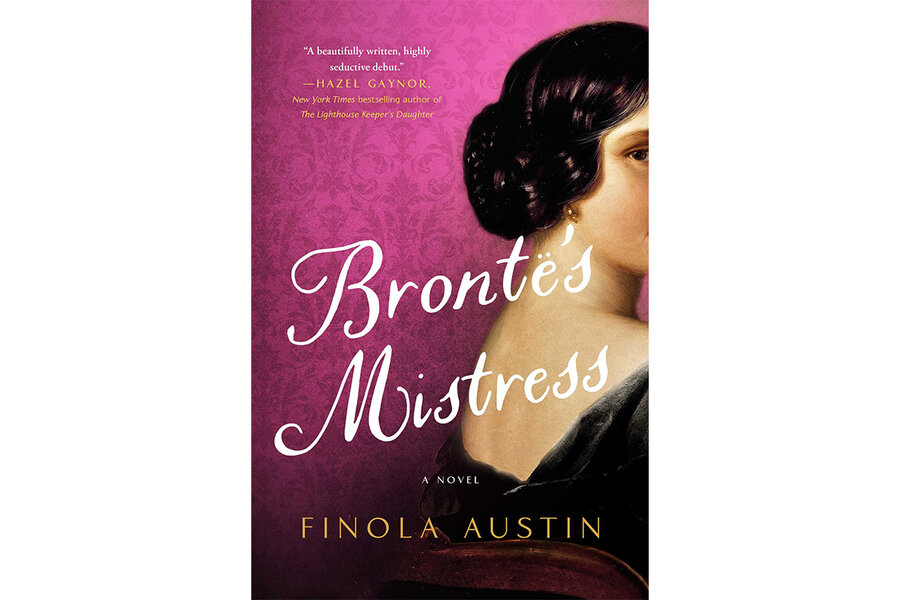

‘Brontë’s Mistress’ may speculate, but it does so delightfully

Loading...

Finola Austin writes in her author's note, “Brontë’s Mistress is a work of fiction,” and she adds, “I don’t pretend that it records what happened between Lydia and Branwell, but given the facts at our disposal, it imagines what could have happened.”

The Lydia she mentions is Lydia Robinson, wife of Rev. Edmund Robinson, who in 1843 hired a dashing young tutor for her children at Thorp Green Hall, a few miles northwest of York. The young tutor, Branwell, came highly recommended by the children’s previous governess: Branwell’s sister Anne.

Lydia is also the mistress of the novel’s title, the narrator who tells the story of her affectionate but passionless marriage, her adorable but demanding children, and the sudden longings she feels when presented with this new young man in her life. “After all, Edmund had refused to make love to me,” she thinks at one point. “And I had not been ready to live only on memories.”

It’s a charged plot for a novel. In July of 1845, the historical Branwell really was abruptly dismissed from his post by Reverend Robinson, and energetic rumors immediately abounded. Did Branwell’s drinking, already a problem, prompt the dismissal? Or his boastful nature? Did he, as some of the darkest speculation has tendered, attempt abuse of some kind with the Robinson’s young son? Or, as the bulk of the speculation ran, was he dismissed because he had an affair with Lydia?

The last of those scenarios was enthusiastically put forward by Branwell himself, who boasted to correspondents that his employer's wife was rather too fond of him, that he kept a lock of her hair, and so on. And a variation of this picture was immortalized by Elizabeth Gaskell in her 1857 biography “The Life of Charlotte Brontë,” in which she risked a libel action when she all but accused Lydia Robinson by name of seducing Branwell and leading him into “the deep disgrace of deadly crime.”

Debate over what happened at Thorp Green has raged ever since, in scholarship and in fiction, in novels like Douglas A. Martin’s 2005 “Branwell” and in impassioned nonfiction like Daphne du Maurier’s 1960 “The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë.” Did Branwell initiate the relationship? Or, as Gaskell insinuated, was he seduced, at age 28, by a 43-year-old woman? What was the nature of the incident that enraged Reverend Robinson so much that rumor had it he threatened to shoot Branwell if he ever returned to Thorp Green?

For her fiction debut, Finola Austin has opted for a more or less straightforward Hollywood story of spontaneous, mutual love. Handsome young Branwell, his hair mussed and his shirt falling open, arrives in the cold and loveless world of Thorp Green, and in short order he and Mrs. Robinson are forging emotional connections. “It was ridiculous,” narrates Lydia. “Me, with wet hair, in a gown too frivolous for a housekeeper to see me in ... and the unkempt tutor playing the eccentric poet. I laughed, and, while Mr. Brontë looked puzzled, I felt a new fragile bond forming between us.”

The bond causes trouble. Inevitably, Anne discovers it (“But it isn’t as you think,” Lydia protests to her), and the rest of Thorp Green isn’t far behind – including Reverend Robinson, a powerful man whose strange combination of stillness and rage makes him the novel’s most interesting character.

Austin can sometimes lapse - or allow Lydia to lapse - into the kind of breathless prose more endemic to old-fashioned romance novels. “The music washed over us in wave after cleansing wave. I knew – hoped – that Branwell heard in the music what I heard, that his soul was vibrating at the same frequency as mine,” we’re told at one such point.

But the bulk of the novel’s momentum builds a convincingly multifaceted picture of Lydia, a smart, passionate woman who is caught between her own thwarted desires and the gears of society’s conventions. Austin grounds her book in research, but it’s the entirely fictional letters she intersperses throughout the book that truly bring Lydia and many of her other characters to life.

And the mystery? Well, unless some new batch of records comes to light, it will no doubt continue to be a bone of contention for Brontë scholars – and a fruitful ground for novelists. Austin has written a stirring defense of the maligned Mrs. Robinson, and who can say if it isn’t also the truth?