Jane Goodall finds reasons for hope for the planet’s survival

Loading...

Jane Goodall is no glib Pollyanna. She writes in the opening chapter, “Probably the question I am asked more often than any other is: Do you honestly believe there is hope for our world?” She is unflinching in her assessment of the dire state of our planet. Yet she maintains that there is a window of time in which we can still repair much of the harm inflicted on the natural world – but in addition to hope, there is a need for action, engagement, even anger. Not new ideas, of course. But even for this initially cynical reader, Goodall’s eloquent reflections prove strikingly persuasive and often profoundly moving.

Why We Wrote This

As climate urgency mounts, optimism about the future can be hard to muster. But for Jane Goodall, hope is more than a balm; it’s what “enables us to keep going in the face of adversity.”

Imagine long leisurely evenings alongside Jane Goodall, perhaps on the veranda of her house in Tanzania. As the sun slowly sets, she recounts stories, experiences, and insights from a lifetime as one of the world’s most renowned primatologists and an impassioned climate activist.

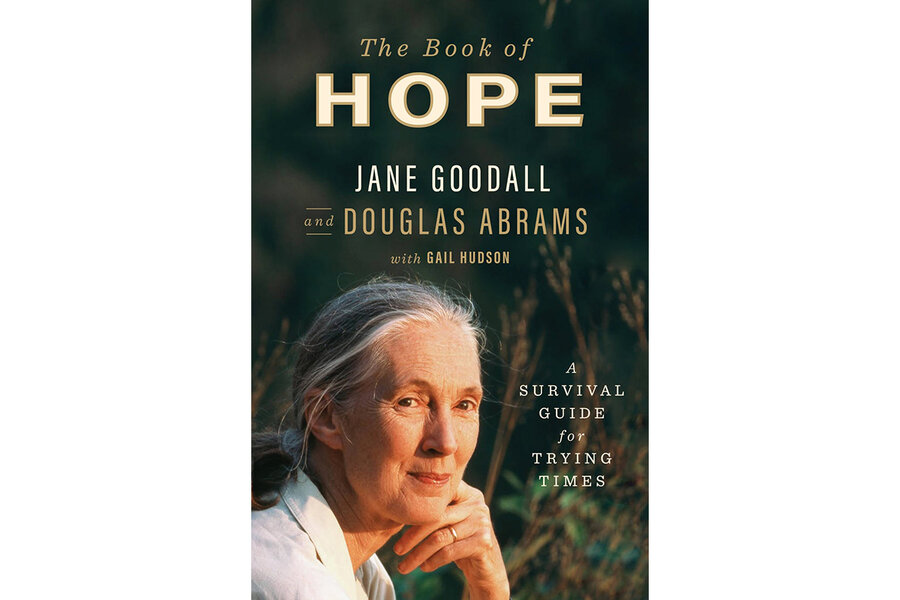

That’s a bit how “The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times” reads. Goodall’s new book, with writer Douglas Abrams as the reader’s inquisitive stand-in, unfurls as a series of engaging conversations and fascinating stories that Goodall hopes will touch the heart as well as the mind, with Abrams teasing out her thoughts and ideas. Through substantive interviews, we get a sense of a lively woman of brilliant intellect, keen insight, and impish humor, soft-spoken and empathetic yet passionate. The book also clearly demonstrates that Goodall’s urgency surrounding the issue of climate change is allied with hope.

Goodall is no glib Pollyanna. She writes in the opening chapter, “Probably the question I am asked more often than any other is: Do you honestly believe there is hope for our world?” She is unflinching in her assessment of the dire state of our planet. Yet she maintains that there is a window of time in which we can still repair much of the harm inflicted on the natural world – but in addition to hope, there is a need for action, engagement, even anger. Not new ideas, of course. But even for this initially cynical reader, Goodall’s eloquent reflections prove strikingly persuasive and often profoundly moving.

Why We Wrote This

As climate urgency mounts, optimism about the future can be hard to muster. But for Jane Goodall, hope is more than a balm; it’s what “enables us to keep going in the face of adversity.”

Goodall defines hope as a survival mechanism that “enables us to keep going in the face of adversity.” She points to four main reasons for hope, which form the book’s chapter titles: “the amazing human intellect, the resilience of nature, the power of youth, and the indomitable human spirit.” She illuminates the interconnected tapestry of life with extraordinary tales of animals and plants brought back from the brink. “I truly believe nature has a fantastic ability to restore itself after being destroyed, whether by us or by natural disasters. Sometimes it restores itself slowly, over time. But now, because of the terrible harm we are causing on a daily basis, we often need to step in and help in the restoration,” she says.

Throughout, the book is seeded with captivating photos that bring people and places to life. We get glimpses of Goodall’s remarkable life, from a shy, sickly child dreaming of studying animals in Africa to a trailblazing researcher whose time in the wild with chimpanzees led to challenging the reductive notion that human beings are different from and superior to all other animals. A popular speaker and gifted communicator, she now travels the world to “wake people up,” trying to inspire respect for all life and a commitment to preserve it.

At times, the book’s digressions and repetitions impede the flow, and the conversational tone can get a bit cloying. The meat of Goodall’s wisdom could have made for a slimmer, pithier read. But Abrams is especially effective as devil’s advocate when his skepticism kicks in and he challenges, pushing for clarity. And Goodall never fails to rise to the occasion. One fascinating exchange delves into – with a thoughtfulness totally devoid of didacticism – the convergence of science, religion, and spirituality, referencing Shakespeare, philosophers, and Einstein’s “harmony of natural law.”

The book ends with a direct “Message of Hope from Jane,” which broaches the topic of new human diseases that researchers say come from our interactions with animals (like COVID-19). She says that in addition to defeating these diseases, we must fight against “stupidity, greed, and selfishness.” And she assures us that “the cumulative effect of millions of small ethical actions will truly make a difference.”