Ukraine needs the long arm of the law

Loading...

Far more than the people of Ukraine took notice on Sunday when a young and prominent anti-corruption activist, Kateryna Handzyuk, died in Kiev after an acid attack.

While protests were quickly held in five cities demanding her killers be held to account, it was the strong reactions in Washington and European capitals that mattered more – mainly because Ukraine has become a test case of whether foreign pressure can help end entrenched corruption in a sovereign country.

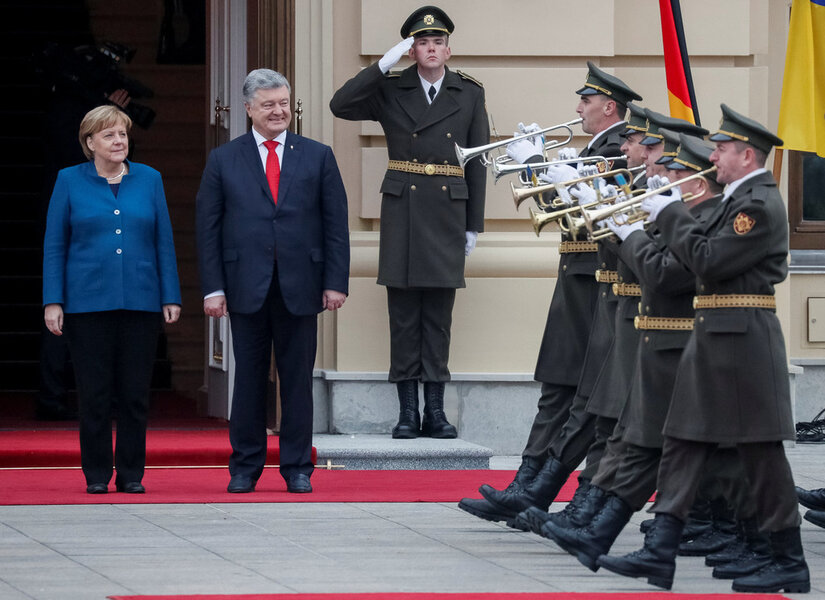

Ever since a pro-democracy revolution four years ago, Ukraine has been on the front line of the West’s struggle with Russia and its brand of authoritarian rule. Kremlin-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine are trying to split the country. Yet the West has also withheld critical financial aid to the government of President Petro Poroshenko until it implements anti-corruption reforms, such as starting a special court to deal with high-level graft. It would be useless to let Ukraine enter the European Union, as it wishes to do, if it is rotting within from greedy officials.

The killing of Ms. Handzyuk, along with dozens of attacks on similar activists, shows the West now needs better tools to influence Ukraine and other countries in the growing global fight for clean governance. Corruption on a grand scale like that in Ukraine is often a source of civic unrest, terrorism, drug trafficking, and many other problems that often leap across borders.

Yet even as corruption seems to be advancing in many countries, so has popular indignation. “People around the world, particularly young people, no longer accept grand corruption as an inevitable fact of life,” writes United States federal Judge Mark Wolf in the latest edition of the journal Daedalus.

Since 2014, Judge Wolf has been the leading advocate for the creation of an international anti-corruption court. Such an impartial tribunal, similar to the current International Criminal Court (ICC), would put a country’s officials on trial if that country is unwilling or unable to make good-faith efforts to probe and punish them.

The impact of such a court on corruption, contends Wolf, would be “even greater than the ICC’s impact on violations of human rights.” One example of how the long arm of the law can reach across borders is a unique legal tool in the United States, the 1977 Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. The US has used the law to prosecute foreign businesses and officials, not just Americans. The act has spurred many countries to adopt international codes aimed at curbing corruption.

The desire for honest, transparent, and accountable government knows no bounds. The people of Ukraine want and need help to oust corrupt leaders. With activists willing to sacrifice for this cause, the rest of the world can do more.