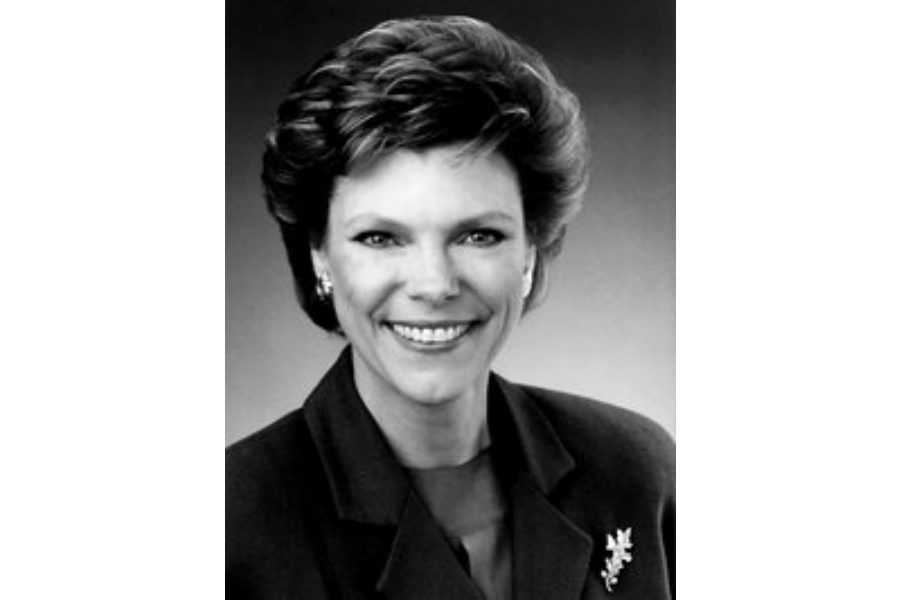

Cokie Roberts highlights the Civil War-era women who held the nation together

Loading...

People even casually interested in the Civil War can list the major players: President Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and William T. Sherman. Maybe throw in Frederick Douglass and Jeb Stuart, too.

Notice anything strange about those names? All men and all white, with the exception of Douglass. While the women’s liberation movement in the 1960s raised the issue of gender equity in academics and the telling of history, broader mainstream awareness remains paltry when it comes to what half of the population was up to during important moments of the past.

Cokie Roberts, the NPR and ABC News political analyst, is helping to reverse such cultural ignorance in American history. In 2004, she wrote “Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation,” using letters, journals and other documents to tell the story of early-US history with perspective from and about important figures including Martha Washington, Eliza Pinckney, and Deborah Read Franklin, women who all had a unique vantage point during the Revolutionary era.

Then, in 2008, came “Ladies of Liberty: The Women Who Shaped Our Nation,” examining the achievements and sorrows of notables such as Sacagawea, Theodosia Burr, Martha Jefferson and Dolley Madison, among others.

Roberts again combines her historical interest and long personal knowledge of Washington politics in her new book, Capital Dames (494 pp., HarperCollins). Her latest history, published to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, follows the lives of wives, sisters and daughters of influential politicians as well as remarkable activists.

The latter category includes Elizabeth Keckley, a freed slave who became a successful dressmaker after impressing influential customers such as Varina Davis, wife of then-US Senator Jefferson Davis, who soon afterwards became the president of the Confederacy.

First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln hired Keckley in 1861 for a job that, in today’s terms, might be described as a combination of personal stylist and personal assistant. She became Mrs. Lincoln’s confidante and, several years after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, published a highly publicized and scrutinized account of her White House years.

Roberts details the ups and downs of Mary Todd’s volatile tenure as First Lady (her excessive shopping debts, her lack of acceptance in Washington society, and her persistent anxieties) while also bringing to life Keckley’s journey from slave to entrepreneur to founder of a relief agency dedicated to helping the poverty-stricken freed slaves. Then, too, there is the rivalry between Mary Todd Lincoln and Kate Chase. Both Lincolns faced the scorn and plotting of Chase, the attractive, popular and bratty daughter of Lincoln’s treasury secretary, Salmon Chase.

During a recent interview with The Monitor, Roberts told me her publisher encouraged her to consider a Civil War book. At first, she hedged before committing to the project.

The daughter of prominent Louisianans, Roberts joked about her initial reluctance, saying, “All of my ancestors fought on the losing side.”

Her father, Hale Boggs, was a 14-term Democratic Congressman from New Orleans and, when he died in a plane crash in 1972, was also the House majority leader. Roberts’s mother, Lindy Boggs, successfully ran for her husband’s seat in Congress and held the district for nine terms before retiring in 1991.

Roberts has been surrounded by politics all of her life. What made the Civil War book resonate for her was thinking about her childhood.

“I nibbled around with a few ideas,” she said. “Some things didn’t pan out. Facts getting in the way of a good story – it happens all the time. But I started thinking about when I was growing up in Washington during World War II and how present [the war] was. It just changed the pace of the city, literally. I knew Rosie the Riveter [the iconic symbol of women working in factories to produce weapons and products while the men went to war] and I started wondering whether the Civil War had the same impact and it did.”

Roberts said that hook led to the “pure fun” of researching life in Washington.

In “Capital Dames,” Roberts explores those dramatic changes. She notes the federal budget nearly quintupled, to $377 million, from 1860 to 1867. During the four-year war, the city’s “population almost doubled.”

In almost every way, war overwhelmed Washington. The 555-foot Washington Monument, a marble obelisk that, for many, still symbolizes the nation’s capital, stood unfinished and unfunded throughout the Civil War, stuck at 135 feet. The expenses of war kept the monument from being completed until 1884.

And, in a situation that strains credulity as a visual metaphor, the US Capitol stood incomplete for 11 years while the domed roof was built.

The women Roberts writes about lived in near-constant hardship. She illustrates how the Congressional wives and daughters went from a society of belles and balls to seeing their husbands, sons, and brothers injured and killed by war.

Even the Southern losses caused heartache to the Union women who stayed in Washington. The reason: Many of the Confederate dead and wounded were the sons, husbands and brothers of the Congressional wives from the Southern states, women who had been friends and neighbors with their Northern counterparts before secession forced them apart.

Many of the insights come from previously unpublished letters, diaries and other documents. Roberts, working with historical societies she befriended while researching her Revolutionary-era books, delighted in reading the unvarnished truth from the pens of hostesses such as Elizabeth Blair Lee (daughter of Francis Preston Blair, the founder of the Republican Party, and sister of Montgomery Blair, a member of Lincoln’s cabinet), Abigail Brooks Adams, Virginia Clay, and Adele Cutts Douglas. Each of these women, and others Roberts writes about, exerted influence on their husbands and other leaders while pushing for improvements to the city as a whole.

“Their letters were so much better than the men’s,” Roberts told me. “The men were very self-important.”

Among the gems: Varina Davis, then a senator’s wife, shares her disgust over the marriage of presidential aspirant Stephen Douglas to a woman half his age, 21-year-old Adele Cutts.

Roberts writes that Davis “added snarkily that a new water system would soon be coming to Washington, so ‘sparing his wife’s olfactories Douglas may wash a little oftener.’” As the direct quote makes clear, Mrs. Davis thought Douglas stank in every way.

In 1860, Abigail Brooks Adams, wife of Massachusetts Congressman Charles Francis Adams (son and grandson of Presidents John Quincy Adams and John Adams), made an astute observation of the upper chamber suitable for use in 2015. Members of the Senate, she noted, “behave like children and silly ones at that.”

More serious stories surface, too. Harriet Lane, niece of President James Buchanan, blended fashion sensibilities and philanthropic causes to such effect that she became the first woman dubbed the First Lady in the White House.

Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix defied convention and established health campaigns and organizations that remain relevant to this day. Barton’s battlefield heroics, despite initial disdain and rejection by some military men, included working three days without sleep to aid the maimed and dying at Antietam. Throughout the war, Barton solicited food and bandages for soldiers and sought to impose better standards of care. She went on to found the American Red Cross after the war. Dix, who oversaw nurses during the war years and spent the immediate aftermath “securing pensions for the wounded,” later became a tireless advocate for mental health.

Roberts tells the story of Rose Greenhow, a Confederate spy living in Washington, with particular relish. She notes Greenhow “had been largely responsible for the Rebel victory at Bull Run” by gleaning “the date of the Yankees’ advance” and relaying it to Confederate commanders. Greenhow, whose niece was Adele Cutts Douglas, knew many members of Congress and socialized with them and other Union leaders, taking careful mental notes and sharing her intelligence with the South.

Even after detective Allan Pinkerton determined Greenhow was a spy and had her placed under house arrest, “Rose kept finding ways to receive and reveal important information,” Roberts writes. Greenhow was freed and later drowned, becoming a minor Southern martyr.

Lincoln’s assassination led to many things, including the execution of the first woman in American history. Mary Surratt, branded a co-conspirator, was found guilty by a military court and hanged in July 1865. Surratt owned a boardinghouse where her son, John Jr., met with John Wilkes Booth and other pro-Confederacy plotters who vowed to kill Lincoln and others in his administration.

After delving into the Revolutionary and Civil War eras, Roberts would seem to be the perfect candidate to shine a spotlight on Washington women during the 20th century wars and beyond.

She offers two answers. Upon being asked about another history project, Roberts compares such an inquiry to asking the mother of twins about having more children two months after giving birth. And as for the modern era? “I like the 19th century,” she said. “I’ll stay back there.”