Look again at Vincent van Gogh

Loading...

| Alameda, Calif.

In 1889, two weeks after voluntarily admitting himself to Saint-Rémy's psychiatric hospital in southern France, Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo from his asylum room: "Through the iron-barred window I see a square field of wheat in an enclosure ... above which I see the morning sun rising in all its glory." He remained in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence for a year, producing more than 140 paintings.

He suffered from what both he and the asylum director described as epilepsy, yet today we still read comments about Van Gogh's "madness." Indeed, the true light of his work has often been darkened by the shadow of insanity. Museumgoers may miss the spiritual import of a painting such as "The Raising of Lazarus" if they think of the artist primarily as someone disturbed enough to harm his own ear.

So it's welcome news that two German art historians have brought into question the self-mutilation claim. They speculate that rival artist Paul Gauguin cut Van Gogh's ear with a sword. Their revisionist claim gives us an opportunity to revise our own estimate of Van Gogh's work.

Certainly there were periods of debilitating crises for Van Gogh, of depression and loneliness, as well. His was an emotional intensity, a highly developed sensitivity – pure concentrated orange juice, one might say, that both attracted and frightened his friends. But mad? Never. Diagnoses aside, his paintings and letters reveal periods of great lucidity.

Many of his most inspired paintings and drawings from Saint-Rémy were conceived and produced inside this asylum, most frequently inside his small bedroom cell or studio room with only an iron-barred window to view the outside world. From his bedroom window facing southeast, he could see the sun rise over a vast expanse of wheat fields and the undulating shape of the Alpilles mountain range beyond. At night or in the very early morning before sunrise, he could see this countryside with "nothing but the morning star, which looked very big."

When painting these views, however, Van Gogh eliminated all references to "the iron-barred window." The window and its bars just disappeared. What remained were vibrant images of wheat fields in different seasons, of men plowing the furrowed ground and reaping the yellow wheat. Or images seen from his window combined with those remembered from his youth – a brilliant starry sky above the slopes of the Alpilles and a small Dutch church with its elongated spire nestled into the center of a village. Van Gogh refused to let asylum bars define who he was and what he saw. Rather, he honed his talent in the midst of these circumstances.

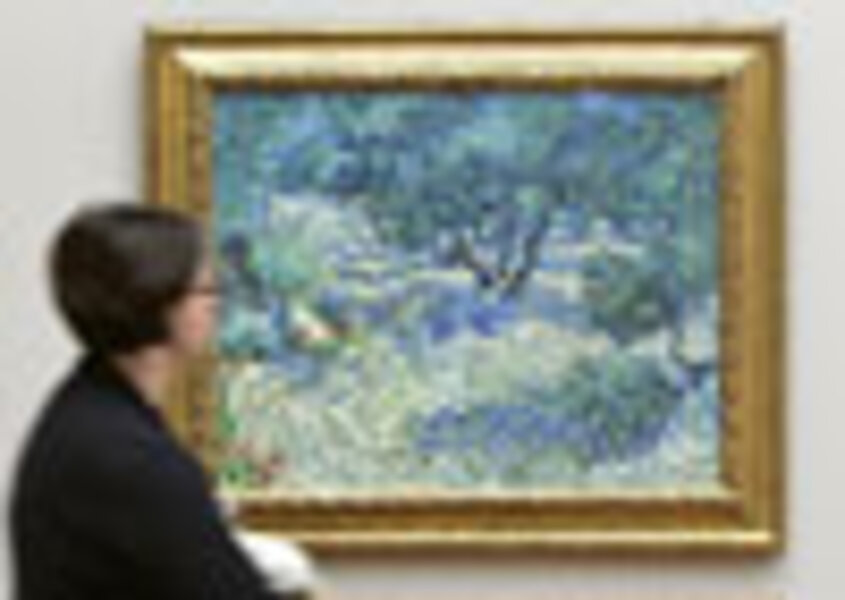

When allowed to paint outdoors, Van Gogh captured the very essence of his surroundings. His acute sensitivity to the land enabled him to distill the physiognomy of this unusual landscape. Here place and character commingled. Taken together, the "place" of Saint-Rémy and the "character" of Van Gogh yielded a highly concentrated and inspired vision. Those unfamiliar with this landscape see the tortuous shapes in his paintings as signs of a tortured mind. In fact, these strange, swirling, twisted shapes belong to the natural surroundings. His vision, undeniably marked by a distinctly personal style, was still rooted in reality.

Today when walking the asylum grounds, especially during the fierce mistral windstorms, visitors can actually feel the natural forces that reshaped the twisted cypresses and gnarled olive trees. Hiking up the craggy, barren slopes of the Alpilles to that strange dramatic geological formation called "Les Deux Trous" (Two-Holes Rock), they can see how nature reshaped these rocks long before Van Gogh ever painted them. You are reminded why this artist's dense, heavy brush strokes might be required. It is as if in the midst of such powerful natural forces, strong gestures were needed to anchor the paint to the canvas.

When illness struck and he was unable to work, Van Gogh found the atmosphere in the asylum especially "stupefying." The monotony of the place bore down on him, and he needed even greater mental exertion to rouse himself after such a crisis. He observed that the "company of all these unfortunates, who do absolutely nothing all day long, is enervating."

To reinvigorate himself, he asked his brother to send reproductions of works by artists he admired – Rembrandt, Delacroix, Millet, among others. He made copies – "translations," he would call them – of their works that he hung on his bedroom wall. Because these reproductions contained figures, they served as the studio models he could not have. But they were more than surrogates. He compared his translations to a violinist's interpretation of Beethoven: "I let the black and white by Delacroix or Millet or something made after their work pose for me as a subject. And then I improvise color on it, not, you understand, altogether myself, but searching for memories of their pictures – but the memory, 'the vague consonance of colors which are at least right in feeling' – that is my own interpretation.... I find that it teaches me things, and above all it sometimes gives me consolation. And then my brush goes between my fingers as a bow would on the violin, and absolutely for my own pleasure."

The above quotation from a Sept. 19, 1889, letter to Theo merely hints at this artist's extraordinarily lucid insights. His is a lucidity that we continue to see.

Jeanne Colette Collester, a former professor of art history at Principia College in Elsah, Ill., is the author of "Rudolph Ganz – A Musical Pioneer."