Coronavirus crunch: One city block reveals small businesses at risk

Loading...

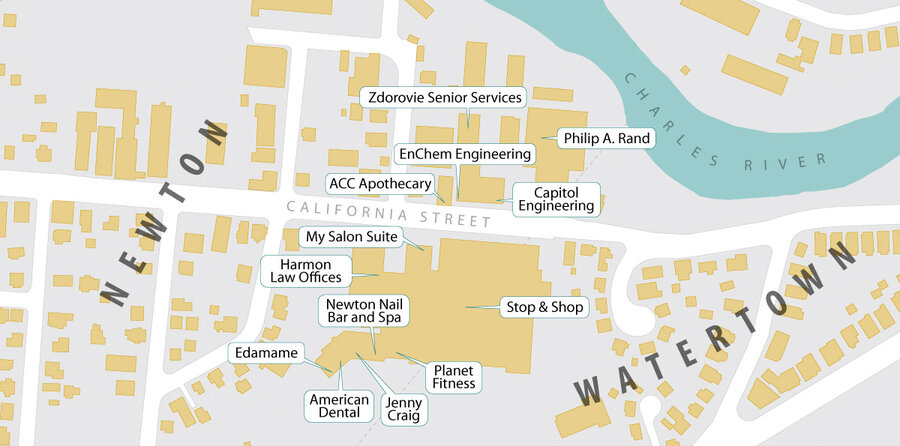

| Newton, Mass.

On one block of California Street, between the Boston suburbs of Newton and Watertown, more than 15 small businesses ply their trade in widely diverse industries but with a single problem. The state-imposed closing of nonessential companies to stop the spread of the coronavirus has severely cut into their revenue.

Philip A. Rand Wire Rope and Sling Co. is down some 70%. The dentist running American Dental and other Boston locations has seen business fall 80% or more. For small firms, it’s a race against time. Millions need to see an economic turnaround or federal aid in the next two months or so to avoid closing permanently.

Why We Wrote This

When consumers are told to stay home, the economy takes a massive hit. Our reporter visited a long-vibrant commercial street to explore the new realities that are raising doubts about small-business survival.

As shops on California Street wait to hear if they qualify for loans under Congress’ coronavirus rescue package, the importance of human connections can be paramount. One local landlord has decided not to collect rent from his business tenants this month.

“Those are the people who have been so good to us over the years,” says Werner Gossels. “We can’t do much about food and shelter, but we could say, ‘No rent. Forget this month.’”

For a man who has lost 70% of his business, Philip Rand remains remarkably upbeat.

Then again, his company, the Philip A. Rand Wire Rope and Sling Co., has proved remarkably resilient through two world wars, the Spanish flu, the Great Depression, and the Great Recession. A couple of government contracts are currently keeping its four full-time and four part-time workers employed.

“This is a new adventure; it’s a different kind of adventure,” says Mr. Rand, great-grandson of the founder, about the lockdowns that have curtailed or stopped business operations throughout the United States because of the coronavirus threat. “But we are going to survive. ... We have been around since 1911.”

Why We Wrote This

When consumers are told to stay home, the economy takes a massive hit. Our reporter visited a long-vibrant commercial street to explore the new realities that are raising doubts about small-business survival.

That’s one of the more positive outlooks along this 500-foot stretch of California Street that runs between the Boston suburbs of Watertown and Newton and houses more than 15 small businesses. They are remarkably diverse, including everything from a law office to an Asian restaurant, an air-conditioning contractor to a nail spa. And with the exception of the Stop & Shop grocery store, which is bustling, and maybe one or two others, all of them have been hit by the state’s stay-at-home advisory and orders for “non-essential” businesses to close.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Small businesses are bone and sinew to the U.S. economy. They represent 99% of all firms and employ about half of all working Americans. More than 40% of the nation’s economic activity flows through their ledgers. While any firm with less than 500 workers can be considered “small,” nearly 9 in 10 of these firms have fewer than 20 employees. And with far fewer resources than big corporations, they’re also the most vulnerable to a downturn.

Already last month, when an employment report by payroll firm ADP showed midsize and large companies still adding employees, firms with fewer than 50 employees laid off a combined 90,000 workers. “Small companies got hammered,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics.

And they’re racing against the clock. The longer the lockdowns persist, the more likely they are to close permanently. A survey last week by the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) found that about half of small firms say they can survive for two months at the most.

The small businesses along California Street reflect the squeeze and the concern, but they also tell a richer story about how money flows and sometimes doesn’t, the fragile interdependence of local business, and the importance of human connections, even in an era of social distancing.

Some stores have been spared closure because they are essential businesses, like grocery stores. Planet Fitness, a workout gym, has shut its doors. But the Jenny Craig weight loss clinic two doors down is still open because it sells food. Still, staying open is no guarantee of profit.

“Open” but in trouble

While the Jenny Craig store offers curbside service for limited hours and is seeing “a steady flow of clients,” according to Faith Hanson, marketing director of the north Boston area for the Jenny Craig corporation, American Dental next door is effectively closed, used only for emergency root canals.

“Everybody’s been affected,” says Dr. Z. Bender, part of the management that operates this location and four others in the Boston area. Three of them are still open, but like many dentists in Massachusetts, Dr. Bender is only handling emergency situations and treatments that require immediate attention. He’s had to lay off roughly half of his 40 employees, while providing bonuses and protective equipment, including face shields, to those still working.

Revenues are down 80% or more, he estimates. So he’s looking to get referrals from other locations and do some promotion to boost business, because the current situation is not sustainable, he says. “If we are going to keep operating this way, we would be able to continue for a few weeks.”

It’s a situation faced by many small businesses. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, among the healthiest firms only 1 in 5 said they had the cash reserves to continue business as usual if revenue dried up for two months, according to a new survey of small business credit by the regional Federal Reserve banks. For all other firms, the figure was less than 1 in 10.

Will aid come in time?

For these reasons, Congress has rushed aid to small businesses. A week ago, firms began applying for $350 billion in forgivable small business loans, part of the $2 trillion coronavirus rescue package. Many of the businesses along California Street – as well as some 70% nationally, according to the NFIB – have already applied.

For some, it’s not clear if the help will come in time. The owner of the Newton Nail Bar & Spa vows in an email to serve customers again soon. But after launching last year, the shop’s phone number no longer accepts calls and, aside from a “Grand Opening” banner still hanging in its window, there’s no sign telling clients the now-darkened store will reopen.

“I got a manicure a week before all this happened,” says Debbie Fredberg, co-owner with her husband of the My Salon Suite just up the street. “They put a lot of money into it. You can tell. At the time, they seemed upbeat.”

This is one of the lessons of California Street: In business, timing can be everything. While Newton Nail Bar & Spa opened at the wrong time, Ms. Fredberg’s salon may get some breathing room from being still in the preparation phase. “Coming Soon” posters adorn its windows. Due to open this month, the site is now on hiatus; construction stopped just as workers were beginning to move in the furniture.

“It’s a disappointment,” she says, but hardly a big blow. Unlike a regular hair salon, the franchise rents out fully equipped individual rooms to stylists as well as massage therapists and beauticians. Getting one’s hair styled in a private room may be popular in a post-pandemic world, she adds. Some 80% of the salon rooms are already spoken for.

The economy as an organic web

Another lesson of California Street is that local business owners and workers tend to patronize each other, popping into the Stop & Shop for groceries, or eating at Edamame, the Asian restaurant behind it. Edamame tried to stay open offering takeout and delivery, stocking an outdoor rack of menus that got wet from the rain. But by Wednesday of this week, a note was taped to the door saying the restaurant was temporarily closed. Its customers’ money, presumably, will flow down the block to Stop & Shop, or to other supermarkets.

In a normal year, Americans spend more on food eating out than they do at home. But the lockdowns in the past month have meant a huge diversion of spending from restaurants to grocery stores. The National Restaurant Association estimates the total at some $25 billion since March 1, which has put 3 million people out of work. It figures 15% of restaurants will close permanently within two weeks, if they haven’t already done so.

Other money has stopped flowing at all, and that has a ripple effect. Closed offices mean the cleaning businesses have fewer to clean. Van drivers for the senior center and air-conditioning specialists are now laid off, which means they sit at home and spend less.

Some small businesses appear to be doing just fine. “We are busy and we are also running shorthanded,” writes Arthur Margolis, president of ACC Apothecary, which specializes in custom-made prescriptions for patients. “All I can say is that we are open and we have patients in 8 states that we are taking care of.”

Nationally, 3% of small businesses surveyed by the NFIB were positively affected by the virus. But 92% were adversely affected, even if business owners are hesitant to talk about it.

“Clients are holding on to their money,” says the owner of EnChem Engineering, a remediation specialist for hazardous-waste sites, who doesn’t give his name or take off his face mask. But “we are able to keep going.”

Connections in a “distanced” world

The other aspect of business here on California Street is how personal it is. For all the moves to physically distance people, they still make social connections. It’s the essence of business, exchange among individuals.

Behind EnChem Engineering, Zdorovie Senior Services is closed down. All the employees have been laid off. Even if it was open, it’s unlikely that retirement homes would let their clients travel and congregate. “But I regularly call them to check up,” says a manager, who won’t give her name.

This month, EnChem and the other small-business tenants in the building received an unexpected surprise. The landlord was not collecting rent for April.

“The tenants are the same general type,” says Werner Gossels, who owns the building and others in several communities around Boston. “It’s a family business with one or two or three people.”

It was a decision that cost Mr. Gossels hundreds of thousands of dollars. But “those are the people who have been so good to us over the years,” he says. Now, there’s “the fear that everybody has – suddenly they have no business, they have no knowledge of where they’re going. We can’t do much about food and shelter, but we could say, ‘No rent. Forget this month.’”

“It looks like we may have to do May as well,” he adds.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.