A family at the ‘Crossroads’ faces crises of faith and a test of its bonds

Loading...

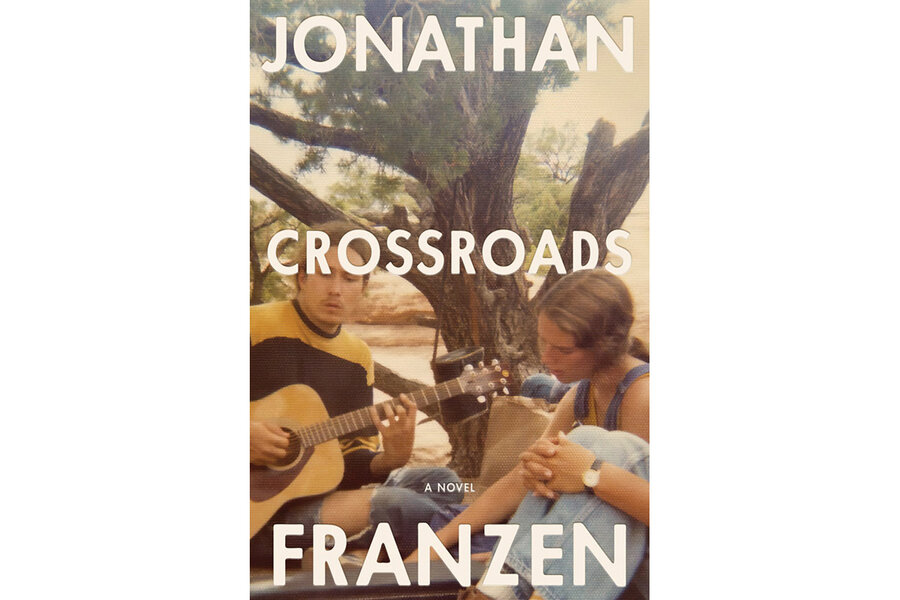

“Crossroads” is not only the title of acclaimed writer Jonathan Franzen’s latest novel, it’s also the name of a church youth group and the best word to describe the situation facing the Hildebrandt family.

Franzen unwinds the experiences of the Hildebrandts – a Midwestern pastor, his wife, and their four children – to examine the profound social upheaval of the 1970s. By showing the conflicts simmering inside and between family members, he teases out the struggle to find love and a sense of belonging.

We're first introduced to Russ, a husband, father, and associate pastor who fears that his sense of purpose has diminished and his coolness quotient has evaporated. He once collected blues records and marched with civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael. Now, however, he seems to be simply going through the motions of ministering to his flock. Russ, who is no longer attracted to his wife, entertains the possibility of an affair with a young, recently widowed parishioner.

His wife, Marion, has devoted herself entirely to motherhood, although she, too, has a complicated history and harbors secrets of her own.

Their children are wrapped up in their own worlds. Clem, the oldest child, is an honorable son who would make any parent proud. By going to college, he can obtain a draft deferment that will keep him out of the increasingly unpopular conflict in Vietnam. Becky parlays her good looks and popularity into power that she asserts over her circle of high school friends. And then there is Perry. Quiet, intense, a budding intellectual, he indulges in the ubiquitous drug scene.

The Hildebrandt offspring find their way to Crossroads, the youth group. While the aim is to draw young people into the church, one might question what they find when they get there. Crossroads is run by a charismatic young minister who leads the teens through pop-psychology exercises and well-intentioned charity projects, but the program’s success and the minister’s popularity have left Russ feeling diminished and humiliated.

Each member of the family hovers at a critical point, wrestling with issues both particular and universal, personal and societal, independent and connected.

In one plot thread, Clem informs the draft board that he will be dropping out of college and forfeiting his deferment. With his low draft lottery number, he knows that his decision all but guarantees that he will be called into combat. But that is his point. If he does not fight in the war, the obligation will fall to someone else. As someone who takes seriously the importance of social justice, Clem views his privilege as unethical and his choice as a means to build bridges with those whom society has marginalized.

While firm in his decision, Clem cannot bring himself to tell his father. As a young man, Russ had declared himself a conscientious objector. He considers all war to be unjust and unethical and those who fight to be contributors. Son and father, pursuing the same ideals, reach two strikingly different decisions. Their dilemma is just one of the seeming contradictions woven through the plot, differences that could fracture their family.

The novel teems with human foibles and missteps, with characters who pray for guidance but lack sufficient patience to wait for an inspired response. Each Hildebrandt seems to need to hit rock bottom before anything can change. Franzen writes of Marion, who comes to an epiphany of sorts, ”She wasn’t afraid of what was still to come, wasn’t afraid of ... dealing with the consequences, because her feet had found the bottom and beneath them was God. In coming to an end, her life had also started.”

Readers should be aware that Franzen minces no words as his characters deal with such issues as arson, rape, adultery, and drug use, to name a few. Some might find the language and the situations to be offensive and may wish to pass on this title. But for those willing to delve into the nearly 600 pages, they will discover individuals facing their crises of faith, sometimes drawing upon the same family bonds they once wished to sever.

This includes Russ and Marian, whose individual struggles bring them back to one another with new, hard-earned perspectives on life.

“I don’t deserve joy!” Russ tells his wife.

“No one does. It’s a gift from God,” Marion replies.