AP African American Studies: ‘Academic legitimacy’ or ‘indoctrination’?

Loading...

Last week, when Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis explained his rejection of a proposed Advanced Placement African American Studies class, I thought about the small number of Black students enrolled in AP courses. A 2020 report by The Education Trust pegged it at 9%, despite counting 15% of high school students nationwide as Black.

I was one of those few Black students 20 years ago. More often than not, I was the only African American kid in my class, the social ramifications of which I didn’t fully understand until I attended a historically Black university years later. I can only imagine how many more Black classmates I might have had in an AP course if the curriculum presented had been relatable to students of African descent.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOur contributor explores a proposed Advanced Placement African American Studies course as part of an ongoing effort to see Black history as American history. What’s behind Florida’s rejection of this latest effort?

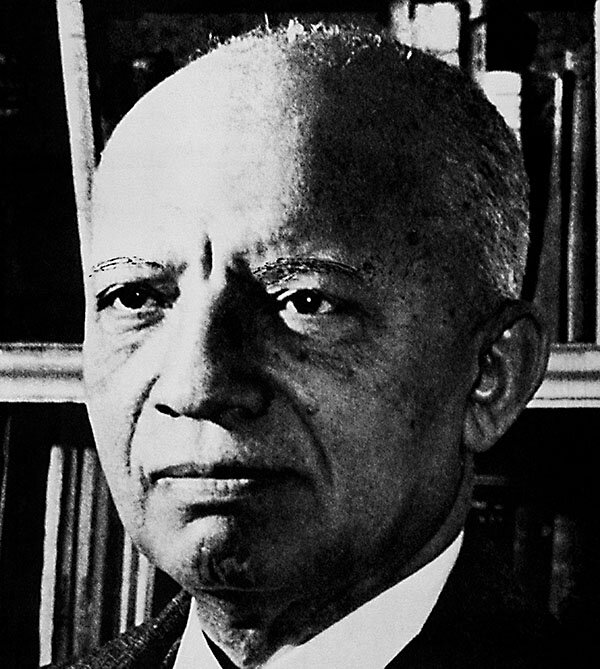

Fortunately, I didn’t solely rely on the public school system for an understanding of Black history. I still have a box of BlacFax, a Trivial Pursuit-style game that my parents bought for my younger brother and me when we were kids. I didn’t fully understand the ramifications of this either, until I became much older and gained a profound appreciation for the intricacies of Carter G. Woodson’s view of Black history.

“We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history,” he said in 1927, a year after starting Negro History Week.

Clearly, Dr. Woodson didn’t start the week, which ultimately became Black History Month, for the purpose of an annual occasion. He started it because he realized that Black people and our history had been omitted from public education.

Last week, when Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis explained his rejection of a proposed Advanced Placement African American Studies class, I thought about the small number of Black students enrolled in AP courses. A 2020 report by The Education Trust pegged it at 9%, despite counting 15% of high school students nationwide as Black.

I was one of those few Black students 20 years ago. More often than not, I was the only African American kid in my class, the social ramifications of which I didn’t fully understand until I attended a historically Black university years later. I can only imagine how many more Black classmates I might have had in an AP course if the curriculum presented had been relatable to students of African descent.

Fortunately, I didn’t solely rely on the public school system for an understanding of Black history. I still have a box of BlacFax, a Trivial Pursuit-style game that my parents bought for my younger brother and me when we were kids, with the intent of teaching us about popular African American facts along with less conventional anecdotes. I didn’t fully understand the ramifications of this either, until I became much older and gained a profound appreciation for the intricacies of Carter G. Woodson’s view of Black history.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOur contributor explores a proposed Advanced Placement African American Studies course as part of an ongoing effort to see Black history as American history. What’s behind Florida’s rejection of this latest effort?

“We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history,” he said in 1927, a year after starting Negro History Week.

Clearly, Dr. Woodson didn’t start the week, which ultimately became Black History Month, for the purpose of an annual occasion. He started it because he realized that Black people and our history had been omitted from public education.

That omission comes with a price – the devaluing of Black lives. Thought turns into deed, as Dr. Woodson expressed in “The Mis-Education of the Negro,” when he said “there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.”

Such a statement might be seen as extreme – or no longer relevant – until one looks at the reasoning behind Florida’s ban of AP African American Studies. As reported by CBS, a Jan. 12 letter from the state’s Department of Education said the course “is inexplicably contrary to Florida law and significantly lacks educational value.” Specific concerns were noted about such topics as intersectionality, reparations, Black queer theory, and “Black Study and the Black Struggle in the 21st Century.” The board also leveled criticisms at the inclusion of Black authors and activists such as Angela Davis, whom they referred to as a “self-avowed Communist and Marxist.”

Quite simply, Mr. DeSantis’ critique and the board’s evaluation contain the language of segregation. The attribution of communism as a pejorative is similar to the Red Scare rhetoric of the 1950s and 1960s, from which not even Martin Luther King was exempt.

The power of language and its importance to freedom – or oppression – cannot be overstated. It is no coincidence that Mr. DeSantis and politicians of a similar ideology choose to either attack or co-opt phrasing such as “woke” or “critical race theory.” Those phrases are seedlings, which, in fertile ground, can cultivate honest instruction and dialogue about race relations.

A commentary from one of my favorite movies, “V for Vendetta,” puts it this way in a memorable speech about revolution:

Words offer the means to meaning, and for those who will listen, the enunciation of truth. And the truth is, there is something terribly wrong with this country, isn’t there? Cruelty and injustice, intolerance and oppression.

Dr. Woodson saw Negro History Week as a steppingstone to the understanding that Black people are part of American history. Nearly a century later, some see this AP course filling a similar role.

Henry Louis Gates Jr., a noted scholar of African American history and literature, told Time magazine that the creation of the course signified “ultimate acceptance and ultimate academic legitimacy.”

“AP African American Studies is not [critical race theory]. It’s not the 1619 Project,” explained Dr. Gates, who helped develop the course. “It is a mainstream, rigorously vetted, academic approach to a vibrant field of study, one half a century old in the American academy, and much older, of course, in historically Black colleges and universities.”

But this has never been a discussion about critical race theory as much as a discussion about critical thinking. The need for Black history – American history – outside of the month of February is indisputable.

Yet “indoctrination” is the word Mr. DeSantis used to describe the course. That’s an interesting take from a governor trying to stop “woke.” I can’t help but think about another controversial governor, George Wallace, who literally attempted to block integration at the University of Alabama in 1963.

The College Board has announced it is revising the pilot course, currently taught at 60 high schools, and will announce the official framework Feb. 1. Will public school students be able to read not only about Mr. Wallace but also about the nuanced reasoning of Black thought leaders and activists, such as the Black Panthers, who embraced communism?

That’s the beauty of this controversy, though. My gut feeling is that, like Mr. Wallace, the governor of Florida will eventually have to remove himself from the doorway of history, and the taxpaying citizens of the Sunshine State, regardless of race, will then enjoy a fuller understanding of American history. At least one lawsuit, originating with high school students, is in the works if Florida doesn't reverse course.

One of the greatest lessons about education is that it doesn’t always take place in a classroom. That’s true of the study of Africans in America. Here’s hoping that the rebellious nature of people against authoritarianism manifests itself in their desire to learn more about the Negro in history.

Ken Makin is the host of the “Makin’ a Difference” podcast.