Why retailers are moving away from ‘on-call’ shift scheduling

Loading...

For more than two decades, workers in the retail and restaurant industries have struggled to balance family life and other obligations with jobs that demand they be “on call.” Now, under legal pressure and in a tightening labor market, some employers are changing their approach.

On Tuesday, the New York Attorney General’s office announced that six retailers – Aeropostale, Carter’s, David’s Tea, Disney, PacSun, and Zumiez – have agreed to end “on-call” scheduling. From now on, their employees will not need to check each day whether they should come to work, nor do they risk being sent home early without pay when the store is quiet. Four of the companies also committed to giving employees their schedules one week in advance.

Ending “on-call” scheduling will make a big difference for employees, increasing the predictability of work schedules and making it easier to plan other activities. But they aren’t the only ones who will benefit from the change, observers say: It could also bring long-term benefits for businesses and society.

“It’s a pretty significant move,” Carrie Gleason, director of the Fair Workweek Initiative at the Center for Popular Democracy, tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview. “Retail companies ... are really starting to recognize that they need to invest in their workforce.”

In the past, workers’ wages were considered a fixed cost, wrote Robert Reich, who served as Labor secretary during Bill Clinton’s presidency and is now a professor of public policy at the University of California at Berkeley. In the 1990s, however, wages became a variable cost: Many businesses used on-call scheduling to trim costs by having as few workers as possible. Some even deployed software systems that highlighted the times when employees were least needed.

That kind of scheduling takes a substantial toll on workers, explains Lonnie Golden, a professor of economics and labor-employment relations at Penn State University-Abington, in a phone interview with the Monitor. Professor Golden was the primary author of an April report for the Economic Policy Institute about the consequences of irregular work scheduling.

Uncertain hours make it hard for workers to plan their daily lives, says Golden. Holding down a second job becomes more difficult, uncertain paychecks mean incomes often fall short, and childcare is an increased challenge.

These employees are most likely to experience “work-life conflict” and be stressed at work, Golden notes.

That also puts businesses with “on-call” scheduling on the wrong side of some state and federal labor laws. In April, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and the attorneys general of seven other states and the District of Columbia sent a letter to the six retailers asking them to end the practice, as they have now agreed to do.

Ms. Gleason points to that April letter and other, similar investigations as the "single most influential factor" in moving businesses away from these scheduling practices. Seven other businesses announced that they would end "on-call" scheduling in 2015.

But with a new presidential administration kicking off in a few weeks, the future of these investigations is uncertain.

“The incoming Labor Secretary is [at] the complete opposite end of the spectrum,” Gleason says, making it “incumbent now on states” to continue pushing for these standards.

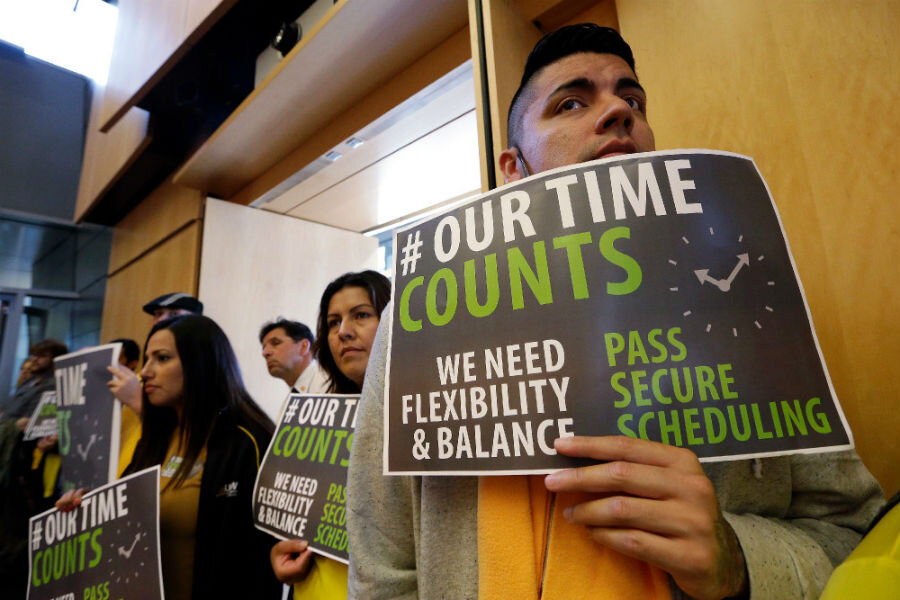

Worker-friendly policies are becoming bipartisan causes in many states, the Monitor’s Schuyler Velasco wrote in October – and New York is one of several states working toward a legislative ban on “on-call” scheduling. In September, Seattle's city council unanimously passed a “secure scheduling” law, which requires employers to schedule their workers 14 days in advance, and includes a "right to rest" provision that allows workers to decline closing and opening shifts that are less than 10 hours apart.

Businesses themselves may have incentives to end on-call scheduling. In a tightening labor market, employers want to hang on to their workers, notes Golden, who is also a senior research analyst at the Project for Middle Class Renewal at the University of Illinois. And businesses that offer better hours – and more consistent hours – are more appealing to workers, leading to better retention.

The more businesses sign on to these measures, the more workers’ wages are taken out of the cost-cutting equation. More than 300,000 workers have been impacted so far, says Gleason.

Greater certainty about schedules has benefits beyond individual workers, she says. If people know when they’re working, they can also schedule time to be with their children, or attend college and grad school classes.

“Employees are going to be better off, and maybe even society,” she says.