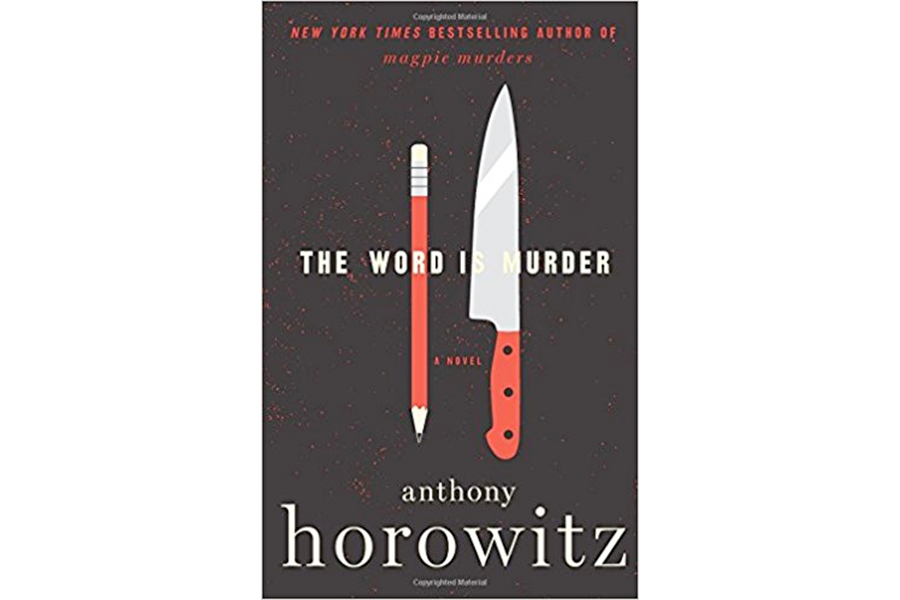

'The Word Is Murder' is Anthony Horowitz at his ambitious best

Loading...

Forget about the wonders of Sherlock Holmes and James Bond. What this reader wants to know is when, or whether, Anthony Horowitz ever sleeps.

Horowitz, aptly described on his website as a polymath, is that and more. The British writer counts Holmes and Bond as iconic characters whose literary legacies he has expanded into the 21st century, earning kudos from readers and reviewers alike. That’s a mere fraction of his creative output, though.

Teen readers know Horowitz for his "Alex Rider" adventure novels, spanning 11 books and 19 million copies sold. He’s also the creator of the long-running British detective series “Foyle’s War,” set during World War II and, later, the Cold War.

More recently, Horowitz has focused on stand-alone mystery novels aimed at adults. Last summer brought “The Magpie Murders,” a mash-up of Agatha Christie-style whodunit with affectionate tweaks of the clubby world of British publishers, editors, and authors.

And now comes “The Word Is Murder,” a bit of meta-fiction told by a writer named Anthony Horowitz, whose works include a couple of Sherlock Holmes novels, the "Alex Rider" series, and “Foyle’s War” on TV. This alter-Horowitz encounters a former British detective – a consultant on a series called "Injustice” starring James Purefoy (everything but the former detective being true to life) – who wants Horowitz to write a nonfiction account of his investigative methods.

The former detective, Daniel Hawthorne, irritates and frustrates narrator Horowitz at almost every turn. But the fictional version of Horowitz, probably much like the author himself, can’t resist a great story. Or, rather, the potential for a great story.

Hawthorne hooks Horowitz with a whopper of a set-up: He’s helping the police look into a most unusual murder, committed days earlier.

A woman named Diana Cowper, healthy and in her 60s, entered a London funeral parlor, where she planned and paid for her own future service, picking out the music and readings while imploring the funeral director to make sure her funeral doesn’t drag on too long when the day comes.

Six hours later, she’s dead, strangled with a red curtain cord. Two days after that, Diana Cowper’s corpse comes to light, discovered by her housekeeper.

As Horowitz writes, “Think about it. Nobody arranges their own funeral and then gets killed on the same day.”

It’s an intriguing story. And it gnaws at Horowitz even as he tells Hawthorne he has no interest in writing true crime. Horowitz insists he’s a novelist and TV writer, a creator who revels in controlling his stories with the latitude fiction affords.

Which means Horowitz is absolutely going to collaborate with Hawthorne despite his disdain for the blunt-spoken, often secretive police consultant.

And, Horowitz discovers, Hawthorne might be annoying, cheap, and gruff, but he has a knack for getting people to reveal important details.

“He came across as ordinary, even obsequious,” Horowitz writes, describing the other Horowitz’s initial impressions. “The more I got to know him, the more I saw that he did this quite deliberately. People lowered their guard when they were talking to him. They had no idea what sort of man he was, that he was only waiting for the right moment to dissect them.”

For a portion of the novel, Horowitz and the reader alike don’t know why Hawthorne left the police. All that’s known is the police fired him for unknown reasons after 10 years as a murder investigator.

Those circumstances led to a second career as a consultant on TV crime procedurals and the occasional, discrete freelance job helping the police with difficult cases. Hawthorne tells Horowitz one of the down sides to his part-time investigations is there just aren’t enough murders to keep him gainfully employed.

The Cowper case, though, proves worthy of his time – and Horowitz’s. Beyond the eerie and all-but-impossible coincidence of her death, Diana Cowper, it turns out, was the mother of a fast-living Hollywood movie star. And, to further complicate matters, Diana Cowper, 10 years earlier, while driving in a seaside town in England, got behind the wheel without her glasses and ran over twin 8-year-old boys who darted into the road. One of the boys died and the other suffered permanent injuries. The boys’ parents were shattered and remain embittered over the accident, especially since Diana Cowper avoided jail and any significant punishment.

These threads, along with a drama school rivalry involving Diana Cowper’s future movie star son, provide more than enough material for Horowitz to feint this way and that before revealing the killer and, just as important, the killer’s motivations.

Much like “The Magpie Murders,” Horowitz succeeds with “The Word Is Murder” by simultaneously adhering to and defying the rules of a traditional mystery. As for the mystery of how Horowitz keeps turning out so much good work in such short order, it’s hard to say. Especially when confronted with this piece of news: In Horowitz’s native England, his second Ian Fleming estate-endorsed James Bond novel, “Forever And A Day,” has just been published and is earning solid reviews.

Since “The Word Is Murder” is just arriving in the US, American readers will be forced to wait until November before “Forever And A Day” is released here.

And what next beyond Bond for Horowitz? No clue, but odds are it will be fun.