'The Seventh Most Important Thing' is a remarkable tale of redemption for middle-grade readers

Loading...

The first sentence of this remarkable book ends with a wow: "thirteen-year-old Arthur Owens picked up a brick from the corner of a crumbling building and threw it at an old man's head."

After reading that, who could possibly put aside The Seventh Most Important Thing, Shelley Pearsall's newest middle-grade novel (ages 10 and up)?

Arthur lives with his mom and younger sister in Washington DC. Even though his father was far from perfect, Arthur grieves for the recently-deceased, motorcycling, hard-living man. But he's not ready to fill his shoes, give up the memories, or forgive his mom for tossing his dad’s belongings. In fact, the seventh grader is pretty much mad at the world, at the vice-principal of his school, at the bullies who taunt him. Most days, even his sister aggravates him. And now he's furious at the raggedy old Junk Man wearing his dad's favorite hat.

Fortunately for Arthur, the Junk Man survived the tossed brick. Even better, he's working on an amazing project in a garage behind a tattoo shop. The Junk Man himself speaks to the judge. Instead of incarceration, Arthur is offered redemption. The boy will be required to help James Hampton, artist and collector of interesting objects, known around the neighborhood as the Junk Man.

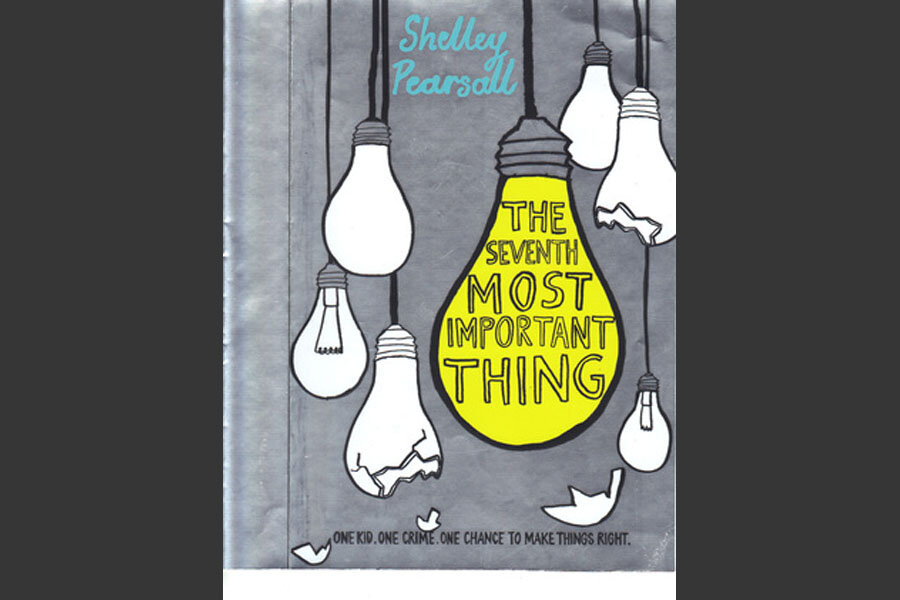

There are so many things to love about this book. Arthur's perfect voice, spare, honest, revealing. The stark, intriguing cover design of dangling broken light bulbs and the description under the title – "One kid. One crime. One chance to make things right."

That title refers to the list Hampton gives to Arthur when he arrives to begin his redemptive work. Although mystified at first, Arthur soon realizes he's being asked to push a rusty old cart and collect those seven things. He's not been sentenced to assist the Junk Man. He's "been sentenced to be the Junk Man."

Helped by an appealing, slightly nerdy new school friend named Squeak, "the kind of person who followed directions 100 percent" and his patrol officer, another great character, Arthur begins to pay his debt to society and to the Junk Man.

There are so many things that made me laugh while reading this book. Squeak brings his lunches to school in perfectly-wrapped squares of aluminum foil. Arthur remarks that “juvie” (where he spent the weeks before his sentencing) is “practically a bully vacation spot.” Humor helps lighten the serious story, and Arthur’s story is serious. Because in the end, the young man does learn the meaning of redemption.

Although "The Seventh Most Important Thing" mostly takes place in Washington DC in 1963 and 1964, the novel has an extremely readable timelessness to it. The reason for that place and those dates becomes clear upon reading Pearsall’s Author's Note. Yes, “The Seventh Most Important Thing” is based on a work of art. But even without the history, this story will resonate with readers, young and old.