Is class conflict to blame for riots in Greece and 'Tea Party' movement?

Loading...

A presentation at this week’s NYU Colloquium by Ralph Raico, professor of history at the State University of New York Buffalo, generated a thought-provoking discussion. His paper traces the early-to-mid 19th century development of the classical liberal theory of class conflict—which long predated Marx and is different from class conflict in the Marxian sense.

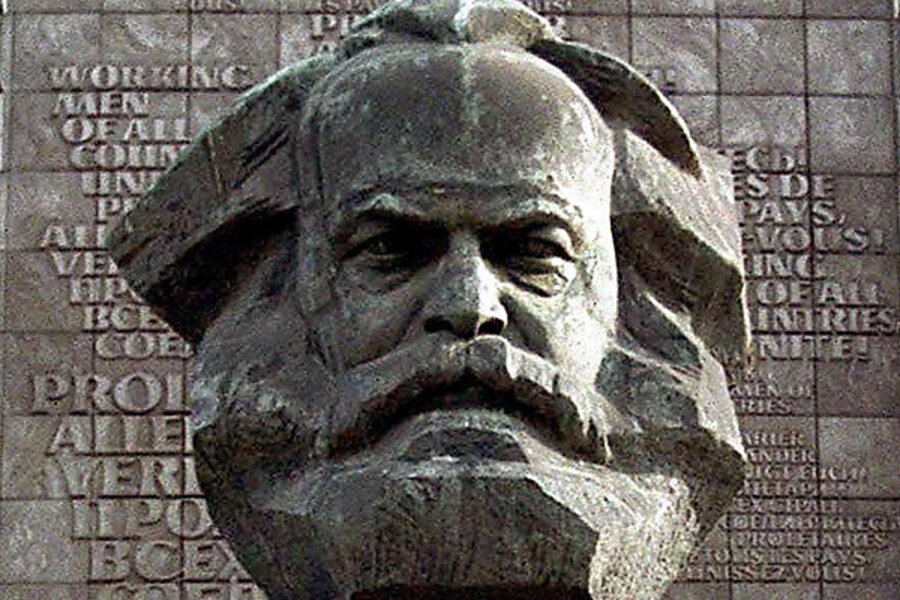

Marx and his followers identified class conflict as something that happens in the market economy, where the owners of capital appropriate value produced by workers. This market-based notion of class still dominates public discussion, with the state regarded either as a capitalist tool or possibly a mediator between capital and labor.

By contrast, from the classical liberal perspective the state and the groups that control it are the central players. Using the power to tax and regulate, the governing class appropriates society’s wealth, spends it ways to benefit itself and doles it out to political supporters. It is this old concept that makes sense of today’s economic conflicts, from riots in Greece to the rise of Tea Partiers in America.

“Class” has so many different – and overlapping – meanings that some say it is a useless term. “Class warfare” as commonly used today can describe the opposed interests of managers vs. workers, the rich vs. the poor, shareholders vs. employees or cultural distinctions like Joe six-pack vs. cosmopolitan intellectual. At the Colloquium, Israel Kirzner, professor emeritus of economics at New York University, argued that the term adds nothing.

Yet it can be a handy tool, say, to express the conflict of interest between taxpayers and public sector unions. As Adam Martin pointed out, the old notion of political class is well and alive in public choice economics. This research program explains key features of collective action such as why legislation caters to the interests of small, homogeneous groups with strong common interests at the expense of the population at large. Public choice is “politics without romance” according to James Buchanan, a founder.

Early 19th century classical liberals used vivid words like plunderers vs. producers to depict the political extraction of value—as when a lord’s armed posse “taxed” merchants. Nowadays we use more neutral terms, the system is infinitely more complicated and tax collectors are more genteel—arms come into play only when a taxpayer proves intransigent. But the central activity is the same: income is appropriated and distributed to the benefit of the politically favored.

Greek government employees recently went on strike and protested the austerity measures meant to alleviate the country’s debt problem. Whether we call them an interest group, a distributional coalition or a political class, their interests are against taxpayers who have no government sinecure. That is class conflict in the pre-Marxian sense.

Despite his all-pervasive influence on the way people thought of class in 20th century, Marx himself did not have a coherent theory and on occasion reverted back to the liberal concept. Professor Raico gives a quote that looks like it could have been written by a classical liberal but is from Marx, who described the French government as a parasite living on the rest of society: “with its enormous bureaucracy and military organization, with its ingenious state machinery …”

The old understanding of class has great explanatory power—even Marx could not completely break from it.

Add/view comments on this post.

------------------------------

The Christian Science Monitor has assembled a diverse group of the best economy-related bloggers out there. Our guest bloggers are not employed or directed by the Monitor and the views expressed are the bloggers' own, as is responsibility for the content of their blogs. To contact us about a blogger, click here. To add or view a comment on a guest blog, please go to the blogger's own site by clicking on the link above.