The closer that economists look at the rise in income inequality, the more they find one cause may be the rise of another inequality: The least productive firms are falling further behind the most productive firms. The Kmarts of the business world aren’t keeping up with the Googles. And one reason is a widening gap in innovation, creativity, and, more fundamentally, a curiosity to discover and embrace new ideas.

This point was made in a recent study spanning 16 countries by the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. It found the “productivity gap” between firms in the top 10 percent by productivity and those in the bottom 10 percent rose by about 14 percent from 2001 to 2012.

“The corporate landscape has become increasingly unequal,” the three authors of the study write in a Harvard Business Review article. “This matters not just for economic growth but also for [pay] inequality.”

Most companies try to increase the quality and quantity of their workers’ output, or what is called the productivity rate. As Janet Yellen, chair of the Federal Reserve, often tells Congress and others, productivity growth “is what really determines in the long run the pace of [economic] growth.”

But individual companies can fall behind competitors if they lag in their flexibility to change and their openness to new technologies or fresh ideas in workplace management. The traits of highly productive firms require that staff have boundless motivation to learn and adapt. In short, people must keep asking questions.

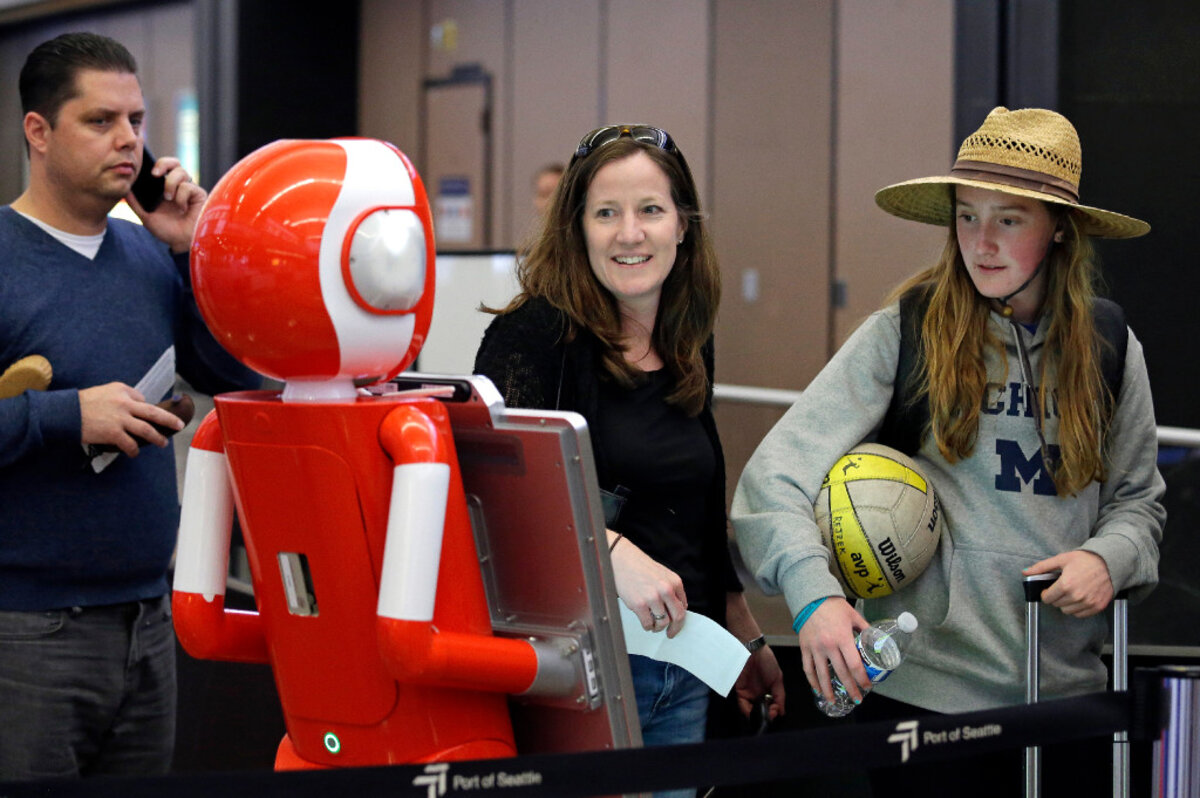

By their very desire to understand and cope with the world, humans ask questions. Computers, on the other hand, must be guided to do so and are given goals or limits. Companies certainly must tap artificial intelligence (AI) or machine-learning robots to raise productivity. Automation helps overcome human bias or limits. AI can perceive opportunities in “big data.” But it cannot replace human inquisitiveness, or the impulse to ask “why.”

Companies and workers looking to raise their productivity – by boosting curiosity – may be helped by a new book, “Why?: What Makes Us Curious,” by famed astrophysicist Mario Livio. He worked on the Hubble Space Telescope and the window it opened to the cosmos. This led him to become curious about curiosity, starting with humanity’s early spiritual quest for meaning.

His book explores the limited research on curiosity and dives into the lives of inventive people, such as Leonardo da Vinci. Dr. Livio found curiosity can be divided into two types: one that seeks to solve problems and the other that loves understanding just for the joy of it. In the first, curiosity is a cure for fear. The second opens even more questions and leads to new discoveries.

Sometimes the two combine. “Love of knowledge does create a reward for its own sake, but you want to feel results,” he writes. “

Curiosity is self-sustaining because it keeps unfolding ever-more truths. "Curiosity’s powers extend above and beyond its perceived potential contributions to usefulness or benefits. It has shown itself to be an unstoppable drive,” the book states.

Yet not all curiosity is welcomed. Parents must guard what children learn. We speak of morbid curiosity, such as gawking at a car accident. Or “curiosity killed the cat,” as in getting too close to danger. Under a dictatorship, leaders try to suppress the flow of ideas or demand conformity. In such countries, creativity and productivity can falter.

The constant desire to ask “why” is what distinguishes humans from animals and robots. Curiosity and the intelligence it brings is also essential for innovation in business. And now, because of the inquiring minds of academics, we know it can also be one of the many ways to help reduce economic inequality.