clear, as a separate political force, how much impact [suburban gun owners] would have outside of a ticking up in public opinion polls support for stronger gun laws,” says Robert Spitzer, author of “The Politics of Gun Control.”

Anecdotally at least, Tom O’Connor, who sits on the board of Gun Owners for Responsible Ownership, finds gun owners in those expanding areas more pragmatic than traditional gun owners. That expresses itself, he says, in their support for universal background checks, red flag laws, and requirements for safe storage.

Rights, after all, change over time, says Mr. O’Connor. And if the public doesn’t support absolute access to firearms, that access could be curtailed. “It’s clearly something we have to deal with,” he says.

Mr. Cook, the Richmond suburbanite, says values, culture, and identity complicate the search for compromise. After all, he says, people use guns in so many different ways across the U.S., whether for hunting, sharp-shooting, or protection.

Yet he has felt his own attitudes shift. “The more things [like mass shootings] happen, the more my views change,” he says. “I’m not set in stone in my ways. I still think guns should be legal, and yet I’m definitely deeply affected by this. It makes me second-guess myself.”

Editor's note: A clarification has been made indicating that Jeff Kelman began shooting for sport after college. The timing of the House passage of legislation relating to background checks has also been clarified.

Are talks with Sahel extremists taboo or a path toward peace?

In negotiations with Islamists in West Africa, a prerequisite to cease-fires may be to establish trust. Some who advocate local talks see signs of hope – but can such talks really serve justice?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The Sahel is awash in jihadi insurgencies. From Nigeria to Mali, the stakes are high. About a million people have been displaced by conflict in Burkina Faso alone, where hundreds of people have died.

But is negotiating with militants part of the answer, or a serious misstep? A short-lived truce in Burkina Faso and a handful of other local talks highlight a debate about whether government officials or local leaders should pursue talks for peace.

In Burkina Faso, some critics firmly oppose negotiations on principle – including Albert Ouedraogo, a former minister of education. “The government’s line is to refuse any dialogue with those who sow death – I stick to this posture,” he writes over a WhatsApp interview. “Who will compensate the victims and [punish those who] have sown terror?”

Others say dialogue could sow seeds of stability across the region. Boubacar Ba, of the Bamako-based Analysis Centre on Governance and Security in the Sahel, harbors hope. He saw for himself how much a negotiated peace meant to Malian locals, even if no one was held to account for the violence perpetrated.

“They also recognize that the road to peace is long and difficult,” he says. “It is a beginning and we must believe in it.”

Are talks with Sahel extremists taboo or a path toward peace?

In once-peaceful Burkina Faso, it was Djibo that first fell.

The jihadi insurgency currently engulfing the country originally spread from neighboring Mali, where groups backed by Al Qaeda and the Islamic State have operated for almost a decade. But homegrown Islamist movements soon sprung up.

And the provincial capital of Djibo itself, near the border, was home to one Malam Ibrahim Dicko, a radical preacher calling on the region to rise up against the government, which he accused of neglecting the north.

So last November, after five years of bloodshed, Djibo’s residents welcomed an odd development. The number of jihadi attacks was falling considerably, and some of the town’s men who had joined Islamist groups returned – the result of secret peace talks between jihadis and government officials, as reported by the New Humanitarian.

Today, the fragile cease-fire appears to have broken down. Attacks are creeping back up in Djibo, the capital of northern Soum province. The violence has been like a wave, according to Oumar Zombre, a journalist with Radio Télévision du Burkina in the country’s capital, Ouagadougou. “There are sporadic attacks,” he says. “It gets calm and then it gets hot again.”

But the short-lived truce highlights a broader debate in West Africa’s troubled Sahel, where local and foreign troops are battling Islamic insurgencies. Can these types of negotiations lead to more permanent cease-fires? Should government officials or local leaders negotiate with insurrectionary Islamists for peace in the first place – and if so, how?

The stakes are high. In Burkina Faso alone, jihadi violence has left hundreds of people dead since 2016, and about a million displaced – that number multiplying tenfold from 2019 to 2020. France has deployed troops to the region, as has United Nations peacekeeping force MINUSMA, and the G5 Sahel, an alliance of security forces from Mauritania, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali.

Burkinabé conflict analyst Mahamoudou Savadogo, of Senegal’s Université Gaston Berger, says the shaky peace in Soum likely failed because the government did not initiate a clear reintegration plan for fighters. But “negotiating does not mean freeing terrorists,” he says. “Rather, it could facilitate the provision of justice for victims and punishment for terrorists.”

The truce

Last fall, as Burkina Faso’s general elections neared, all sides in the conflict seemed to have had enough. WhatsApp videos surfaced showing what looked like negotiations in Sollé, not far from Djibo, between local volunteer fighters and jihadis, according to local and international reports.

“We don’t know what groups these alleged jihadists were aligned with, but in the video, there was talk about peace,” Mr. Zombre says.

Mutually initiated talks also took place between local representatives of Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin, an Al Qaeda-backed group originally from Mali, and community leaders in Soum, according to Mr. Savadogo.

But the terms of most talks remain unclear. In Djibo, for example, some accounts from analysts and reporters say that it was local traditional leaders who negotiated for a cease-fire and free movement for civilians, while others assert that the jihadis themselves may have initiated the peace, seeking to recuperate after suffering major losses.

Whatever the case, the results were evident. Between November and January, there were almost five times fewer attacks in Djibo compared with the same period a year earlier, according to the New Humanitarian’s monthslong investigation. In areas controlled by extremists, travel restrictions were lifted, although women were still forced to wear a full veil, and men, trousers hemmed above their ankles in Islamic tradition.

But local leaders were confused, reporters and analysts say, with the central government failing to communicate a clear deradicalization and reintegration pathway for the returning fighters.

“The truce is over [and] we are heading in a bad direction,” says Andrew Lebovich, a researcher with the European Council of Foreign Relations. “It’s likely that what led to the truce was the jihadists needing a break to recuperate. There are still attacks in Djibo and incidents are ticking back up.”

In neighboring Mali, meanwhile, militant Islamic group Katiba Macina struck a deal in March with local farmers along the border with Mauritania, according to French radio station RFI. One month later, the cease-fire, though shaky, appears to be holding. Representatives from High Islamic Council of Mali – whose former leader, the influential religious figure Mahmoud Dicko, has pushed for negotiations – are currently working to extend the peace.

To talk, or not to talk?

Not everyone is on board with the talks, however. In Burkina Faso, some critics firmly oppose negotiations on principle – including Albert Ouedraogo, a former minister of education and professor at the University of Ouagadougou. “The government’s line is to refuse any dialogue with those who sow death – I stick to this posture,” he writes to the Monitor over a WhatsApp interview. “Who will compensate the victims and [punish those who] have sown terror?”

Others say dialogue could sow seeds of stability across the region. In January, Burkina Faso’s President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré appointed a national reconciliation minister to address ethnic divisions, which have exacerbated the insurgency. Across the border in Mali, the country’s transitional government has signaled openness to dialogue with insurgents.

Analyst Boubacar Ba, of the Bamako-based Analysis Centre on Governance and Security in the Sahel, harbors hope for such initiatives. He saw for himself how much the negotiated peace meant to Malian locals, even if no one was held to account for the violence perpetrated. “People were in tears,” he says. He recalls seeing nomadic herders (many of whom have been accused of having ties to jihadi groups) and sedentary farmers, who have traditionally been pitted against each other, “grouped together, holding hands and talking to each other.”

“Others hurriedly took their carts to reach their villages that had been abandoned for many months,” he adds. “All believe that this [agreement] is the beginning of a new era. They also recognize that the road to peace is long and difficult. It is a beginning and we must believe in it.”

In both countries, analysts emphasize, local groups are crucial in advancing dialogue. “The growing number of peace-building efforts shows that the crisis is producing new spaces of local governance outside the realm of state control and authority [and filling] the gaps left by state-led diplomatic efforts,” Niagalé Bagayoko, chair of the African Security Sector Network, a think tank, wrote in The Africa Report in February, after a G5 Sahel summit in Chad.

Questions remain, however. What would justice look like, once victims live side by side with their aggressors? Will larger groups like Al Qaeda continue to wield influence over local militants? And can national governments in the Sahel align their military tactics with this bottom-up approach?

Across the region, negotiations hold hope, Mr. Savadogo insists, if they are conducted with smaller, local insurgent factions rather than with hard-liners leading transnational networks. “There are local groups with whom we can negotiate because they are insurgents forced to take up arms to demand good governance,” he argues. “This will isolate the larger groups … and make it possible to win the fight.”

‘We need one another’: Communities of color unite against injustice

Blaming crimes or problems on racial groups can sow divisive distrust and fear. Some Asian and Black Americans are working together to protest hate crimes.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Noorulain Khawaja Correspondent

After the recent mass shootings in Atlanta, in which six women of Asian descent were killed, communities of color are mobilizing together to battle racism. “The fact that so many Blacks and Hispanics marched in solidarity with Asian groups … is a positive indication that minorities see injustice against one group as injustice against all,” says Earl Ofari Hutchinson, author of “Why Black Lives Do Matter.”

Yet he wonders whether that cross-activism will go beyond policing and anti-racism. “Will that unity translate into unity … on such issues as voter suppression, housing, jobs and education, and health disparities?” he asks.

Some young activists believe it will. Emma Tang, a Taiwanese American student at New York University, calls this moment the “birth of a fresh, new, powerful coalition.”

Since being attacked in what her friends call a hate crime, she appreciates the support of other racial groups more than ever. At a recent protest, she witnessed a diverse crowd fighting for Asian women. “It … makes me feel safe knowing that there are people looking out for us,” she says.

“Stop Asian Hate would not be around today without Black Lives Matter,” she adds. “We need one another to advance our liberation.”

‘We need one another’: Communities of color unite against injustice

Emma Tang, a Taiwanese American student at New York University, was sitting outside a Chinese restaurant last October, eating with her friends, when a white man approached her from behind and hit her over the head with a dirty bed sheet.

Shocked – and despite her friends saying they thought she was a victim of a hate crime – Ms. Tang never reported the incident to police. Instead, she took to Instagram, and her 84,000 followers.

But her posts didn’t go over well online. Black activists took issue with Ms. Tang for perpetuating stereotypes that Black people are dangerous and that Asian people need help. “I was trying to have a conversation about how Black people can stand in solidarity with Asian people more, and it came off badly,” says Ms. Tang. “Black activists started calling me out and they started having conversations with me.”

One of them was Kiara Williams, from Queens. “She was trying to address what the Asian community was going through and rightfully so,” Ms. Williams says, “but she was kind of villainizing the Black community.”

After the two spoke online, Ms. Williams invited Ms. Tang over for lunch, where the women bonded over their shared pain. “Both of our communities are there for each other. There is no, ‘You hurt me more. No, you hurt me more,’” says Ms. Williams.

The two are now friends and work together as “comrades” to advance Black and Asian solidarity. “I think we’ve both changed each other’s perceptions of our communities,” says Ms. Tang.

In the wake of the recent mass shootings in Atlanta, in which eight people were killed, including six women of Asian descent, communities of color are mobilizing together because of their shared struggles and common goal of battling racism. “The fact that so many Blacks and Hispanics marched in solidarity with Asian groups … is a positive indication that minorities see injustice against one group as injustice against all,” says Earl Ofari Hutchinson, a radio show host, political analyst, and author of “Why Black Lives Do Matter.” “This could be a huge political game changer in the future,” he adds.

Gabriel “Jack” Chin, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, also calls this moment a turning point. “There’s more discussion, there’s more anxiety, there’s more fear, there’s more identification of a particular problem than I’ve ever seen before. And the only thing I can analogize it to historically is the civil rights movement of the ’60s.”

An intersectional effort

Martin Luther King Jr. used the media to advance his civil rights cause, but the news coverage often failed to capture the racial unity at his demonstrations. “There were white people there. There were Latino people there. But it wasn’t necessarily covered that way,” says Clara Rodriguez, professor of sociology at Fordham University’s College at Lincoln Center. “It’s both history and this tendency to view groups separate from one another, and I think it contributes to people thinking in terms of ‘Well it’s that group, and I have nothing to do with that group.’”

For Ms. Tang, the fight is intersectional, but she acknowledges that there is anti-Black racism in the Asian American community, which can lead to distrust between the two groups. In fact, however, the notion that there are high levels of Black-on-Asian crime is false. Researchers at the University of Michigan found that, in 2020, 90% of perpetrators in reported anti-Asian incidents were white, and only 5% of perpetrators were Black.

While some may try to weaponize Black-Asian conflict, hate-inspired tragedies like the 2019 mass shooting targeting Mexicans at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas; police killings of Blacks and Latinos; and the Atlanta shootings are actually fueling unity. “What you have seen as a result of these highly visible and highly tragic events is the intensifying of a reckoning with how racism and discrimination have infected many of our systems and people at the same time,” says Clarissa Martínez-de-Castro, deputy vice president for policy and advocacy at UnidosUS, the nation’s largest Latino civil rights and advocacy group. “And they need to stand up and not only call it out, but do the work to address the disparate treatment and fight for equity.”

Some people of color, like Ms. Tang and Ms. Williams, are fighting for the collective – “to do right by all communities of color,” as Ms. Williams puts it. They are uniting to dismantle stereotypes like the “model minority” myth, which pits minority groups against each other. Asian Americans, for example, are often praised for being well educated and successful. And while it is true that they have the highest median income across racial groups, including white Americans, the income gap among Asian Americans is the largest within any racial or ethnic group in the country, with almost 10% of the community living below the poverty line. Rather than presenting an accurate picture of the diversity among Asian Americans, the “model minority” stereotype is held up to other groups as a sign of their failure.

What’s needed, says Dr. Rodriguez from Fordham, is to “get people to think in terms beyond race … to think in terms of what are the things that we have in common and how can we all benefit?”

Ms. Williams benefited from that unity when she attended her first protest after George Floyd’s murder. She was overwhelmed, she says, to see the multiracial makeup of the Black Lives Matter marches last summer. “For a long time, I thought Black people were alone.”

In fact, nonwhites across races share concerns on a variety of issues, including immigration reform and U.S. policy at the Mexico border. “I think Asians can understand some aspects of the Latinx situation as fellow immigrants. And, of course, there’s a lot of undocumented Asian people in the United States,” says Professor Chin from UC Davis. “Asian-Americans have an experience of being hassled by the police in the same way as Latinx people at the border.”

Cross-activism on matters like policing and anti-racism is unprecedented right now, but according to Mr. Hutchinson, the radio show host, it’s still not enough to create true solidarity. “Will that unity translate into unity in a fight together on such issues as voter suppression, housing, jobs and education, and health disparities?” he asks.

Mr. Chin wonders as well, noting that, despite the current unity, there is not “a utopian agreement among all these racial groups.”

“We need one another”

Yet some young activists believe this moment is the beginning of their revolution. Ms. Tang calls it “the birth of a fresh, new, powerful coalition of BIPOC communities aligning together in the grassroots sphere” (referring to Black, Indigenous, and other people of color).

To continue developing strong, sustainable coalitions, Mr. Hutchinson says, protesters need “planning, proper issues-framing, consistency, and most importantly, aware, politically engaged, proactive leadership.”

Ms. Williams, for one, says she is dedicated to supporting other communities of color because she sees their struggles against oppression intertwined with hers. “It’s about being mentally strong, never backing down,” she explains.

Ms. Tang concurs. At a recent solidarity march, she witnessed a diverse crowd of Black transgender women, Indigenous people, and Latinos fighting for women of Asian descent. “It feels very validating, and it makes me feel safe knowing that there are people looking out for us. And we don’t have to fight this on our own,” she says.

Ms. Tang, who hides a taser up her sleeve whenever she leaves her apartment, says she’s less fearful now whenever someone yells a racial slur or harasses her in the streets. “Stop Asian Hate would not be around today without Black Lives Matter,” she says. “Our movements have always bounced off of each other and been inspired by each other. Historically we need one another to advance our liberation.”

For ‘Limbo’ filmmaker, the refugee story is a universal one

“Limbo” is a movie about a Syrian refugee on a remote Scottish island that’s battered by a near-constant gale. (The last time wind played such a major role in a movie was “Twister.”) I interviewed the director about how this story of identity loss is relevant to all of us.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

On Friday, a new addition to films depicting refugees, “Limbo,” opens in theaters. Writer-director Ben Sharrock’s movie features a young Syrian, Omar (Amir El-Masry), who lives in Scotland with other refugees while they wait years for their asylum claims to be processed. The character’s journey is one of rediscovering his true self.

Mr. Sharrock, who is Scottish and briefly lived in Damascus just prior to Syria’s civil war, researched the movie by collaborating with organizations Refuweegee and Re-Act: Refugee Action Scotland. He explains in an interview that he set out to do something unconventional by Hollywood standards – putting the refugees front and center – but also to address a universal theme.

“Everyone changes their identity across the course of their lives in one way or another, just even from losing a job or retiring,” he says. “There’s a universality in Omar’s journey to coming to terms with his circumstances and with his identity, and then also with his ambitions and his hopes for the future.”

For ‘Limbo’ filmmaker, the refugee story is a universal one

When Ben Sharrock wrote a movie about the experiences of refugees, he wanted to change the usual Hollywood script. “Limbo,” opening in theaters on April 30, is certainly unconventional. For starters, its serious subject matter often has a comedic tone. And it’s set on a fictitious remote Scottish island populated by more sheep than people.

Mr. Sharrock’s latest film is about a young Syrian, Omar (Amir El-Masry), who lives in austere housing with other refugees while they wait years for their asylum claims to be processed. Omar’s alienation is enhanced by the island’s treeless landscape, scoured by a near-constant gale. The Scottish locals maintain a wary distance. Omar’s journey is one of rediscovering his true self.

The Scottish director – who briefly lived in Damascus just prior to Syria’s civil war – researched his movie by collaborating with organizations Refuweegee and Re-Act: Refugee Action Scotland. In an interview, he discusses the making of “Limbo.”

Q: Why is this story about refugee experiences so important to you?

It reached back to my time living in Syria and reflecting on the relationships – the friendships that I made there, and then seeing people that I met who’ve since become refugees, and also others that I’ve lost touch with. The representation of refugees in the media really stood out to me. That’s also connected to my undergraduate degree in Arabic and politics. You’re studying the construction of “the other” ... and I then went into studying the representation of Arabs and Muslims in American cinema and TV.

Q: When it comes to building bridges across cultural divides, can you speak about the power of story and cinema?

A lot of films use this approach where they use a Western character as a vehicle to tell a story about the other. We often get this sort of cultural reconciliation narrative where we have these two cultures clashing and then, by the end, everyone’s best friends and really understanding of each other. It feels like a cinema trope. I was really interested in interrogating that as an idea and putting the refugee characters front and center. Cinema in general has always been a very powerful tool to create change and to cause people to think differently.

Q: How did you endeavor to help audiences see themselves in these characters?

I wanted to make a film about the refugee crisis, without making a film about the refugee crisis. Omar is struggling with this grief for the loss of his identity – or what he regards as the loss of his identity. It’s about his relationship with his family back home and the relationships that he forms on the island itself. The themes that are explored around identity are universally relatable. We all, at some point, will go through some sort of identity crisis. Everyone changes their identity across the course of their lives in one way or another, just even from losing a job or retiring. There’s a universality in Omar’s journey to coming to terms with his circumstances and with his identity, and then also with his ambitions and his hopes for the future.

We were very deliberate in terms of how he was [filmed], as well as having the characters looking just beyond the lens. It creates a different connection with the audience in the cinema because we’re not shooting the characters from a three-quarter angle. The characters are almost looking directly at us all the time. It’s almost like those conversations are being had directly between us and the characters on screen.

Q: When you were writing the story, you became particularly close to one Iraqi Kurdish asylum-seeker. How did his story influence the film?

He was waiting for his asylum claim to come through for six years. He actually became homeless for a period of time. Speaking to him, what was really central to his journey and experience was losing his sense of identity.

He has a great sense of humor and he loves to laugh. And, like many of the people that I spoke to along the way, they really liked the idea of using humor in the film and for the film not to be this kind of forlorn human drama that we’re used to seeing.

Q: Have you had any responses to the movie that stood out to you?

In a Zurich film festival, at the Q&A afterwards, someone stood up and he was in tears. He said, “Thank you so much for making this film. This is my life. This is my experience. I arrived here 20 years ago. I lived this.” He could barely talk through the emotion. The whole cinema just went silent. Everyone was fighting back the tears in that moment. There’s just been really positive feedback.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Biden taps into a new ‘discovering’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In his first speech to Congress, President Joe Biden spoke of America “dreaming again, discovering again.” That shift is the basis of his proposals for a post-pandemic national renewal, starting with climate technologies. “Folks, there’s no reason American workers can’t lead the world in the production of electric vehicles and batteries,” he cited as one example.

As more people come out of the pandemic shell of isolation and anxiety, will they be more curious, more inventive? Certainly, companies are rethinking the dynamics of work and the workplace. Schools have been forced to design new ways of learning. “Now, more than ever, curiosity matters,” writes F.H. Buckley, a George Mason University professor in a new book, “Curiosity: And Its Twelve Rules for Life.”

As the U.S. Patent Office notes, its award system is designed to find success stories that “will inspire others to harness innovation for human progress.” The uses of adversity may be sweet, as Shakespeare said. But adversity can also liberate thought to see infinite possibilities.

Biden taps into a new ‘discovering’

In early April, the federal agency that was invented to reward inventiveness, the U.S. Patent Office, reinvented one of its incentives for new discoveries. It changed its awards program, known as Patents for Humanity, to solicit new inventions related to COVID-19. The pandemic had sparked a call for curiosity-driven breakthroughs.

This is what President Joe Biden might have meant Wednesday in his first speech to Congress, when he said America is “dreaming again, discovering again.” That shift is the basis of his proposals for a post-pandemic national renewal, starting with climate technologies. “Folks, there’s no reason American workers can’t lead the world in the production of electric vehicles and batteries,” he cited as one example. “We have the brightest, best-trained people in the world.”

As more people come out of the pandemic shell of isolation and anxiety, will they be more curious, more inventive? Certainly, companies are rethinking the dynamics of work and the workplace. Schools have been forced to design new ways of learning. For the economy, the need has never been greater for inventions that will create wholly new types of jobs. Last year, the global workforce lost the equivalent of 255 million full-time jobs.

“Now, more than ever, curiosity matters,” writes F.H. Buckley, a George Mason University professor in a new book, “Curiosity: And Its Twelve Rules for Life.” “In 2020, we learned just how much our health, our happiness, our sanity, depends upon it. ... There is only one way out of the madness, and that is to let our curiosity take us by the hand and lead us.”

He cites periods of history when “we seem to make a leap and shake off the fetters that bind us.” The key to curiosity, he writes, is to take an interest in other people, a form of love. Curiosity not only leads to new discoveries. It is also a cure for fear.

“Follow your curiosity, therefore,” he writes. “It will encourage you to take risks, to be creative, sociable, and entertaining. It will ask you to think about how you should live.”

Also in April, Congress held hearings on the future of American innovation. One expert, Farnam Jahanian, president of Carnegie Mellon University, said the pandemic has shined a light on the “ecosystem” of science and innovation. Now, he said, the nation must mobilize to meet new challenges “while renewing and reinvigorating the promise of discovery and innovation to expand economic and social mobility.”

A big focus in the hearings was Mr. Biden’s plan to spend $50 billion for research in new technologies as a source of jobs. “Curiosity-driven research has proven to be an engine of economic growth,” said Sethuraman Panchanathan, director of the National Science Foundation.

Curiosity, however, should not be for only material gain. As the U.S. Patent Office notes, its award system is designed to find success stories that “will inspire others to harness innovation for human progress.” The uses of adversity may be sweet, as Shakespeare said. But adversity can also liberate thought to see infinite possibilities.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The spring within

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Dilshad Khambatta Eames

Sometimes circumstances may seem bleak. But the ever-active light of Christ is here to inspire, rejuvenate, and heal.

The spring within

In temperate latitudes, as the light begins to shift and the days become a little longer, a hint of color appears on the tops of bare trees, and icy streams begin to thaw out, one can feel the joy of renewal in the coming of spring. One senses a breakthrough! Hope and expectancy fill the air as the landscape transforms into one of activity and color.

But there is, in fact, activity filling those long months of winter. For instance, we cannot see the strengthening of the root systems of trees. Yet all the natural developments of ecology are taking place.

At times in our own lives, we may feel overwhelmed by the gray days of “winter,” so to speak. Perhaps the end of a relationship, financial worries, or a health situation causes discouragement. I’ve experienced this before, even all at once! But I have to say, prayer throughout those experiences has helped me realize, more than ever, that there is a powerful divine order – the power of God, divine Life, sustaining us. This divine “order,” or spiritual law, is explained in Christian Science, which shows that the universe is the eternal and infinite expression of the one God that is pure Love and light.

If we open our hearts to this activity of divine light within us and trust its guiding, healing power – just as we trust the coming of spring – then we begin to recognize our resilience and self-worth as God’s own reflection. No challenge, however severe, can separate us from God’s infinite goodness, and absolutely no one can be left out of it. This understanding enables us to recognize the Godlike qualities within everyone – the Christliness and goodness that you and I actually consist of.

It’s been helpful for me to realize that “wintry” or “wilderness” times can also be times of spiritual progress that bring healing, even if it doesn’t always feel like it. The prophet Isaiah spoke of a voice that said, “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord” (Isaiah 40:3, New Revised Standard Version).

Years ago, a relationship I’d been in for a long time suddenly ended. I felt sad, hurt, afraid, and lost. I was living in a new city on a student budget, and also facing a lingering problem with my health. Everything seemed pretty dark and dismal.

But a persistent intuition kept me from giving in to feeling sorry for myself. I’ve since come to realize that this voice of hope was the Christ, God’s message of love and care for all. Through Christ, I felt connected to divine Love and inspired to “wait on God,” a phrase Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, uses in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 323). For me, this “waiting on God” was a heartfelt desire to feel God’s goodness.

For a while, there seemed to be no visible progress. Yet I knew that my communion with God was strengthening me, helping me let go of pride and fear, and nurturing my spiritual growth.

And then I noticed signs of progress. My health normalized. The regeneration wasn’t just physical, but mental, too. I began to feel God’s love for me, and mine for God. Cold, fearful thoughts softened into kinder, repentant ones. I became more patient, humble, and loving. I was filled with gratitude for what felt like the returning of spring within me, and perceived “the beauty of holiness” (I Chronicles 16:29), or light of Love, shining through everyone. These blessings radiated outward, improving my interactions with those around me.

In an article titled “Voices of Spring,” Mrs. Eddy writes about these blessings of transformation. “It is good to talk with our past hours, and learn what report they bear, and how they might have reported more spiritual growth. With each returning year, higher joys, holier aims, a purer peace and diviner energy, should freshen the fragrance of being” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 330).

If you are struggling to overcome difficulties of any sort, don’t be afraid to “wait on God.” As you faithfully cherish your Christly nature and the light of God, don’t be surprised when you begin to feel a more consistent and spiritual satisfaction, renewal, and a purer peace – as Christ Jesus put it, the kingdom of God within you (see Luke 17:21).

A message of love

Welcome home

A look ahead

You’ve reached the end of today’s package of articles. We’ll be back with more tomorrow, including a different kind of travel story. A former dairy farmer shares how country walks in Switzerland during the pandemic taught her to live in the here and now.