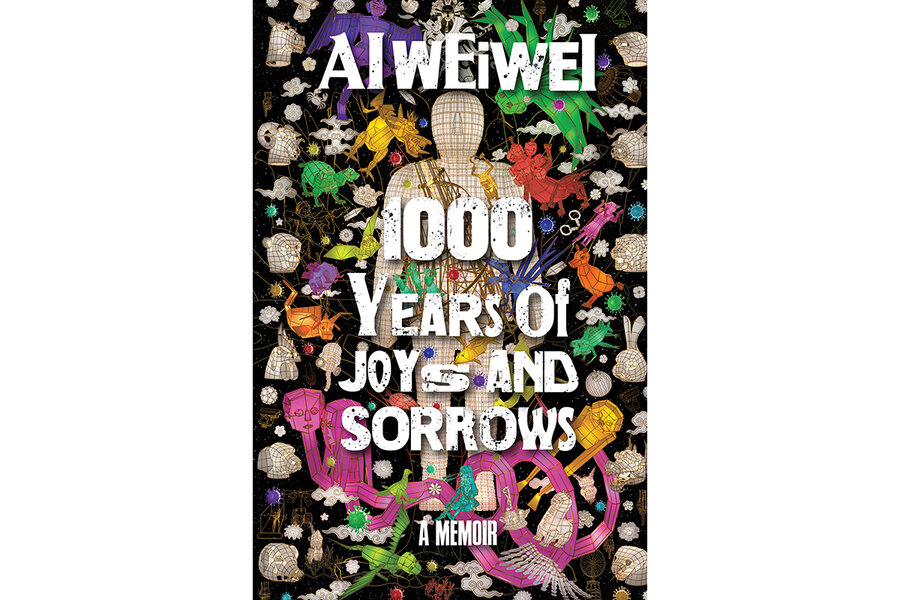

For Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, memoir as resistance

Loading...

Among the many reasons to write a memoir, the realization that the government could decide to eradicate any evidence of your lifework or even of your life might be the most extreme. Yet that was exactly what motivated Chinese-born artist Ai Weiwei to write “1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows.”

The art world superstar has built a career blurring the line between art and activism. While his sculptures, videos, and art installations have appeared in such august institutions as the Tate Modern and New York’s Park Avenue Armory, he has lived mostly in exile. The memoir, translated by Allan H. Barr, weaves together the story of his life with that of his father, celebrated Chinese poet Ai Qing who was banished in the 1950s as part of China’s Cultural Revolution. Originally intended to be an accurate account that Ai Weiwei could pass along to his own son, the book stands as a tangible record and proof of his resistance to the efforts of the Chinese government to “disappear” both him and his father. We simply become the beneficiaries of his documenting this remarkable story.

Ai’s childhood was shaped by China’s Cultural Revolution. Though his father had joined the Chinese Communist Party at that time and even counted Chairman Mao Zedong among his friends, the family’s life of comfort was short-lived. In 1958, as part of the effort to silence artists and intellectuals, the government exiled Ai Qing and his family, including 1-year-old Weiwei, to “Little Siberia” where Ai Qing was sentenced to years of hard labor and deprivation. It was not until Mao’s death in 1976 that they were able to return to Beijing.

Though the poet received an apology from the former minister of cultural affairs, Ai Weiwei recounts how the gesture rang hollow. Quoting his father, he shares the impact the exile had on the elder man’s writing, “It’s not easy to dredge up scattered memories from the bottom of the sea. Corroded by the seawater, many have lost their original luster. For so many years, I was cut off from the world.”

Both father and son endeavor to make up for lost time. The father published and traveled extensively, experiencing a portion of the acclaim that had been his due. The son, realizing that the Mao regime “had shaped – or deformed” his childhood, vows to leave China and finds his opportunity with the normalization of the country’s political relations with the United States In 1981, he acquires a passport and a visa that allow him to study in New York City.

Recalling that first flight into John F. Kennedy International Airport, he writes, “As I gazed down at the seething hallucinatory metropolis below, where traffic flowed like molten iron, all my motherland’s teachings, earnestly imparted over so many years, drifted away like smoke.”

His arrival marks the start of a successful career as he explores the work of Andy Warhol and develops friendships with such notables of the time as Allen Ginsberg. Ai grows from student to practicing artist, unafraid to speak the truth. He explains, “Because art reveals the truth that lies deep in the heart, it has the capacity to impart a mighty message.”

Ai’s growing success brings with it international notoriety. Choosing to live most anywhere but China, he realizes on a visit back to his homeland in 2011 how his own life experiences echo those of his father. Ai is secretly detained on accusations of tax evasion. The government locks him away for nearly three months. In prison, Ai realizes that his life and work could be destroyed, and all evidence of his existence erased. This volume stands as his defiance of that possibility.

In the book – which is both a historical account as well as a work of art – Ai weaves together his father’s story with his own, interspersing the narrative with reproductions of his father’s poems, his own drawings, and photographs and family snapshots.

Through memories and flashbacks, he shares his family’s experiences in exile, years spent in a crude earthen dugout enduring hunger and deprivation. It was the only life he knew as a child. As an adult, he came to appreciate how the circumstances impacted his father’s creative expression.

“1000 Years” stands as a testament to that creative spirit. A fascinating biography, it documents the history of modern-day China in which the son of a dissident could grow up to consult with the Chinese government on the “Bird’s Nest” stadium constructed for the 2008 Olympics. And though the iconic work drew the world’s attention to Beijing, Ai continues to live abroad to ensure his own artistic freedom.

What began as an account of two lives emerges as exquisite evidence of the invincibility of truth and creativity.