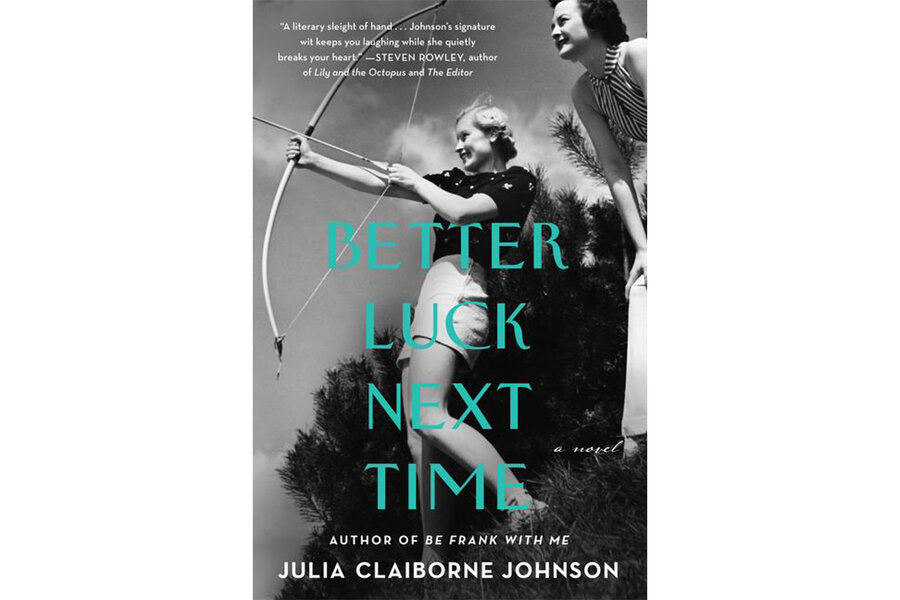

‘Better Luck Next Time’ calls to mind screwball comedies of the 1930s

Loading...

As a young bride, one of my stranger initiations into my husband’s family involved hearing stories about his step-grandmother’s disappointing first marriage and six-week stay on a Western dude ranch in the 1930s – which enabled her to establish Nevada residency and subsequently procure a quick Reno divorce. Her first husband, she told me, had grown older but had never grown up.

Her course of action was not unique; in fact, an entire business had developed around the needs of women in her situation. Julia Claiborne Johnson’s fun second novel, “Better Luck Next Time,” takes readers to one so-called divorce ranch in 1938. The book channels Frank Capra’s screwball comedies, and more specifically, George Cukor’s hilarious 1939 movie version of Clare Boothe Luce’s play “The Women” – in which much of the all-female, all-star cast (Norma Shearer, Rosalind Russell, Joan Crawford, and Paulette Goddard) also land on a Reno divorce ranch.

Johnson frames her story through memory, in the spirit of the coming-of-age film “Summer of '42.” Her male narrator, Howard Stovall Bennett III, a retired southern doctor better known as Ward, wistfully recalls the summer of ’38. This was his last season working at the amusingly named Flying Leap ranch as a pseudo-cowboy and gofer. His main job was to squire – or wrangle – the wealthy women that the ranch catered to.

Ward’s recollections are spurred 50 years later by an unnamed visitor at his nursing home in Whistler, Tennessee. The visitor tells the retired doctor that he is writing a book about divorce ranches and asks to record their interviews.

Prompted by a group photograph of the guests and staff of the Flying Leap from that pivotal summer, Ward happily dives back into the past. Hobbled by a wartime back injury, and with no wife or children (“not that I know of, anyway, ha ha”), he’s glad to have a rapt listener. Despite the decades that have passed, he recalls the hijinks and heartaches from that year in sharp detail. With less relish, he recalls how he landed at the ranch after his parents lost their stately home and comfortable livelihood during the Depression, forcing him to withdraw from Yale.

Ward’s voice is homey and – presumably deliberately – cliché-ridden. His tale centers on two striking, well-to-do women in their 30s; both arrive at the ranch on their own steam, take to each other immediately, and co-opt young Ward (who is said to look like Cary Grant in cowboy boots) to squire them around.

Emily Sommer, petite, dark-haired, with “the plummy accent of women who cycled through the Seven Sisters colleges back East,” drives herself from San Francisco, quaking with distress the whole way, in the cashmere-upholstered Pierce-Arrow she’d bought for her philandering husband Archer. (Archer chose the car because of its self-referential hood ornament – a little man with a bow and arrow.)

Tall, blond, adventurous, bitingly witty Nina O’Malley, a repeat customer, flies herself in from St. Louis in her double-cockpit biplane for her third divorce. (Her first was from her flight instructor, whom she married at 17.) This is a character who “believes that anything worth doing is worth overdoing.” She channels Carole Lombard with a touch of Katharine Hepburn, and gets all the novel’s best lines. Asked why she became an aviatrix, she quips, “I took up flying airplanes because I enjoy looking down on people.”

Johnson sets the tone for the novel’s spiky take on marriage with epigraphs from Zsa Zsa Gabor and Groucho Marx, which are complemented by the zingers Ward reports having heard at the ranch, including, “He was taller when he was sitting on his wallet.”

Emily is torn about her divorce – and she’s not the only one. Her split is complicated by desperation to appease her scornful teenaged daughter, whom Archer sends out for a visit as a last-ditch effort to hold onto his rich wife. Nina reminds Emily, “You don’t stop mattering once you give birth, you know,” and urges her to be less cautious and more thrill-seeking. Emily tries, with mixed results.

Johnson spins a madcap plot with more twists than a Tiffany braided gold choker. There are confidential conversations overheard by the wrong people, and trysts not quite hidden by “the earth’s nocturnal gaffer, the moon.” Johnson carefully sets up her punchlines, often with physical comedy, including ridiculous masquerade costumes and mistaken identities. At a particularly inopportune moment, Emily’s underwear is found scandalously clipped to the Pierce-Arrow’s hood ornament.

This is a novel fueled by secrets. Ward’s decision not to reveal his background leads to painfully condescending treatment, especially by Emily, who marvels at his good manners considering his lowly status, and calls him a diamond in the rough. In keeping with the times, Nina won’t name the reason why her third marriage to a man she clearly still loves can’t work.

“Better Luck Next Time” takes its title from what the Reno judge purportedly said “every time he gaveled a woman from wife to divorcee.” Without giving away too much, I can say that, in an ironic twist, there is no next time for most of these characters. But there is a delightful sense of closure in the way Johnson wraps up this shiny package, which arrives just after New Year’s like a late holiday gift.

Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for the Monitor, The Wall Street Journal, and NPR.