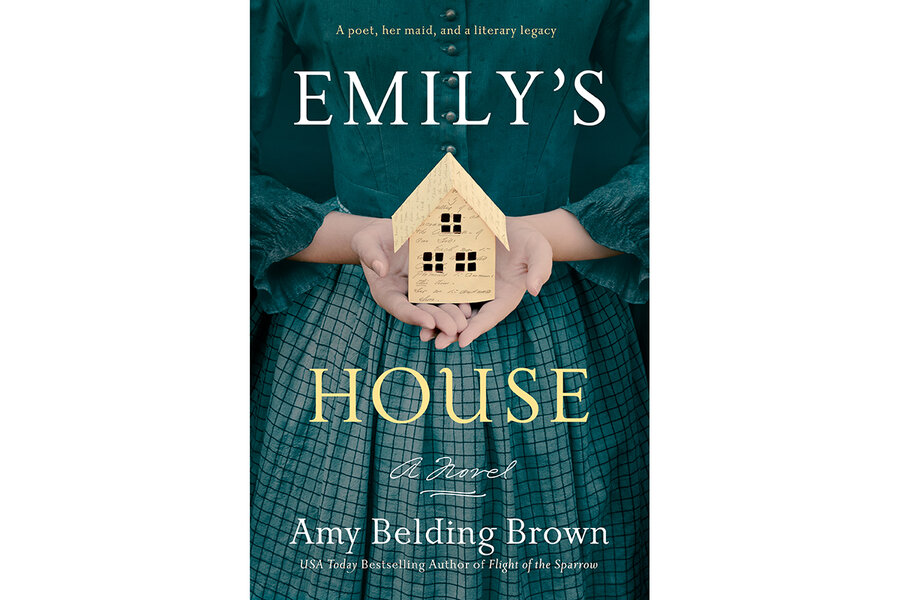

In the novel ‘Emily’s House,’ the Dickinsons’ Irish maid speaks her mind

Loading...

“More than once I’ve had the thought a life can be measured in doorways,” muses Margaret Maher at the start of “Emily’s House.” “I’ve learned to be a bit curious when a threshold’s being crossed.”

An Irish immigrant living in late 19th century Massachusetts, Margaret crosses thresholds major and minor throughout Amy Belding Brown’s bold and terrifically appealing novel.

Margaret works as a maid – and not just in any old house, mind you. She’s the lone servant in poet Emily Dickinson’s Amherst home, where she cleans, cooks, “wets the tea,” and tends to the needs of its affluent inhabitants: Father Dickinson, a local lawyer and landlord known as the Squire; Mother Dickinson, frail and fraught; grown daughter Vinnie with her cats and quirks; and reclusive, mysterious Emily.

Belding Brown, long a fan of Dickinson’s work, is a New England history buff (she also happens to be related to the poet). This love of place and ear for her characters’ turns of phrase makes for a rich reading experience. Her smartest choice: handing the narrative reins to Margaret herself, whose Tipperary-tinged voice guides – and warms – the story. It’s a perspective rife with honesty, humor, and sharp observations about class, immigration, and relationships.

In her first few years at the Dickinson house, called the Homestead, Margaret finds the residence too quiet and the family too remote. Worse, Emily insists on calling her Maggie – a nickname Margaret adjusts to, but never accepts. “Mam once told me the name Margaret means pearl. She said a pearl’s the only jewel that needs no cutting or polishing. Comes perfect from the hand of God Himself. And I ought to be treasuring myself like one.”

It isn’t until Emily suffers an accident in the garden, sending her upstairs to convalesce, that the relationship between mistress and maid begins to change. Following a night of storytelling and quiet companionship, both witness a dream-like scene in the street below. “That long, strange night, a bond formed between us,” reflects Margaret. “Over time it grew sturdy and limber and strong.”

As the relationship deepens, Margaret begins to play a more critical role in preserving Emily’s poetry (a fact Belding Brown uncovered in her research). While the family is vague about Emily’s pursuit and the poet herself surprisingly coy, the evidence of an artist at work starts to catch Margaret’s eye: quiet stretches behind closed doors, fragments of verse found in pockets, thick letters mailed to editors. When Emily finally divulges to Margaret the seriousness and scope of her writing, Margaret is moved to help organize and assemble the scattered verses into chapbooks. “I’ve always admired a poet,” she realizes, harkening to the Irish wordsmithing tradition back home.

And it’s a rich tradition, as evidenced by Margaret. While she doesn’t jot down inspirations, her own lyrical musings often rival Emily’s. At one point, Margaret observes that her mistress disappears into the house “like she’s made of the air itself”; at another, she sizes up a character “with his loud voice and great pillow of red hair atop his head.” Upon discovering Emily’s hidden stash of verses, Margaret breathes: “Like sparks they were – tiny scraps of light.”

Margaret’s awe runs counter to Emily’s misgivings about her writing – doubts that amplify as publisher rejections pile up and her health fades. In her anxious final weeks, Emily extracts a promise: Margaret will burn Emily’s work after she dies. It’s a vow that sits uneasily with the maid and results in an agonizing, and ultimately haunting, decision.

Belding Brown organizes the novel into sections named for parts of a house – thresholds, shutters, windows, doorways, chambers, corridors, porches. It’s a thoughtful way to underscore the importance of the Homestead to both women. For Emily, it serves as refuge, inspiration, and foundation. Margaret’s feelings about the house are more complicated; for her it’s a source of provision, a place of entrapment, an enabler of belonging, a bastion of secrets.

In a fascinating author’s note, Belding Brown explains the extensive research that went into her novel, and the truths that came to light after reading both an account of Margaret’s life and the letters of Emily’s niece Martha. The novel blends these facts and real-life characters with plausible but fictionalized subplots and settings pulled from the headlines of the era.

By the end of this gratifying, intelligent tale, a variety of readers – from Emily Dickinson neophytes to students of her work – will leave with a more nuanced understanding of “the myth of Amherst,” as well as a deep appreciation for the “wild and warm and mighty” woman who stood by her side in life, enabling a legacy.