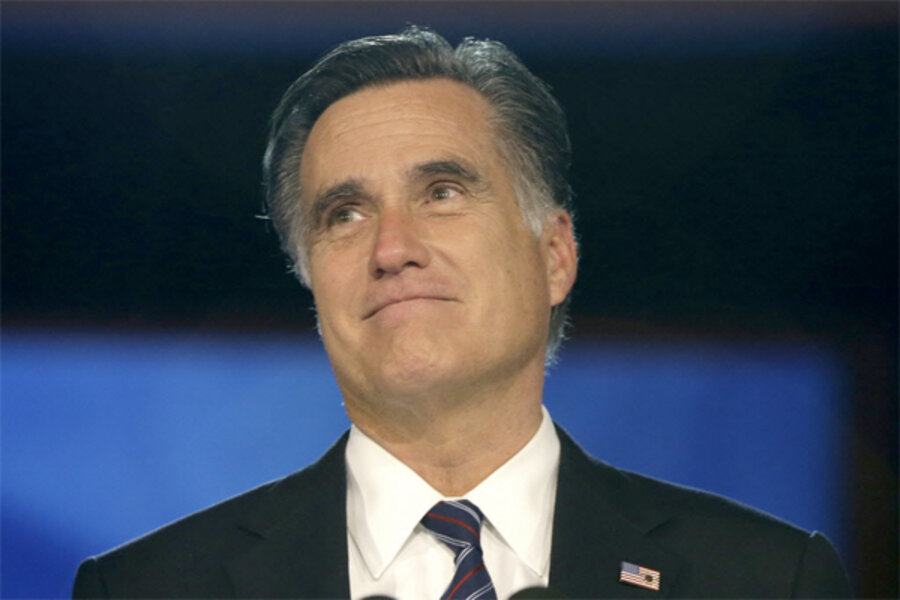

Romney's loss: How he compares to other presidential also-rans

Loading...

My spell-checker doesn't like losers.

It recognizes presidential last names, even Fillmore, Van Buren, and Coolidge. But it's dumbfounded by McCain and McGovern, let alone Willkie, Frémont, and Breckinridge.

Such is the fate of most of the major candidates who make it onto presidential ballots, but no further. Some are forever forgotten (Thomas Pinckney, anyone?). But others manage to make a mark despite coming up short.

Where will Mitt Romney fit in? For perspective, I contacted author Scott Farris, a leading specialist in presidential also-rans who wrote 2011's "Almost President: The Men Who Lost the Race but Changed the Nation."

Farris has some experience with the phenomenon of non-winning: he's run campaigns, been a political columnist, and even ran for Congress in Wyoming in 1998. (He lost.)

From his home in Portland, Ore., Farris considered Romney's options, pondered the fates of the second-placers, and looked back at a sore loser or two.

Q: What's next for Romney?

A: He's made it clear – or at least his wife has – that this is his last campaign. That eliminates the option of the loser making one more run at the presidency, which doesn't happen as often as it used to.

I look at him and think about Bob Dole in 1996. The day after the election, he held a press conference and said that, for the first time in 50 years, "I don't know what I'm going to do today."

That's a bit where Mitt Romney is.

Dole wrote a couple of books, he did some advertising – some of it notorious, like for Viagra and a controversial spot for Pepsi. He made a lot of speeches and ended up reconnecting with George McGovern to work to combat world hunger.

They ended up saving hundreds of thousands of children. It's been a very admirable career.

My guess is that Romney will do a hodgepodge of things. Could he be one of his church's leaders and continue to try to gain acceptance of the Mormon faith? He also obviously has a big family and will spend a lot of time with them.

I'm sure it will take some time for him to find himself.

Q: Who are some losers who set a high standards?

A: For the first 150 years of the US, it was OK to be a loser, you weren't stigmatized. Henry Clay lost but remained very influential. And William Jennings Bryan was an extremely influential man for a quarter century.

There are so many ways to serve.

John Kerry and John McCain went back to the Senate. Michael Dukakis completed his term as governor of Massachusetts and decided to become a college professor. Some of his students still talk about what a terrific teacher he is.

Q: Who should not be emulated?

A: Horace Greeley, who ran against President Grant, died within a month of the election, which he lost badly. He'd just lost his wife, and when he went back home, he realized he'd lost his beloved newspaper, too.

He had the most tragic life of a losing candidate.

Q: Who did the most to help his rival after the campaign?

A: Stephen Douglas worked very hard to work with Abraham Lincoln and convince the South to not secede.

The assumption is that Lincoln is a secular saint, and Douglas, his rival, must have been representing the dark side. There's no doubt he was a racist and on the wrong side of slavery.

But when the chips were down, he made a heroic effort. When he realized that he had no chance to be elected president, he devoted all his energies to trying to preserve the union and he spoke highly of Abraham Lincoln.

The only one you could compare that to is Wendell Willkie, who ran against Franklin Roosevelt.

FDR asked for his help to sell "lend-lease" to the American public, to lend weapons, ships, and tanks to the British before the US got into World War II.

There was a huge sentiment to not enter the war, but it passed with a narrow margin. An alliance between the two also helped get Congress to extend the draft six months before Pearl Harbor.

Q: What about bad behavior? Were any also-rans less than gracious?

A: The two most ungracious of modern times were Barry Goldwater and McGovern. They really disliked the men they lost to.

Goldwater was appalled by some of Lyndon Johnson's tactics. Even though it was clear he was losing on Election Night, he didn't concede until the next morning and gave a fairly defiant speech.

When McGovern conceded, he said there was no way we're going to rally behind policies we abhor. When Inauguration Day came, he refused to show up and went abroad to criticize Nixon's behavior on foreign soil that day.

That would generally be considered bad form.

Q: Who's the most obscure also-ran of all?

A: That's probably Alton Parker, who ran against Teddy Roosevelt.

He was of the old "front porch campaign" school, while Roosevelt was very energetic and toured the country.

Parker is the only losing candidate who's never had a biography published. That's pretty obscure when you're up against candidates like Lewis Cass and Winfield Scott Hancock.

Q: Ahem.

A: I'm afraid he's not driving me to write one. I've got a few book in mind, but he's not in the hopper. Maybe someday!

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.