Africa eyes a new path to clean governance

Loading...

Africa’s leaders ended a summit Jan. 29 with a new statistic on their thoughts: By 2063, the continent will see a tripling of the number of working-age people, to nearly 2 billion. The increase will far surpass the increase in all of Asia, India, and China. To create jobs for Africa’s coming population bulge, the leaders decided to focus their efforts this year on the one big obstacle to economic growth: corruption.

Each year Africa loses about a quarter of its gross domestic product to corruption, either in petty bribes or wholesale looting of natural resources. This injustice, says Vera Songwe, head of the Economic Commission for Africa, “is more powerful than any other injustice we as Africans could face.” The best evidence of the problem is the fact that an estimated 200,000 Africans are currently attempting to cross the Mediterranean to reach Europe.

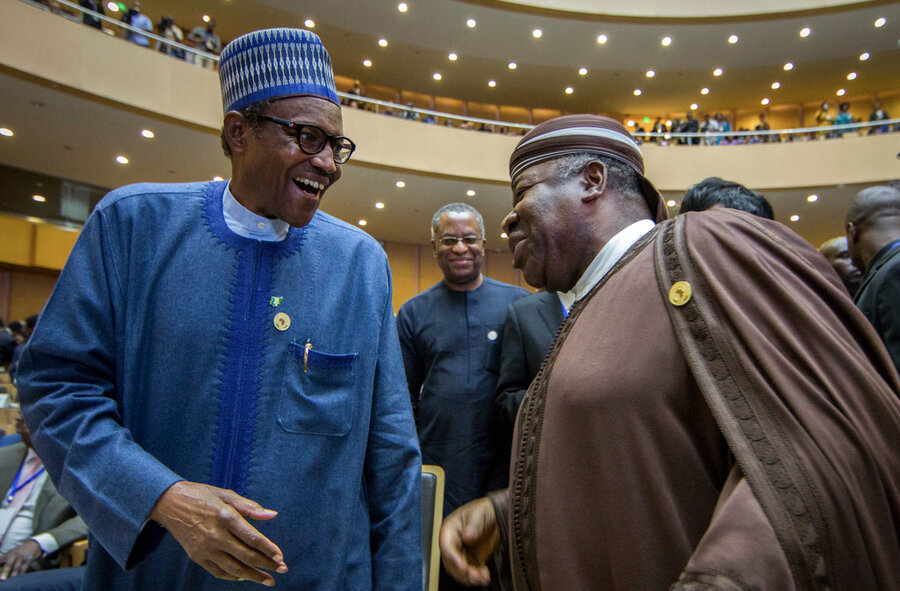

To tackle the issue, the 55-nation African Union named Nigeria’s president, Muhammadu Buhari, the AU’s first anti-corruption crusader. Mr. Buhari told the summit he will primarily enlist young people in a grass-roots campaign that demands transparency and accountability in government.

“To win the fight against corruption,” he said, “we must have a change of mind-set.” Reforms in governance alone, such as better watchdog agencies or independent judges, are not enough.

Buhari was selected because he seems to be one of Africa’s more sincere anti-corruption leaders. Elected in 2015, he has begun to bring some integrity into Nigeria’s institutions. He has far to go. Other leaders say a bottom-up approach is needed.

One effort is a new activist group, the People’s Grassroots Association for Corruption-Free Nigeria, which was launched in January. It plans to encourage people to see themselves as agents of change. Or as Thuli Madonsela, South Africa’s former lead public prosecutor puts it, the public must understand and be players in public accountability.

A recent survey by London-based Chatham House and the University of Pennsylvania found that Nigerians frequently underestimate the extent to which fellow citizens believe corruption to be wrong. It is not enough to simply change individual beliefs. If people were made more aware of how commonly held their moral beliefs are, “they would be more motivated to act collectively against corruption,” the report stated.

“Social norms drive the solicitation of bribes by law enforcement officials, whereas the giving of bribes is influenced more by circumstances and by people’s beliefs about what other people are doing,” the report said.

The current lack of confidence in official institutions has weakened Nigeria’s national identity, which should be based on the universal application of a fair and neutral rule of law. Instead, states the report, “less effective social contracts are forged particularly around ethnic or religious identities – an arrangement that fuels inter-communal distrust.”

Any government-led campaign against corruption, it concluded, will only be perceived as sincere if it is “self-examining and self-correcting.” Nigeria may have started down that road. Now the rest of Africa, at least by the signals from the latest AU summit, plans to get on that bandwagon.