Stanford found guilty in $7 billion Ponzi scheme

Loading...

| Houston

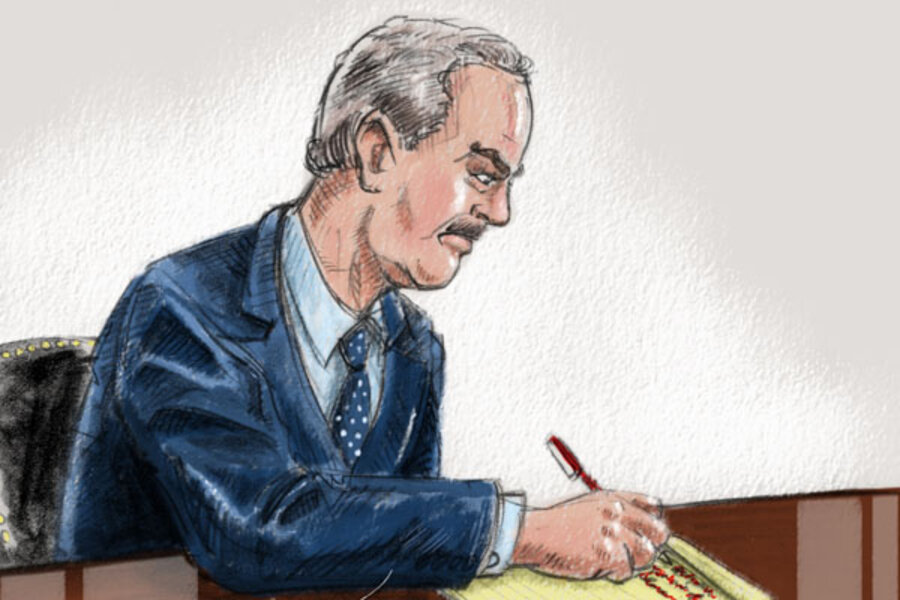

Texas tycoon R. Allen Stanford, whose financial empire once spanned the Americas, was convicted Tuesday on all but one of the 14 counts he faced for allegedly bilking investors out of more than $7 billion in massive Ponzi scheme he operated for 20 years.

Jurors reached their verdicts against Stanford during their fourth day of deliberation, finding him guilty on all charges except a single count of wire fraud.

Stanford, who was once considered one of the wealthiest people in the U.S., looked down when the verdict was read. His mother and daughters, who were in the federal courtroom in Houston, hugged one another, and one of the daughters started crying.

"We are disappointed in the outcome. We expect to appeal," Ali Fazel, one of Stanford's attorneys, said after the hearing. He said the judge's gag order on attorneys from both sides prevented him from commenting further, and prosecutors declined to comment after the hearing.

Prosecutors called Stanford a con artist who lined his pockets with investors' money to fund a string of failed businesses, pay for a lavish lifestyle that included yachts and private jets, and bribe regulators to help him hide his scheme. Stanford's attorneys told jurors the financier was a visionary entrepreneur who made money for investors and conducted legitimate business deals.

Stanford, 61, who's been jailed since his indictment in 2009, will remain incarcerated until he is sentenced.

He faces up to 20 years for the most serious charges against him, but the once high-flying businessman could spend longer than that behind bars if U.S. District Judge David Hittner orders the sentences to be served consecutively instead of concurrently.

With Stanford's conviction, a shorter, civil trial will be held with the same jury on prosecutors' efforts to seize funds from more than 30 bank accounts held by the financier or his companies around the world, including in Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Canada. The civil trial could take as little as a day.

Stanford was once considered one of the wealthiest people in the U.S. with an estimated net worth of more than $2 billion. But he had court-appointed attorneys after his assets were seized.

During the more than six-week trial, prosecutors methodically presented evidence, including testimony from ex-employees as well as emails and financial statements, they said showed Stanford orchestrated a 20-year scheme that bilked billions from investors through the sale of certificates of deposit, or CDs, from his bank on the Caribbean island nation of Antigua.

They said Stanford, whose financial empire was headquartered in Houston, lied to depositors from more than 100 countries by telling them their funds were being safely invested in stocks, bonds and other securities instead of being funneled into his businesses and personal accounts.

The prosecution's star witness — James M. Davis, the former chief financial officer for Stanford's various companies — told jurors he and Stanford worked together to falsify bank records, annual reports and other documents in order to conceal the fraud.

Stanford had wanted to testify and jurors were told he would do so, but his attorneys apparently convinced him not to take the witness stand.

Stanford's attorneys told jurors the financier was trying to consolidate his businesses to pay back investors when authorities seized his companies. Stanford's attorneys highlighted his work to build up Antigua's economy as well as his philanthropic efforts on the island. Stanford, the largest private employer on the island nation, was widely known as "Sir Allen" after being knighted by Antigua's government.

The financier's attorneys accused Davis of being behind the fraud and of lying so he could get a reduced sentence. Davis pleaded guilty to three fraud and conspiracy charges in 2009 as part of a deal he made with prosecutors.

Three other indicted former executives of Stanford's companies are to be tried in September. A former Antiguan financial regulator accused of accepting bribes from Stanford was also indicted and he awaits extradition to the U.S.

The financier's trial was delayed after he was declared incompetent in January 2011 due to an anti-anxiety drug addiction he developed in jail and he underwent treatment. He was also evaluated for any long-term effects from being injured in a September 2009 jail fight. Stanford was declared fit for trial in December.

Stanford and the former executives are also fighting a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit filed in Dallas that makes similar allegations.