Revisiting Black history through the eyes of Zora Neale Hurston

Loading...

“Negro folklore is not a thing of the past,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote. “It is still in the making.”

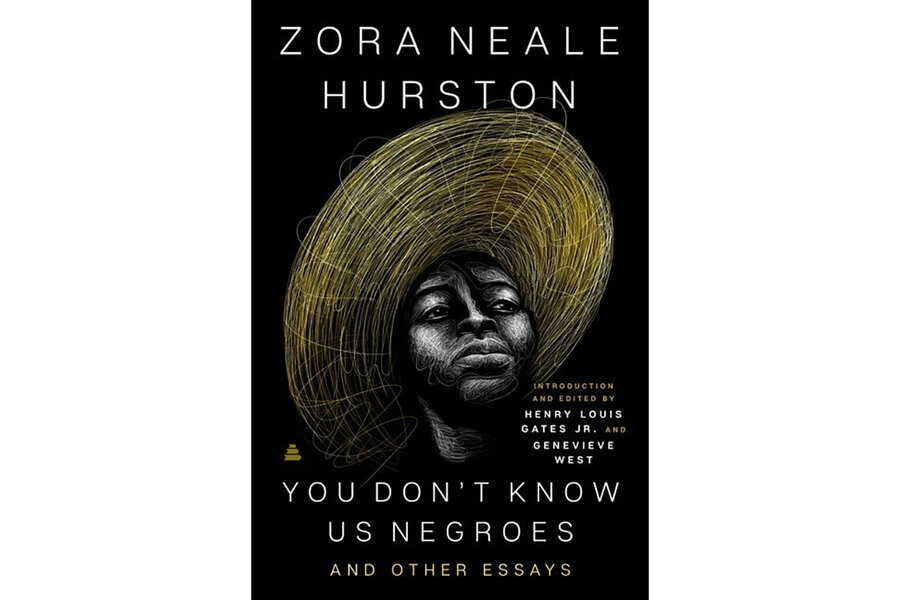

A new collection of Hurston’s essays and stories, edited and introduced by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Genevieve West in “You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays,” seems to prove her right. One hundred years ago, Hurston was attending Howard University, a historically Black college, as a young writer. Now a century later, this collection re-contextualizes both Hurston the writer and Black life in American culture.

Born in 1890s Alabama, Hurston spent her life observing Black people in her community and beyond. Through both her fiction writing and her anthropology work, she developed new ways of conceptualizing Black language, music, and culture. She insisted on capturing the nuances of Black people in the Americas and often used Black vernacular, or what is now called African American Vernacular English, in her writing. Her 1937 novel, “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” was initially panned by her contemporaries, who criticized it for its primary use of AAVE.

“You Don’t Know Us Negroes” is split into five sections to guide readers through Hurston’s writing. The last section is dedicated to Hurston’s reporting on, and observance of, the infamous Ruby McCollum murder case in Live Oak, Florida (more about this later). The rest of the collection oscillates effortlessly between folklore, Hurston’s reporting, and her essays.

The collection kicks off with “On the Folk,” in which Hurston explores various superstitions, language, cultural heroes, and tales from Black America. From slang to the spirituals of the church, Hurston traces the lineage of Black culture and its power to subvert white supremacy. Speaking of the presence of Black people in America, she writes: “He has modified the language, mode of food preparation, ... and most certainly, the religion of his new country.”

Readers are treated to sweeping examples of Hurston’s keen wit and her criticism of respectability politics, sexism, and classism. Throughout the collection, she takes unfaltering aim at issues not just outside the Black community but within it as well. In the eponymous essay, “You Don’t Know Us Negroes,” she points out that Black writers are partially at fault for the distortion of Black life in the general culture. An unwillingness to portray the fullness of Black culture, even the bad parts, has led to this, Hurston argues.

Her essay “The Ten Commandments of Charm,” in the third section of the book, feels timely given the ongoing revelations of the #MeToo movement. In it, Hurston cheekily and sarcastically details “commandments” for young women. “Thou shalt not ask questions,” Hurston writes. “Forget not thine femininity.” She advises young women to smile on the street, since that’s what men like. In a time when more women are coming forward about sexual harassment and abuse, Hurston’s writing, penned decades ago, rings even more true.

Her reporting on the 1952 McCollum case for the Pittsburgh Courier laid bare the harsh realities of Black women in the Deep South. The Black defendant was a married mother of four, who was charged with murdering C. Leroy Adams, a white doctor, whom she said had forced her into a yearslong sexual relationship. McCollum said that her youngest child was fathered by Adams. At the trial, she was denied the opportunity to tell her full story and explain her motives for killing Adams. The judge’s gag order prevented her and her lawyers from speaking to the press. An all-white jury found her guilty of first degree murder, and she was sentenced to the electric chair. The case was appealed, and the death sentence was eventually dropped in a plea deal, but McCollum, no doubt traumatized by her ordeal, was committed to a mental institution. (She was released in 1974.)

“You Don’t Know Us Negroes” is not light reading. It deals with complicated and raw topics that may be too intense for young readers. The collection is meant to be absorbed piece by piece, slowly, over time. It has much to offer but readers must take the time to fully read and appreciate the material.

While Hurston was a fierce protector and proponent of Black culture, she also wanted the “Black experience to speak in its own voice,” write editors Gates and West. She argued that it was the responsibility of the Black writer to “lift the veil” into Black life. Without a doubt, “You Don’t Know Us Negroes” does just that. This collection provides insights into Black language, culture, and history. But “You Don’t Know Us Negroes” is also a reminder that Black life is vast, nuanced, and (as Hurston put it) “a hundred times more imaginative and entertaining than anything that has ever been hatched up over a typewriter.”