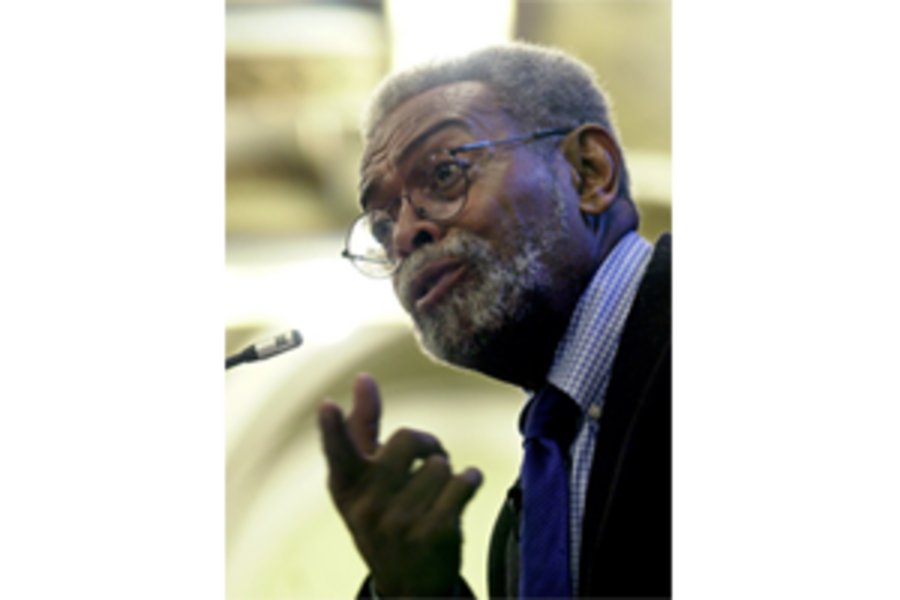

Poet Amiri Baraka, founder of the Black Arts movement, dies at 79

Loading...

Poet Everett LeRoi Jones, known as Amiri Baraka, died on Thursday, Jan. 9, in Newark. Baraka had been hospitalized at Newark's Beth Israel Medical Center since Dec. 21. His death was attributed to "failing health." Baraka was 79.

A political activist, poet, playwright, and critic, Amiri Baraka was one of the most important and controversial African American literary voices. "Amiri Baraka believed poetry to be a process of discovery of one's inner feelings," his website says. "Like the projectivist poets, he has always been of the opinion that the poetic writings should follow the shape of writer's own breath. During the African-American Civil Rights Movement, Baraka's politically charged essays and writings proved to be extremely influential for the local audiences."

His experience growing up in Newark and its milieu were very complex, and he believed that his feelings of resentment about racial prejudice fueled his writing. He often tried to shed light on the black experience by sharing personal anecdotes, such as the time he was denied admission into a segregated library as a child. His influences ranged from Allen Ginsberg and Ray Bradbury to Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Baraka was friends with Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, and was a writer associated with the Beat Generation in the 1960s. After Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965, he decided to live by more radical ideals. He then helped found the Black Arts Movement that started in Harlem in the same year.

He wrote in his 1965 nationalist poem, “Black Art,” a manifesto for the movement: “[...] we want ‘poems that kill.’ /Assassin poems, Poems that shoot /guns. Poems that wrestle cops into alleys /and take their weapons leaving them dead /with tongues pulled out and sent to Ireland.”

In 2002, Baraka’s writing sparked controversy for allegedly implying in his poem “Somebody Blew Up America” that Israeli workers at the World Trade Center had advance knowledge of the 9/11 attacks. Critics were quick to accuse him of antisemitism, which he denied. "The recent dishonest, consciously distorted, and insulting non-interpretation of my poem by the Anti-Defamation League is fundamentally an attempt to defame me and, with that, an attempt to repress and stigmatize independent thinkers everywhere," Baraka said. He was the New Jersey’s poet laureate at that time, and the controversies over the poem caused the state to remove his position in 2003.

Baraka also wrote several books about the history of black music, including the 1963 seminal study "Blues People: The Negro Experience in White America and the Music That Developed from It," which influenced ideas about the significance of African American culture.

"I think the ‘Blues People: The Negro Experience in White America and the Music That Developed from It’ might be his signature work. And that introduced jazz studies to the American academy," historian and author Komozi Woodard told NPR.

While some critics have criticized Baraka’s writing as homophobic, antisemitic, ad hominem, and even misogynist, others say his highly political and incendiary works have great literary merit. Recently, critic Arnold Rampersad named Baraka as one of the most historically significant African American literary figures, next to Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Frederick Douglass, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Baraka taught at both Yale University and George Washington University, and was a professor emeritus at Stony Brook University of New York. His recognitions included awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Guggenheim Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, and PEN/Faulkner Foundation.