- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The ethics of swinging for the fences

In today’s edition, we have a path to democracy (Sudan), leadership without leaders (Hong Kong), Democrats for Trump (Kentucky), next-gen farmers (Alaska), and empathy through music (Iraq via Chicago).

But first, let’s talk baseball. If Shakespeare were alive, he might declare that “something is rotten” in the state of the ballpark.

We are at the All-Star break of Major League Baseball (MLB). Pete Alonso won the Home Run Derby Monday night. But instead of enjoying this annual apogee of summer, fans are abuzz about juiced balls.

Home runs are up a whopping 19% over last year. Players are on pace to hit 6,668 home runs, smashing the record 6,105 hit in 2017.

And dingers are going farther than ever, Sports Illustrated reports.

Last month, MLB confirmed the balls are, well, different. The drag coefficient is lower. Less drag means longer flights. The drag is lower because the “pill” (the core) is consistently centered, said the MLB commissioner. But he insists no changes were made in the baseball production process or the materials.

Baseball has long been a mirror of American societal values, a kind of moral compass. The sport champions individual achievement as well as team cohesion. It’s built on adherence to rules and sportsmanship. (Remember the Pete Rose lifetime ban?) It has charted the evolution of U.S. civil rights (see Jackie Robinson).

To some, the 2019 home-run binge smells like someone is messing with the integrity of the national pastime. “It’s a ... joke,” complains Justin Verlander, the starting pitcher in Tuesday night’s All-Star game.

But hitters aren’t complaining. And fans seem conflicted, torn between tradition, precedent, and the fireworks of more offense.

If Yogi Berra were here, he’d have an appropriately ambiguous response: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Sudan reaches a power-sharing deal, but will it stick?

What happens after a longtime dictator is ousted? Sudan shows that the path to progress is seldom straight. A surprise deal to democratize the country is being met with guarded optimism.

Things hardly looked promising for the protesters in Sudan demanding civilian rule. The country’s Transitional Military Council had publicly cut off negotiations with the opposition and shut down the internet. And security forces loyal to the ousted president, Omar al-Bashir, attacked and burned the main protest encampment, killing more than 120 people.

But the violence backfired – and sparked serious diplomatic efforts to resolve the crisis. Washington played a lead role, and so did the African Union and Ethiopia. The result? An unexpected deal due to be signed this week that sets up a military-civilian council for a little more than three years – led first by a soldier, then by a civilian – that will oversee the creation of a civilian government.

Opposition leaders have hailed the agreement as a victory, but there are doubters. “We would like to see many more guarantees” from the military, said one pro-democracy demonstrator in the capital, Khartoum, according to Al Jazeera. “Because they’ve made many promises on handing over power, only to backtrack later on.”

Sudan reaches a power-sharing deal, but will it stick?

Little more than a month ago, the Sudanese protesters who had brought down military dictator Omar al-Bashir in April had every reason to believe their popular bid to end military rule had failed.

General Bashir had been replaced by new military leaders no more sympathetic to democracy, and on the night of June 3, shadowy security forces loyal to the ousted president attacked and burned the main protest encampment, killing more than 120 people.

Activists were forced into hiding as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – the rebranded janjaweed militia accused of conducting genocide in western Darfur – prowled the streets of the capital, Khartoum. Corpses of victims were pulled from the Nile River.

But that brutal crackdown now appears to have backfired. Last week, the military and the civilian opposition announced a surprise deal to democratize Sudan that was due to be signed this week.

Rather than crushing the monthslong campaign for civilian rule in one of Africa’s largest and most strategic nations, the violence on June 3 triggered a determined international effort to resolve the crisis.

African Union and Ethiopian mediators stepped in, the United States appointed a special envoy, and Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates muted their backing for the Transitional Military Council (TMC), which had taken over from General Bashir.

The agreement represents a rare sign during the Trump administration of how the U.S. can still exert diplomatic pressure to ease a regional crisis when it chooses to.

Under the deal, Sudan will return to full civilian rule in a little over three years. “Today our revolution has won and our victory shines,” the Sudanese Professionals Association, a key element of the opposition alliance, said in a statement.

Still doubts

But doubts persist whether the generals, who have ruled Sudan for three decades, will actually relinquish power.

“There are a few quite obvious concerns,” says Alan Boswell, a Sudan analyst for the International Crisis Group (ICG), a Brussels-based think tank. “One is that if it took all of this coordination to hit the right pressure point on the military council, that’s an extremely difficult thing to sustain for 21 months.”

That is the period during which a soldier will be president of a new 11-member sovereign council, made up equally of civilian and military members, with the final seat given to a civilian approved by the military. By early 2021, TMC head Gen. Abdel-Fattah Burhan announced on Sunday, the military will return to barracks and hand over to a civilian council leader.

“This basically provides a period of time for the military council to regroup, try to consolidate power, try to divide the opposition, and try to wriggle its way out of actually handing over power,” cautions Mr. Boswell, contacted in Nairobi, Kenya.

The new council is to oversee the formation of a transitional civilian administration that will govern for three years and prepare elections – a key demand of protesters.

Opposition leader Omar al-Digair said he hoped the deal would herald “a new era” because it “opens the way for the formation of the institutions of the transitional authority.” But while crowds celebrated news of the unexpected deal, many protesters expressed mistrust of the military.

The opposition plans another mass protest on July 13 and a campaign of civil disobedience thereafter.

“The real leadership is the street,” protester Kobays al-Kobany told Britain’s Channel 4 TV. If the new council does not meet popular expectations, he said, “then our tools of protest are still in place. We are ready to activate, escalate, and start over. At the end of the day, our government will be a civilian one, no matter what.”

“The outline of the deal as it was presented on Friday made me very skeptical,” says one Sudan analyst in Europe who asked not to be named.

“It keeps [General] Burhan as de facto head of state for a long time,” he says. “The broader public has no more patience with the TMC. So there is a risk that the [opposition leadership] will lose credibility and that the revolution will radicalize.”

“The question is: Will international actors find a way to keep the pressure up and make sure the military council abides by what it promises?” asks Mr. Boswell, the ICG analyst. “And will the Sudanese opposition stay united enough to hold their feet to the fire?”

A sharp turnaround

The deal was a sharp turnaround for the TMC, which had publicly cut off negotiations with the opposition and, after June 3, had shut down the internet. Behind those moves, many observers believed, were Saudi Arabia and the UAE, undemocratic hereditary monarchies that promised $3 billion to bankroll continued military rule.

Sudan and the RSF have deployed forces to Yemen for years, fighting as part of a Saudi and Emirati-led coalition against Iran-aligned Houthi rebels.

But after the protest camp was violently dispersed on June 3, the African Union suspended Sudan, and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed flew to Khartoum to mediate. And the U.S. – which appointed veteran diplomat Donald Booth as special envoy – stepped up efforts to pressure its allies Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

“The main point was, everyone’s interests might not totally align, but there didn’t seem to be a clear constituency for Sudan falling apart,” says Mr. Boswell. Washington “needed to really lead in pressuring Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to change their direction,” he adds. “They’ve started at least saying the right things.”

“We received a direct message from the White House: Facilitate a deal between the military and the protesters,” one Egyptian negotiator told The Associated Press. The same message had been delivered to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, he said, paving the way for compromise.

A Sudanese military official told the AP that the junta got the same message.

“The Americans demanded a deal as soon as possible,” he said. “Their message was clear: power-sharing in return for guarantees that nobody from the [TMC] will be tried.”

Then came a secret meeting in Khartoum on June 29, at which U.S., British, Saudi, and UAE diplomats convinced Sudanese military and opposition leaders, all in the same room, to accept the African Union and Ethiopian proposals.

“It was really a tag-team effort from everyone. ... This was America-Europe among many other powers, rather than the old days of just America in the lead,” says Mr. Boswell. “There were a lot of moving parts.”

Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the deputy head of the TMC and commander of the RSF, announced that the deal would be “inclusive” and satisfy the “ambitions of the Sudanese people and its pure revolution.”

But not all celebrating on Sudan’s streets were convinced. Among them was Mohamed Ismail, an engineer quoted by Al Jazeera.

“We would like to see many more guarantees from the TMC,” he explained. “Because they’ve made many promises on handing over power, only to backtrack later on.”

Hong Kong protests: Is anyone in charge?

What does leadership without leaders look like? For now, Hong Kong’s young protesters are doing without chiefs. But the stakes are high, both for individuals and for the pro-democracy movement.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Suzanne Sataline Contributor

As Hong Kong’s protesters keep taking to the streets, observers have remarked that their movement is nimble, messy – and leaderless.

But there are diffuse pockets of quiet influence (and sometimes not so quiet), with a handful of young people sometimes stepping to the forefront. The pro-democracy campaign’s fluidity has helped to limit arrests and public censure, and the big-tent approach allows for greater input. Sometimes, though, it means rule by the masses – creating challenges for both day-to-day activities and the movement’s future.

Even participants can be bewildered as to what’s happening as it’s happening. And after an intense month of multiple meetings, rallies, or marches each week, many protesters say they are tired and unsure of the direction.

With consensus decisions, “it’s hard to strategize and innovate,” says David S. Meyer, a professor at the University of California, Irvine and an expert on social movements. “Usually the easiest thing to agree on is what they’ve already been doing. You always have the risk that a breakaway coalition opts out and does what it wants to do. When there’s nobody in charge with continuing on after the peak enthusiasm has passed, it falls apart.”

Hong Kong protests: Is anyone in charge?

On July 1, the 22nd anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from Britain to China, hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers filled city streets demanding, yet again, that the government grant them democracy and withdraw an extradition bill. A smaller group of young people, meanwhile, had a different plan: to impede the government’s flag-raising ceremony that would commemorate the day.

Police batons and pepper spray swiftly ended that idea. Standing by the city’s legislative complex, a dozen or so people assembled a crowd of a few hundred to discuss their next move. Replace the Chinese flag at the exposition center with a new protest emblem? Most people didn’t see the point, since the ceremony had ended. March to the residence of the territory’s chief executive, Carrie Lam? Police could easily surround protesters on the narrow road. The third choice was even riskier: Break into the city’s sleek glass and steel government center. The complex had been the site of legislators’ debates over the controversial bill to allow extraditions to China, until Mrs. Lam shelved the bill in mid-June in the face of public uproar – but did not formally withdraw it.

After almost an hour of debate, the crowd voted. About three-quarters chose Option 3.

For hours, young people rammed metal carts and street signposts into the tempered glass doors and windows of the territory’s lawmaking chamber as police stood by and then retreated. Once inside, the protesters covered walls with political slogans. They blacked out the faces on official portraits, smashed the members’ electronic voting system, and spray-painted over the city emblem. One protester, decked in the day’s unofficial uniform of a yellow construction helmet, black clothes, and face mask, dramatically ripped apart a copy of the city’s constitution.

When it appeared that many protesters intended to leave, one young man jumped atop a lawmaker’s desk. With TV cameras recording, Brian Kai-ping Leung, a graduate student in the United States, removed his mask, risking future prosecution.

“I took off my mask because I want to let everyone know that we Hong Kongers have nothing more to lose,” he said. If they left, he warned, “Hong Kong’s civil society will go backwards 10 years, and we will never be back here.”

For those few hours, Hong Kong’s tenacious tribe of demonstrators had a chief.

Observers have remarked for weeks that this protest movement – which has expanded its mission from axing the extradition legislation to demanding direct elections for chief executive – is a leaderless movement, creative, nimble, messy, and shrewd. Participants use online forums and encrypted Telegram channels to propose actions, swap tactics, and vote on strategies. They have been unafraid to confront the police, but will sometimes do so and then suddenly retreat.

Participants had learned from the 2014 democracy campaign, nicknamed the Umbrella Movement, that sitting on roads and confronting the police night after night produced little more than injured people and public bitterness. Instead, the new movement has taken inspiration from the words of hometown son and martial artist Bruce Lee, as one video declares:

We are formless.

We are shapeless.

We can flow.

We can crash.

We are like water.

While the democracy campaign does not have official leaders, it is not leaderless. There are diffuse pockets of quiet influence that sometimes make their presence known loudly. For now, that organic nature and fluidity have limited the number of arrests and public censure. The big-tent approach has allowed for greater input.

But sometimes it means rule by the masses. That creates challenges for day-to-day operations and, perhaps, the movement’s future.

“Hong Kong might be construed as a leaderless movement, ... and yet there is leadership and coordination,” says Paul Chang, a professor of sociology at Harvard University who studies social movements. “It’s a leaderless movement where people still take the lead.”

Day-to-day scramble

Several key actions have been suggested or organized by some young people active in an ardent campaign to foster pride in Hong Kong’s history, language, and culture. The belief in Hong Kong’s separate identity and sovereignty has intensified as concerns mount that Beijing is eroding the “one country, two systems” arrangement, which was supposed to keep Hong Kong relatively autonomous until 2047.

Many of the actions, though, are decided on the fly. After an intense month of multiple meetings, rallies, or marches each week, many protesters say they are tired and unsure of the direction.

When you’re “making consensus decisions, it’s hard to strategize and innovate,” says David S. Meyer, a sociologist at the University of California, Irvine and an expert on social movements. “Usually the easiest thing to agree on is what they’ve already been doing. You always have the risk that a breakaway coalition opts out and does what it wants to do. When there’s nobody in charge with continuing on after the peak enthusiasm has passed, it falls apart.”

On most protest days, a loyal army of volunteers tackles the unglamorous work of setting up first-aid stations and resource tents stocked with water, goggles, and masks. Even those arrangements can be last-minute and ad hoc.

“The protesting stuff happens with limited time for announcements, for coordination. The best we can do is to coordinate the colleagues in our own hospital and try to get material down there and nursing stations down there,” says nurse Jason Siu, a frequent volunteer at protests. “There are times when we’re overwhelmed, when police try to clear the road and fire tear gas.”

Several times, patient lawmakers have intervened between protesters and police. Twice when strikers surrounded the police headquarters in June, several lawmakers convinced members of the crowd to calm themselves, and not invade. Yet protesters have declined help from more experienced activists. On June 26, when legislator Eddie Chu and student activist Joshua Wong called a group vote to decide if a siege on the police building should end, the crowd refused to take part. Similarly, on July 1, protesters pulled away lawmakers who tried to stop people from breaking the legislature’s windows.

Edmund Cheng, an assistant professor of governance at Hong Kong Baptist University, says he’s not sure if the people who voted on the break-in at the legislature were the same people who vandalized the building. “A small number of people can in a way jeopardize the entire movement,’’ he says. “Nobody can call someone off. It is not that easy.”

Even participants can be bewildered as to what’s happening as it’s happening. As tensions mounted one night at the police headquarters, Tobey, an undergraduate who declined to give his last name, reluctantly left to catch a bus home. “I’m confused,” he said. “We’re not sure we can achieve anything. The things we have achieved were by accident.”

On the front line

Though the protests remain diffuse, without a visible leader, a few young activists have stepped to the forefront of some actions. Thousands of young people besieged the police headquarters for a second night in June after young activists Baggio Leung, Tony Chung, and Joe Yeung urged them to do so. All three have been active for years in a small campaign demanding Hong Kong’s independence from China. (Mr. Leung was elected to the legislature in 2016, but was disqualified for insulting China during his oath of office.) With police barricaded inside by the protesters’ blockades, Mr. Yeung sat atop a street sign and led the crowd in loud chants. He was later arrested.

Another person playing a leadership role has been Ventus Lau, a young politician who once backed Hong Kong independence and was then barred from seeking a legislative seat. He organized a one-day demonstration marathon outside international consulates on June 26, urging leaders at the Group of 20 conference in Japan to support their demands. On Sunday, he arranged a peaceful march in a bustling shopping area. Tourists from mainland China snapped photos, and some accepted leaflets, as they watched a mass social effort that would be prohibited where they live.

“I’m a bit worried if too many people recognize me as the organizer of a rally,” he says. “I think I worry that some people will think that I want to make myself more popular or my name big. I’m rather worried I will get some criticism. I’m not worried about my safety or responsibility.”

Mr. Lau emphasized that he had a great deal of help. “You can say I’m one of the organizers, but I can’t know everything,” he says. “People are doing their thing and throwing it out to the Telegram group – ‘I’ve done this.’ ... I’m inside the circle, and [even] I can’t have a full picture.”

Operations can be “very confusing, very very confusing,” says Bud Lau, an insurance agent in his 20s. (He is a friend, but not a relation, to Ventus Lau.) To pull off Sunday’s march – which organizers said drew more than 200,000 people, and police pegged at 56,000 – he continuously chatted through Telegram with about 20 administrative volunteers who ran their own volunteer groups on the app. That included channels for transport, resources, promotions, first aid, and marshals.

His job that day was to be the emcee, but things went awry, including a spam attack on one of the Telegram groups.

“Every one of us is a volunteer,” Bud Lau says. “If there is no physical group or teams we cannot make things very organized, and we cannot give orders.”

His friend Ventus Lau says he will happily join next week’s rallies, now in the planning stages, as a participant, not a leader. “Until some day when we don’t have a direction, and I will try to make up a new idea.”

Why these Kentucky Democrats still love President Trump

In the polarized U.S. electorate, eastern Kentucky stands out as a deep-rooted Democratic region where President Donald Trump is very popular. We wanted to see what’s behind this shift in identity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

In seven counties of eastern Kentucky, Democratic voters vastly outnumber Republicans – by as much as 6 to 1. But in 2016 candidate Donald Trump swept the area by large margins. In 2020 it’s quite likely he’ll do so again.

That’s because east Kentucky Democrats are perhaps Democrats from another era. Their partisanship is part of their geographic identity, handed down from mother to son. Most Southern Democrats flipped to the GOP during the civil rights era – but not this region. That’s because it was heavily white to begin with, and civil rights just wasn’t a big issue, say political scientists.

Now this coal-rich region is experiencing change similar to the rest of the region. True, many voters still pull the lever for Democratic local officials. They’ve opposed the state’s Republican senior senator, Mitch McConnell, the last two times he’s run. But many voters here love President Donald Trump.

Mr. Trump’s vocally pro-coal. He’s against abortion and for gun rights. And in an area that pulses with religious feeling, many say Mr. Trump is the pro-Christian choice, whatever his personal behavior. They don’t see any 2020 Democrat who might win them back.

“The Democratic Party leadership in Washington has left – just completely left – people like us,” says Earl Kinner Jr., owner and editor of Morgan County’s Licking Valley Courier. “We’re no longer a priority.”

Why these Kentucky Democrats still love President Trump

Earl Kinner Jr. chuckles, imagining what his father would say.

His father, Earl Kinner Sr., bought the Licking Valley Courier in the mid-1940s to cover local news in West Liberty, a town of fewer than 4,000 on the banks of the Licking River. Mr. Kinner Sr. was clear that his paper would lean left. No one was surprised. West Liberty had been a Democratic town for as long as anyone could remember.

In some important ways it still is. Like land, accents, and professions, political identity is passed down through generations here. Eastern Kentuckians like Mr. Kinner Jr. call themselves Democrats to this day because their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers were Democrats: the party of the workingman.

But in recent years this tradition has confronted a new political reality. As the economy got worse for Kentucky Democrats (as they call themselves) over the last two decades, it seems like Washington Democrats (as they call them) just got louder about guns and abortion – two issues that already put Kentucky Democrats on the fringe of the party.

So prior to the 2016 presidential election, Mr. Kinner, who took over the Courier from his father more than three decades ago, found himself writing opinion pieces from his one-room newsroom in support of a New York real estate tycoon running as a Republican.

The tycoon promised to bring back the coal industry, eastern Kentucky’s economic mainstay. He was on the region’s side of social issues like abortion and seemed to talk their language of Christian faith.

Eastern Kentucky Democrats like Mr. Kinner say that in 2016 they finally found a conservative Democrat they could support: Donald Trump. Candidate Trump swept the region. Voters here say that so far, there’s no 2020 Democratic candidate that can win them back.

“The Democratic Party leadership in Washington has left – just completely left – people like us,” says Mr. Kinner. “We’re no longer a priority.”

Trump Democrats

To a Democratic Party staffer flipping through statistics at a desk in Washington, there is a core area of rural eastern Kentucky that appears as if it might be fruitful territory in the 2020 presidential election.

In the seven counties that make up this area – Morgan, home to Mr. Kinner’s Licking Valley Courier; Nicholas, Bath, Menifee, Rowan, Elliott, and Wolfe – Democratic registered voters vastly outnumber Republican ones, sometimes by margins of 6 to 1. All seven counties voted against Kentucky GOP Sen. Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader, when he last ran for reelection in 2014. They all voted against Senator McConnell in his race before that, in 2008, as well.

But President Donald Trump swept the area in 2016. More than two-thirds of Morgan County voted Trump, for instance.

Some of the counties have gone Republican at the presidential level in the past, so in that sense weren’t a big surprise. But Elliott County had voted Democratic in every presidential ballot since the county was organized in 1869. It voted for President Barack Obama twice.

In 2016 Elliott County voted for Mr. Trump over Hillary Clinton by 70.1% to 25.9%.

“I’ve been a Democrat since I was old enough to register,” says Mike Reynolds, a maintenance lineman, as he finishes his lunch in the Frosty Freeze, a landmark in the town of Sandy Hook. “And I’ll vote for Trump again.”

Politics from another era

In Elliott County the biggest town is Sandy Hook, and in Sandy Hook, the biggest spot is the Frosty Freeze: a wood-paneled diner offering four varieties of fried potatoes. Diners filter in and out, greeting each other by their first names. It’s open seven days a week, 365 days a year, says Mr. Reynolds.

But he quickly corrects himself. Actually, he says to clarify, it’s closed on Christmas.

So, why did the few thousand residents of this small county vote against 147 years of tradition in 2016? The Obama era is what changed people, says Mr. Reynolds.

“The coal really hurt us, then throw guns and abortion in and it’s game over,” says Mr. Reynolds.

The area’s pipefitters and boilermakers are now also out of business, he says, with nearby factories closing in recent years.

As Mr. Reynolds talks about his recent voting history during his lunch break at the Frosty Freeze, it seems to parallel with Elliott County’s larger shift. In 2008 Mr. Reynolds voted for President Obama, who won more than 60% of the county that year. In 2012, unhappy with Obama’s first term but not ready to vote for a Republican, Mr. Reynolds decided not to vote as Mr. Obama eked out a second victory.

Then in 2016, for the first time in his life, Mr. Reynolds voted for a Republican presidential candidate. And Mr. Trump won Elliott County with 70% of the vote.

Atlas of U.S. Elections

It’s possible that the Trump explosion in a collection of counties where registered Democrats make up a substantial majority is evidence of a tectonic shift long masked by Kentucky’s complicated registration process. Voters have to register with a new party months before an election, for example. “Democrats” here may be Democrats only on paper.

It’s also possible that the political identity of many of eastern Kentucky’s conservative Democrats is grounded in another era. In the 1970s, Democrats in Congress voted against abortion at about the same rate as their Republican peers. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Democratic voters consistently supported access to abortion compared with Republican voters.

And when former President Bill Clinton passed gun reform bills in 1993 and 1994, requiring background checks for many purchases and banning assault rifles, respectively, 25% to 30% of House Democrats voted against the measures. Many of these lawmakers were “Blue Dog Democrats” – representatives of conservative districts, most of them rural and Southern or Middle American.

Socially conservative Democrats are rare in Congress – even the new Blue Dogs are centrists, rather than traditionalists. “They are certainly an endangered species,” says Al Cross, director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues at the University of Kentucky’s School of Journalism, and former chief political writer of the Louisville Courier Journal.

Eastern Kentucky’s partisan switch was also predictable, given that it had already taken place in every other Southern state, says Mr. Cross.

During the civil rights era, many Democratic Southerners disagreed with their party’s support of the issue and became Republicans. That dynamic never quite took hold in Kentucky, says Mr. Cross. He suspects it’s because of the all-white population of Kentucky in general, and eastern Kentucky in particularly. Desegregation simply wasn’t as big of an issue for them.

So it wasn’t until the Obama administration, “the most anti-coal administration in American history,” says Mr. Cross, that Kentucky and West Virginia (a state with even fewer people of color and even more coal) finally became ripe for the Republican picking.

Religion and votes

In eastern Kentucky these economic and social shifts were compounded by the 2016 election, when the Democratic Party picked Hillary Clinton as their presidential nominee – a choice Kentucky Democrats say they didn’t want. There wasn’t an alternative they liked better, they say, but it felt like the decision was forced on them. And much of their distrust and dislike of Mrs. Clinton circles back to the religious push behind their social views.

“No one here’s going to vote for a woman president,” says Lora Goodpaster while washing the color out of a woman’s hair at Heatwaves Salon in Bath. Bath, where almost 1 in 4 residents live in poverty, voted to uphold its status as a dry county in 2017.

“Getting your elderly convinced that women can go out and get power is hard when you have your preacher, who you respect, tell you the man is the head of the house,” says Ms. Goodpaster.

The other women in Heatwaves nod in agreement.

It’s not just Bath. Conservative Christian faith pulses throughout eastern Kentucky. Anti-abortion signs with Bible passages are staked across lawns in Elliott County and painted on barn doors in Nicholas County. In Rowan County, the side of one house says, “I’m watching you – God.”

“People here don’t approve of abortion for religious reasons,” says Mr. Kinner. “And they feel like they are looked down upon and belittled for those reasons.”

When Mr. Kinner talks about how West Liberty’s courthouse used to hold the town’s religious revivals, he almost sounds nostalgic. Today there seems to be a greater separation at the national level between church and state, say eastern Kentuckians. But Mr. Trump is helping to close that, they say.

“I vote for whoever votes for Christian values,” adds Dale Oakley, who helps manage Aunt Bubba’s for his daughter, the owner. “And right now, [Mr.] Trump is the only one who’s stood up for Christianity.”

The separation between faith and politics in today’s Democratic Party surprises, confuses – and then isolates – voters in eastern Kentucky. They are used to Democrats like Kentucky House of Representatives Minority Leader Rocky Adkins from Rowan County, who is a member of the Pro-Life Caucus and voted for several bills this year to restrict abortion. Mr. Adkins ran for governor this spring and lost in the Democratic primary by a few percentage points. But Mr. Adkins won all of eastern Kentucky, many counties by more than 70%.

Of Morgan, Nicholas, Bath, Menifee, Rowan, Elliott, and Wolfe, all but two have Democratic judge executives, the highest executive office at the county level in Kentucky.

“Locally, I vote for Democrats all the time,” says Mr. Oakley. “But I won’t vote for a Washington Democrat.”

‘We respect horse traders’

Eastern Kentuckians’ ideological mix of old Democratic Party and new Republican Party – its own unique DNA double helix – will make 2020 an interesting election for the state, when both President Trump and Senator McConnell will be up for reelection.

Mr. McConnell’s biggest threat in recent elections – besides the state’s two largest cities of Louisville and Lexington – has been the cluster of seven eastern counties. All voted against him the last two times he’s been on the ballot. They’ll remain an important focus for former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath, a prominent Democrat looking to unseat the Senate majority leader.

“If I were [Mr.] McConnell, I would be incredibly scared about that area,” says Ryan Aquilina, founder of the anti-McConnell political action committee Ditch Mitch.

But Mr. McConnell will likely be fine, considering he will be on the Republican ballot with Mr. Trump. As for the president’s chances himself in 2020, dozens of eastern Kentuckians interviewed for this article were asked if they would vote to reelect President Trump. They all said “yes,” and they all said “yes” emphatically. Some even answered before the question was asked.

Knowing the area, Mr. Kinner isn’t surprised about Mr. Trump’s support. He says the president is like a Kentucky horse trader: He drives a hard bargain, and sometimes that means being loud and bluffing.

“My dad said the people here are the salt of the earth, but be careful trading with them cause they’ll take you to the cleaners,” says Mr. Kinner. “We respect horse traders.”

Atlas of U.S. Elections

Farmers grow the food. But who’s helping new farmers put down roots?

How do you marry ambition (and no money) with experience? Our reporter looks at initiatives for helping the next generation of farmers, including a matchmaker program for beginners and old hands. Part 1 of 3.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Jennifer T. Sharrock left an insurance career this year to pursue market farming and permaculture full time in Palmer, Alaska. The beginning farmer started teaching permaculture design three years ago, but her popular classes quickly outgrew her space. Buying more land wasn’t financially feasible.

So she placed an ad in Alaska Farmland Trust’s FarmLink program, a kind of “dating service” for land seekers and owners. That’s when Jan Newman, a neighbor with unfarmed land, answered her ad. “It’s a match made in heaven,” says Ms. Sharrock. She gets to expand her business, and Ms. Newman avoids the time and expense of maintaining the land herself as she faces retirement.

As the average age of the U.S. farmer has climbed to 57.5, farmable land is poised for a dramatic change of hands.

But along with access to capital, access to land is one of the greatest hurdles faced by beginning producers. Land-link pairings like the one in Palmer represent one possible step toward solving a nationwide puzzle – how to help experienced farmers exit agriculture while building an on-ramp for new producers.

Farmers grow the food. But who’s helping new farmers put down roots?

Jan Newman became an accidental alpaca farmer. She took up knitting in the 1990s at home in Palmer, Alaska, to supply her first child with natural-fiber clothing, and one thing led to another. She innovated again in 2013 when she founded Grow Palmer, a public food program that plants edible gardens around town. These days, Ms. Newman is pondering retirement.

“It’s not an easy transition to consider selling the farm,” she says.

Jennifer T. Sharrock is just starting out. She left an insurance career this year to pursue market farming and permaculture full time through her Seeds and Soil Farm. The beginning farmer began teaching permaculture design three years ago, but her popular classes quickly outgrew her space. Buying more land wasn’t financially feasible.

So she placed an ad in Alaska Farmland Trust’s FarmLink program, a kind of “dating service” for land seekers and owners. When Ms. Sharrock received an answer to her ad, her heart skipped a beat. She saw it was from Ms. Newman, whom she’d met through Grow Palmer. They also turned out to be neighbors.

“It’s a match made in heaven,” said Ms. Sharrock, who has started on four acres of Ms. Newman’s property.

It’s a win-win for both women. Ms. Sharrock gets to regenerate land through permaculture design that could eventually yield a rainbow’s array of produce. As a trade, Ms. Newman gets to take classes with Ms. Sharrock, and avoids the time and expense of maintaining the land herself.

“There’s actually no money changing hands,” says Ms. Newman, who calls the younger farmer’s regenerative agriculture plan “the best stewardship possible.”

“Anything that Jennifer and her cohorts develop over there is only going to improve my property,” she says.

Land-link pairings like the one in Palmer represent one possible step toward solving a nationwide puzzle – how to help experienced farmers exit out of agriculture while building an on-ramp for new producers.

In the past two decades, the United States has lost about 8% of its farms and the only operations that have bucked that trend are the very largest (2,000 acres or more) and the very smallest (less than 50 acres). That persistence of small farms is significant, because the majority of those operations are run by beginning farmers. And from the prairie states to Alaska and Maine, some are finding creative ways to succeed.

“I get a sense there are more young people who don’t necessarily have farm backgrounds, who are taking agriculture entrepreneur courses, and they are starting to jump into farming,” says Jim MacDonald, an economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Along with access to capital, access to land is one of the greatest hurdles faced by beginning producers in the United States. One sign of the barriers to entry: The average U.S. farmer’s age has taken a long-term climb over the past several decades, now reaching 57.5, according to the USDA’s latest census figures. While there has been some increase in the number of producers under age 35 – partly due to how the census now defines them – this group remains vastly outnumbered.

But while farmable land is poised for a dramatic change of hands over the next few years, some agriculture experts see fertile soil for American ingenuity through shared resources and wisdom.

“As someone retires, that’s an opportunity for two or three other young people. There’s no shortage of people that want to farm,” says Michael Langemeier, an agricultural economics professor at Purdue University in Indiana.

Looking for land

USDA defines beginning farmers and ranchers as having no more than a decade of experience. This group makes up 27% of the country’s 3.4 million producers, and with an average age of 46, they aren’t that young. In Alaska, 46% of the state’s producers are beginners – the largest share of any state. Amy Pettit, executive director of Alaska Farmland Trust, says the demand for more locally grown food is one of the factors pulling new farmers north.

“If you want to grow something here, there’s somebody to buy it,” says Ms. Pettit. “If you had some sense of wanting to be a farmer, this is a great place to do it.”

But buying land for many new farmers remains out of reach. A National Young Farmers Coalition survey reported land access was the No. 1 challenge faced by aspiring farmers and those who’ve left farming. Farmland real estate values, which includes land and the structures on it, have risen sharply since 2000. Prohibitive costs have meant beginners often rent land before they try to buy. Cropland rent averaged $138 per acre in 2018 with wide regional variance; California has the highest average cropland rent at $340.

Land availability is another concern. A study by American Farmland Trust found that between 1992 and 2012, the U.S. converted almost 31 million acres of agricultural land to development – a loss the size of New York state. Foreign investors hold around 30 million acres of farmland.

“There is a sense of urgency,” says Tim Biello, who coordinates the Hudson Valley Farmlink Network in New York. “The history of our use of agricultural lands suggests that we’re not getting more.”

Securing soil for the next generation

Land-link programs first launched after the wide-scale farm bust of the 1980s. Kathy Ruhf, a land access expert and senior adviser at Land for Good, says they formed in response to a lack of family successors for aging farmers.

Around 50 land-link programs are still at work across the country. Unlike Ms. Sharrock and Ms. Newman’s arrangement, most land links involve a financial transaction like a sale or lease. While these programs vary in scope and success – offering a variety of services led by nonprofits, land trusts, universities, and state governments – the most effective models prioritize the transfer of knowledge and long-term business and retirement planning. When land links involve person-to-person resources, experts say, all parties involved are better equipped to address the challenges of growing the next generation of American farmers.

“The definition of a farm link program needs to be broader than an online database that results in matches,” says Ms. Ruhf, noting that matches are rare. “Most farm link programs have some kind of educational component and technical assistance.”

Launched by the American Farmland Trust, Hudson Valley Farmlink Network is among the most active, with 175 matches since 2014. Mr. Biello, the network’s coordinator, attributes the success to individual attention and relying on the localized expertise of 17 partner organizations. Before a user’s profile is activated on the farmland finder site, the individual must have a phone call with a staff member to review their profile and discuss their farming plans.

Mr. Biello says that matches shouldn’t be the only metric for measuring a land-link program’s impact. He points instead to the trainings, events, and one-on-one assistance that have reached more than 10,000 farmers and farmland owners.

“Those are really important data points, because they show that by having this group of partners who can do this work together, focus in the same direction – it really allows for pretty big impact,” said Mr. Biello.

California FarmLink, another well-established program active since 1999, requires land seekers to have two or more years of experience along with a current decision-making role on a farm or ranch.

“By the time they’ve gotten to us with that first 10-acre lease or $10,000 loan, they’ve got sort of a track record under their belt,” says Reggie Knox, California FarmLink’s executive director. He says good planning is key to “make sure everything’s clear about who pays for what when the pump breaks down in the well.”

Land-link programs can help farmers secure necessary funds, too – often a first step before even beginning an operation.

“Any lender wants to see a copy of your lease to make sure you have the land security during the period of the loan,” says Mr. Knox. California FarmLink helps facilitate around 50 loans a year, in addition to around 45 leases or land purchases. As a community development financial institution, California FarmLink especially strives to reach low-income farmers through loans for small and mid-sized farms.

In Palmer, Alaska, Ms. Sharrock recently covered the four-acre field with large silage tarps to kill off unwanted growth for a year. She is banking on a diversified income stream that includes farm and seed sales, permaculture classes, and garden coaching.

Ms. Newman hopes the new farmer will remain on the land long term.

“I just can’t wait to see this evolve,” says Ms. Newman. “It’s the most exciting thing that’s happened on the property since our alpacas left.”

Monitor staff writer Laurent Belsie contributed to this report.

This series focuses on solutions to challenges faced by beginning farmers. The other installments include Part 1: What if aspiring farmers have no money for a farm? Part 2: How a Maine network is helping beginning farmers stay in the business. Part 3: Entrepreneurial approaches breathe new life into the family farm.

With his oud, this musician transports audiences

Rahim AlHaj, who has been twice nominated for Grammys, uses his music to build empathy for those living with conflict in Iraq and elsewhere.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Stephen Franklin Round Earth Media

Rahim AlHaj's music career was launched in second grade when his teacher in Baghdad brought an oud to class and let him take the pear-shaped stringed instrument home on the condition that he take lessons. “I put my hand on this beautiful oud and the electricity came to me,” he recalls.

As a teenager, he composed a song that was regarded as critical of Saddam Hussein’s rule. Targeted as an enemy of the regime at age 17, he served time in prison and eventually fled Iraq for Jordan after the first Gulf War. At the border, the childhood oud was confiscated because he lacked permission to take it out of the country.

He has since gained a new country – the U.S. – and a new oud. The two-time Grammy nominee is focused on making music he hopes will help audiences understand the plight of those in Iraq and elsewhere.

Tesbih Habbal, a young Syrian who heard him play in Chicago recently, says the music reminded her of home and the tragedy taking place there. “It was a mixture of sadness and despair and hope in something,” she says. “Sometimes through such experiences you can create a beautiful thing.”

With his oud, this musician transports audiences

Rahim AlHaj knows about loss. He knows about losing his country and losing the beloved musical instrument that set him on his life’s path. The distress of fellow Iraqis still cuts deeply. But he is driven to promote peace and empathy in a new home thousands of miles away.

His voice is the oud, a pear-shaped ancestor of the lute, mandolin, and other stringed instruments.

At a recent concert here, a large painting splashed in red depicts a boy whose home in Baghdad has just been destroyed by a car bomb. The pigeons he nurtured have flown away. Mr. AlHaj, accompanied by five classical musicians and a cajon (box drum) player, express the boy’s loss with music that builds a swelling sense of melancholy.

In one sad moment, the oud seems as though it is reciting a prayer. And Mr. AlHaj seems as though he may be crying.

The music, from the 2017 album “Letters from Iraq,” is deeply personal for Mr. AlHaj. Its message about the suffering of Iraqis and others around the world is so urgent for him that he is continuing to tour it this year in cities such as Chicago, Austin, and Iowa City, despite a wealth of other projects and a subsequent album, “One Sky,” released last year.

Mr. AlHaj has embraced far more than loss since coming to the United States 19 years ago as a political refugee from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. He has become an advocate for those who have suffered from war, and like himself, tumbled into homelessness. At a time when migration is one of the hottest issues in his new homeland, he speaks out firmly on behalf of immigrants.

“I’m a man with a mission, and we have only so much time,” says Mr. AlHaj moments before his concert at the University of Chicago. His mission, he explains to the audience, “is about human rights and how this planet needs to be nurtured as a gift for our children.”

‘Rooted in deep emotions’

Mr. AlHaj has made an impact. He has performed on 12 albums, twice been nominated for a Grammy, and received a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He has melded his music with Iranian and Indian performers, written compositions for orchestras, played with the band R.E.M. and jazz groups, and joined in performances and a CD with a group that promotes bonds across the U.S-Mexico border.

Atesh Sonneborn, a former associate director of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, says Mr. AlHaj’s synthesis of Pan-Arabic and Western music is powerful. “My take is that it is rooted in deep emotions, and something we call the heart,” he says.

Despite many setbacks, Mr. AlHaj marvels at his good fortune.

It started in Baghdad, when his second-grade teacher brought an oud to class. “I put my hand on this beautiful oud and the electricity came to me,” he recalls. The teacher let him take it home, and the next day allowed him to keep it on the condition that he take formal classes, which he did.

As a teenager, he composed a song that was interpreted as being critical of Mr. Hussein’s rule. Targeted as an enemy of the regime at 17 years old, he served two terms in prison, for a total of two years. He doesn’t talk much about prison except to say he saw a friend killed, and that he suffered torture.

He fled Iraq for Jordan with fake identification papers after the first Gulf War, but at the border the oud he had clutched from childhood was confiscated because he lacked permission to take it out of the country. He calls that his most painful loss. Fearful of Iraqi agents, he soon moved to Syria, where his musical career flourished.

After years of waiting, he was accepted by the U.S. as a political refugee, and given only two days to prepare to leave. He wound up in Albuquerque, where a social worker told him he would be working at a McDonald’s.

“I said, What kind of conservatory is that? My second instrument is a violin.”

He didn’t take the job and mulled going home. He was working as a night watchman when a friend offered to help pay for a recording. He figured he could raise enough money from it to return to Syria.

They only had enough money for one hour of recording time, and so he made the album, “The Second Baghdad,” with no retakes. That first album led to gigs around Albuquerque. At one, he met then-Columbia University music professor Steven Feld, who invited him to come to Columbia to perform. The 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq had just begun. Mr. Feld helped him record his second album, ”Iraq Music in a Time of War.”

“The way he introduces each piece and the music really gives you a window into the mind of somebody who has experienced multiple wars and tragedies, but also reaches out to the deep side of music to come out whole,” says Mr. Feld.

His initial albums were solos, but then Mr. AlHaj started to compose and collaborate. He also realized that he had found a home in Albuquerque, and that he needed to tell the story of others still searching for theirs.

“I’m obsessed about music and arts, except that I have a zillion things to do in this country to make a difference,” he says, adding how American he feels because of his love for the country and how hard he has worked. Every year on March 21, the anniversary of his arrival in the U.S., he celebrates with a special concert.

He also conducts workshops and sessions with younger audiences in which he explains his music and what it was like to grow up in Iraq. In Chicago, he spent two days going to public schools, some in low-income, African American, and Latino communities.

As a refugee himself, he speaks out forcefully for immigrants. “Immigration makes any country more powerful and advanced and greater,” he says. “We need not just doctors and musicians. We need everyone.”

Yet his bonds to Iraq run deep, and “Letters from Iraq” illustrates that.

Influential correspondence

Visiting Baghdad in 2015, he was moved by a letter in which his disabled nephew told how he narrowly escaped death in a bombing at the height of Iraq’s sectarian violence.

“I was in tears,” Mr. AlHaj recalls.

He went about collecting other letters and used them in a lecture showing Americans what Iraqi women and children had endured. But he felt he needed to do more. So he composed the album, which later included illustrations by Iraqi artist Riyadh Neama that are used as a backdrop for Mr. AlHaj’s concerts.

On stage here for his presentation of “Letters from Iraq,” Mr. AlHaj was joined by three violinists, a bass, a cello, and the cajon player. A small, thin man with an expressive smile, Mr. AlHaj chatted casually and joked with the audience before performing.

But when the performance began, he became somber, leading the players with his eyebrows, a nod, or smile. The sweep of the music was classical Western, with Mr. AlHaj stepping in and out with his oud to lead the way.

At a reception afterward, an Iraqi university student who had only arrived a year ago in the U.S. said he wished that the music had been more traditional, and that it had not been so sad. A Kurdish musician from northern Iraq wished that there had been some music pointing to Kurds’ suffering in Iraq.

Others heard something else.

“I felt like it was one long meditation because of the profound effect on me,” says audience member Tamara LaVille. It surprised her, she adds, that the “oud was almost a hushed bystander.”

Tesbih Habbal, a young Syrian from Aleppo who left her country in 2013, says the music reminded her of home and the tragedy taking place there. “It was a mixture of sadness and despair and hope in something,” she says. “Sometimes through such experiences you can create a beautiful thing.”

This story was produced in association with the Round Earth Media program of the International Women’s Media Foundation.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Soft path to a hard peace in Afghanistan

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

If forgiveness is key to ending a conflict, then the long war in Afghanistan just saw a merciful ray of hope. Taliban and Afghan officials have held talks for the first time, even issuing a joint “road map” toward national reconciliation. Yet with the hard details still to be negotiated, it was the moments of softhearted sharing that may have set the tone for reaching a final deal.

During the talks in Qatar, the two sides recognized the mutual suffering of others in the room as a result of the ongoing 18-year war. They told tales of relatives and friends lost to either Taliban attacks, U.S.-led airstrikes, or imprisonment. The sharing of personal sorrow set a mood of contrition and an opening for compromise. The joint statement stressed that all of Afghanistan is “suffering daily.”

They are a long way from finding common ground on basic issues of governance, women’s rights, and the role of other countries in Afghanistan. Yet this intra-Afghan negotiation has broken ground on essential virtues necessary for an agreement.

Soft path to a hard peace in Afghanistan

If forgiveness is key to ending a conflict, then the long war in Afghanistan just saw a merciful ray of hope. On Sunday and Monday, Taliban and Afghan officials held talks for the first time, even issuing a joint “road map” toward national reconciliation. Yet with the hard details still to be negotiated, it was the moments of softhearted sharing that may have set the tone for reaching a final deal.

During the talks in Qatar, more than 50 Afghan politicians and civil society activists and 17 Taliban members recognized the mutual suffering of others in the room as a result of the ongoing 18-year war. They told tales of relatives and friends lost to either Taliban attacks, U.S.-led airstrikes, or imprisonment. The sharing of personal sorrow set a mood of contrition and an opening for compromise. The joint statement stressed that all of Afghanistan is “suffering daily.”

Nader Nadery, chairman of the Afghan civil service commission, said he acknowledged the suffering of Taliban officials who had been held for years in detention. “I have the courage to forgive, as I know your members have suffered, too,” he told the group.

Many wept at the stories. “The pain from all sides, whether it is the night raids or the bombings, that is why we are here,” Suhail Shaheen, a member of the Taliban delegation, told The New York Times.

Such tender moments may help dispel the mistrust, fear, and hatred that drive the war. As often happens in negotiations to end armed conflicts, the two sides found some empathy. According to participants, there was great patience in listening to each story. Their newfound vulnerability and humility may yet create a capacity to forgive the violence of the past and move toward peace.

The two sides are a long way from finding common ground on basic issues of governance, women’s rights, and the role of other countries in Afghanistan. A parallel set of talks between the Taliban and the United States has made more progress. Yet this intra-Afghan negotiation has broken ground on essential virtues necessary for an agreement. “It is not easy for me to sit across from people who have killed my father,” said Abdul Matin Bek, an Afghan Cabinet member, according to the Times. Yet in a sign of forgiveness at work, he added, “But we have to end this.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The rule of a higher law in Hong Kong

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Dilshad Khambatta Eames

There’s no easy solution to the troubles in Hong Kong and elsewhere in the world. But here’s a spiritual take on the idea of government and the potential it holds for humanity, inspired by a prayer one woman first learned while living in Hong Kong.

The rule of a higher law in Hong Kong

Twenty-two years ago, while living in Hong Kong, I watched the historic handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to China. There was much rejoicing among some of my local friends. Hong Kong was a thriving economy, and people felt connected to their Chinese roots. A new government of “one country, two systems” seemed a good way forward to many. Others felt the need to relocate to countries where the government was securely and historically democratic. And then there were those in between, who preferred to stay and wait, keeping their options open.

Recent events in response to what many see as a tightening of Chinese control of Hong Kong have motivated me to pray about this situation. In particular, there has been use of the term “rule of law” by the Hong Kong government. But many of the protesters see Chinese law – which some Hong Kong citizens could have been subject to had a controversial proposed law been passed – as not impartially applied.

My prayers have been inspired by a short “Daily Prayer” that I learned about when I was introduced to the healing practice of Christian Science while living in Hong Kong. The prayer was written by the discoverer of Christian Science and founder of this newspaper, Mary Baker Eddy, who saw the need for prayer to be unselfish and radiate outward to bless all humanity. It speaks of a unity found under the rule of a higher law – divine law: “‘Thy kingdom come;’ let the reign of divine Truth, Life, and Love be established in me, and rule out of me all sin; and may Thy Word enrich the affections of all mankind, and govern them!” (“Manual of The Mother Church,” p. 41).

I saw this as a directive for me as an individual to play a role. I was being asked to let myself be governed by God – divine Life, Truth, and Love – and also acknowledge that God’s Word embraces all. It was indeed a prayer of the power of unity, of the rule of Love that is so infinite it can benignly touch the hearts of each and every one on the planet.

As one begins to explore this, one also begins to see that true “affection” is rooted in the supreme law of Love, or God. The word “God” conjures up a variety of feelings and associations for folks in Hong Kong, based on perceptions, backgrounds, personal experiences, et cetera. But Christian Science offers an understanding of God as entirely good, whose divine law is so all-encompassing that one can refer to God as “the all-knowing, all-seeing, all-acting, all-wise, all-loving, and eternal,” as the definition of “God” in Mrs. Eddy’s book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” says (p. 587).

God’s law is universal, so each of us has an innate ability to mentally discern and yield to divine Love, which I have found brings freedom and healing. It also opens our hearts to glimpse and feel the true nature of everyone – including protesters and government officials – as spiritual and pure, the image and likeness of God, as the Bible teaches.

This empowers us to see our fellow brothers and sisters as able to act with God-given moral courage, wisdom, foresight, sincerity, love, honesty, and understanding. Where such qualities are present, chaos, strife, fear, and insecurity are lessened.

Science and Health explains, “Reflecting God’s government, man is self-governed” (p. 125). There’s no easy solution to the concerns in Hong Kong and elsewhere in the world. But each of us can start with a selfless, loving prayer: a humble willingness to yield individually to the rule of God’s law, the law of good, and by doing so accept that others have, and will always have, access to the spiritual freedom we can all find under God’s government.

A message of love

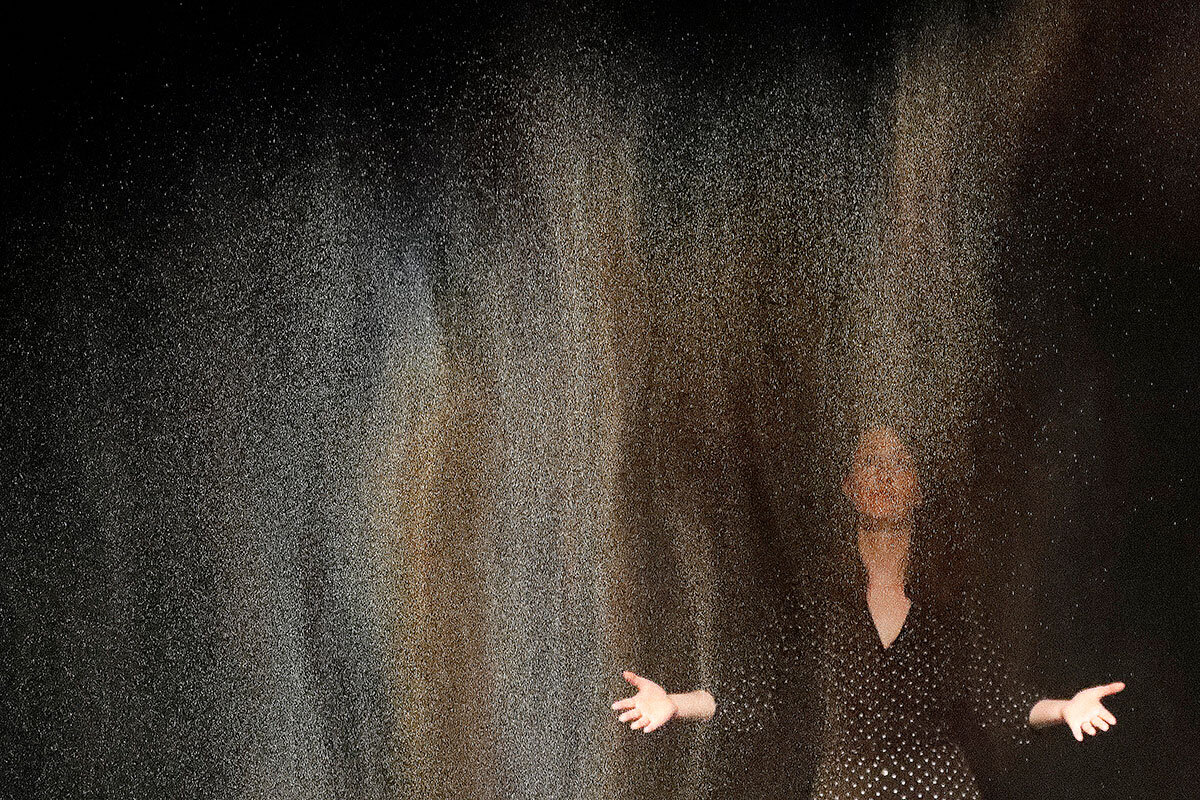

Watercolor

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about the mayor of Huntington, West Virginia, who’s created a new model for tackling the opioid crisis.