The real story behind Trump's Pershing tweet: how General Pershing handled Muslim insurgents

Loading...

Donald Trump likes to tell the story of how a famous American military leader vanquished terrorists with some horrific terrorism of his own. Supposedly – and falsely – General John J. "Black Jack" Pershing ordered the slaughter of 49 Muslim insurgents with bullets dipped in pig's blood and told a sole survivor to go home and warn his counterparts. "There was no more Radical Islamic Terror for 35 years!" President Trump recently tweeted.

He's apparently referring to the Moro War and Pershing's service in the southern islands of the Philippines at the beginning of the 20th century. Pershing, later commander of American troops in World War I, managed American's efforts to gain control of the Moro society, dominated by a warrior culture devoted to Islam.

It's not just Trump's tall tale about the killing of 49 insurgents that misses the mark, a leading historian of the conflict says.

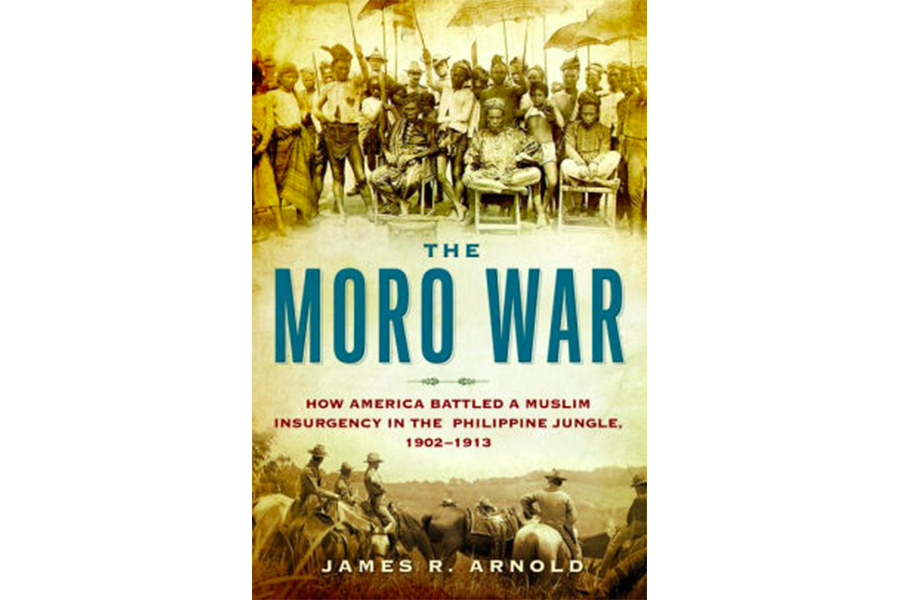

"The Americans were not simply ruthless and brutal," says James R. Arnold, author of 2011's The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. In fact, while Pershing was tough, he also embraced a gentler American approach that focused on hearts and minds, Arnold says.

In modern times, Islamic terrorism is believed to be growing in the southern Philippines. But a century ago, Arnold says, Pershing's strategy helped produce decades of peace.

Q: How did the US end up in charge of a province in the Philippines?

It started with the Spanish-American War. We received the surrender of the Spanish in Manila, and by default, we acquired "Moroland," which includes the island of Mindanao and was part of the Spanish empire.

Q: Who were the Moro people?

Their society was divided into a hierarchy with the people called the Datus at the top, then a privileged class of free citizens at the next level. At the bottom were slaves.

Islamic preachers had come there in the 1300s or 1400s, and the Moros adopted Islam. All Moro laws were Sharia law, and they thought of their land as the household of Islam. There was no separation of church and state or sacred and secular, and Islam pervaded everything they did.

America looked at them as a bigamist, slave-holding society, as savages. We were going to introduce Western civilization to them.

Q: What led them to fight back against the Americans?

They were a warrior culture. They called themselves the People, and their sense of ethnic unity provided an enduring bond. They fought the Spanish when they first came, and then they fought the Americans.

Q: What made them unique as fighters?

They used suicide warriors to break into American camps to "run amok," slash, and kill as many men as they could before they were killed. Pershing periodically lamented the fact that the Moro never seemed to learn from experience: We fight them in battles, we kill them in incredible numbers, and then they'll do it again in a year or two.

Q: What does Trump get wrong about Pershing?

Pershing had a carrot-and-stick approach. He tried to implement economic development, and once he left, the next fellow did that, too. We acted as engineers, we improved the waterfront, put in water systems, roads, hospitals, schools.

Q: What eventually ended this war?

Pershing went back for a second tour of duty. He was so frustrated by the ongoing war that he decided the only way to go forward was to disarm the Moro, who openly wear these small, dagger-like swords.

They won't surrender them or the handful of firearms they have. So essentially, we beat anyone who resists us in a field battle. We have machine guns, and they have spears and a few muskets.

We kill a bunch of them, and by 1913, there's no organized resistance.

Q: Did the terrorism actually stop for decades?

Yes. What worked was that Pershing sought to replace military officials with experienced American civilians as soon as the violence was officially tamped down.

We had people some who liked and understood the Moros and realized you had to sit and talk with them for hours. There were a handful who were able to do it, and they developed good relationships with them. That probably led to the long period of peace that lasted until World War II.

Q: What do you think we can learn from this war when we again face this kind of situation?

If we can try to understand but not change culture, perhaps we can be seen as a path to a better future.