Election season: Remembering the strange election of 1876

Loading...

Let's put it this way: you can't take me anywhere.

About 13 years ago, I visited the Jimmy Carter Library and Museum in Atlanta with some friends. For some reason, I decided it would be fun to pose for a photo in the chair behind the desk in the mock Oval Office.

First I tripped over the velvet museum rope. Then the desk chair swung backwards as I sat in it, nearly flipping me over. Finally, I held up the desk's "The Buck Stops Here" sign for the photo and watched helplessly as its little metal holder fell off and clattered onto the floor.

That's when the security guard arrived on the scene. "Step away from the desk, sir."

I did as ordered. But we weren't evicted and even got to continue our tour.

Since then, I've joked that while they're pretty lenient at the Carter museum, folks are even more easygoing at the museum of the mostly forgotten Rutherford B. Hayes. There, you can stay the night in his bed and go home with a piece of his living room couch!

That's not true. (I checked, just in case I ever find myself in Fremont, Ohio.) But Hayes is definitely one of our most obscure presidents. It's a funny thing, since he landed in office thanks to one of the most remarkable – and crooked – presidential elections in American history.

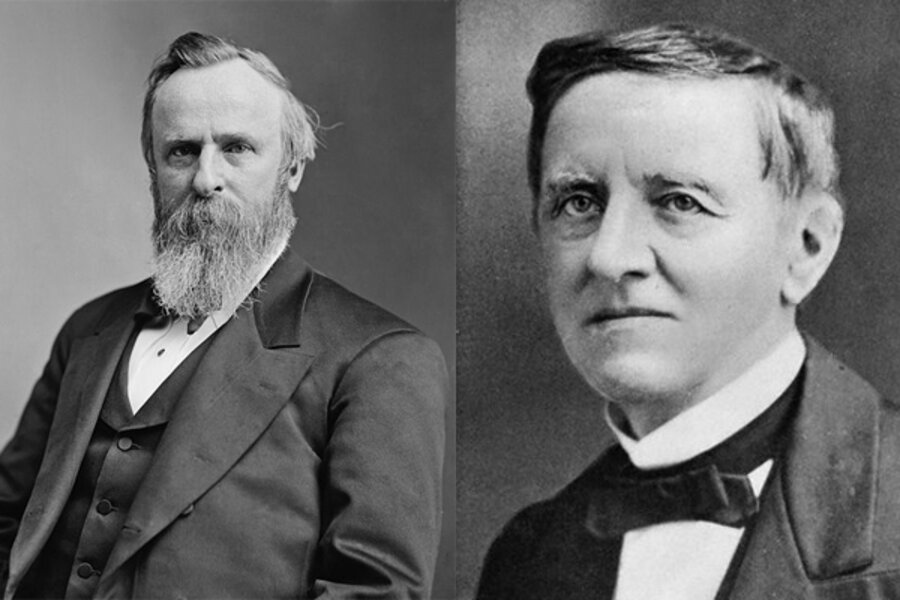

As pundits dream of a tie in the Electoral College this year, I contacted historian Roy Morris Jr., editor of Military Heritage magazine and author of 2005's "Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876."

From his home in Chattanooga, Tenn., Morris talked about the bitter battle over the disputed results, the chicanery that cast the entire election in doubt and the shrewd tactics that turned Hayes into a winner.

Q: Set the scene for us. What happened during the presidential election of 1876?

A: The Democratic nominee was Samuel Tilden, governor of New York, and the Republican nominee was Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio.

The country had just lived through eight years of the Grant administration and all its scandals. Tilden got the nomination because he was a squeaky clean reformer and had run the fight against Boss Tweed corruption in New York. Hayes got the nomination as a kind of compromise.

On election night, both candidates went to bed thinking Tilden had been elected because he had massive majorities of votes.

He was ahead by the modern equivalent of 1.3 million votes. In terms of the Electoral College, he needed 185 and he had 184 definitely.

Q: That's when an infamous character named Daniel Sickles entered the picture, right?

A: He'd been a Union general and a congressman and was notorious because he shot and killed an unarmed man who was having an affair with his wife, Francis Scott Key's nephew. Sickles was acquitted in the first acquittal based on a temporary insanity defense.

On election night, he was going to back to his house on Fifth Avenue in New York City and dropped by the Republican national headquarters a few blocks away to see what was going on.

There was only one person there, a clerk who was boxing up the office. He said, "Tilden's been elected."

But Sickle knew that Florida, South Carolina and Louisiana still had Reconstruction governments. They had 19 electoral votes, and both Republicans and Democrats had sent telegrams wondering who'd won those states.

Sickles figured out that if Hayes was declared victor in one of those states, he'd win by one electoral vote. He sent out telegrams to governors of those states and said, hold onto your states for Hayes, and if you do, he's elected.

Q: But you can't do that. You can't tell a governor to hold a state, right?

A: But he did.

Enough doubt was created in people's minds – sort of like with Bush and Gore in 2000 – that nobody knew exactly who had won. The first stories started coming out, and the Republican newspapers including the New York Times, said the election was undecided and Hayes claims victory.

Q: So the Republicans started controlling the narrative?

A: That's exactly right.

Q: How long did the stalemate last?

A: You went through several weeks of nobody knowing who had won.

Congress would meet in January and open the returns. The problem was that in those three Southern states, there were multiple sets of election results, one sent by the Republican governor and one by the Democratic governor-to-be.

To make it even more complicated, the Constitution at the same time said the president of the Senate would open the ballots.

The Republicans said that means he can decide which returns to accept, but the Democrats said he only can open them if there aren't two sets of results. If there are, he'd have to set them both aside, in which case nobody would have the majority of votes and it would then be turned over to the House to decide who'd be president.

Q: What happened next?

A: An election commission voted 8-7 that Hayes had been elected. He was sworn in secretly a day earlier than the scheduled inauguration because they were afraid that Tilden would go to Washington D.C. and declare himself president.

Q: This all happened just 11 years after the Civil War. How tense did things get?

A: A lot of the Democrats were saying that they would just march on Washington and seat Tilden. The slogan was "Tilden or blood."

Then there were secret meetings between Hayes supporters and Southern Democrats. The Democrats said that if he would end Reconstruction in these three states, they wouldn't prevent him from being inaugurated. They wanted control of their state governments more than they wanted a Northern liberal being elected president.

Q: What did Tilden, the Democratic candidate, do?

A: It was very similar to Bush vs. Gore. The Democrat was much more of a hands-off kind of guy in the interim, and the Republicans were much more active about making sure they claimed the election.

One reason Tilden lost was that he was a lawyer and assumed that if they followed the letter of the law, he'd be elected.

The Republicans in both 1876 and 2000 were much more active in pressing their case and controlling the narrative beforehand by claiming that they'd won in the first place. Gore, in 2000, and Tilden took a more admirable or patriotic position.

Q: Do you think the 1876 election was stolen?

A: I certainly do, although some historians feel it was justified because Hayes would have won if the Democrats hadn't intimidated black voters in sufficient numbers.

I give a lot of credit to Tilden. He said he wouldn't be seated at the point of a gun, and that was a powerful statement. If he'd said, "I consider myself president" and said he'd be seated, there may have been bloodshed.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.