'De Niro' is impressive, fair-minded, and doesn't shrink from tough questions

Loading...

Few actors since Orson Welles have been as admired – or as condescended to – as Robert De Niro.

Both burnished their reputations early on: Welles for his breathtaking screen presence in “Citizen Kane,” De Niro for his vigorous incarnations of morally knotty characters in such films as “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull.” And both were deemed disappointments as they got on in years: Welles for his ubiquity in déclassé television commercials, De Niro for appearing in a number of artistically unsound films.

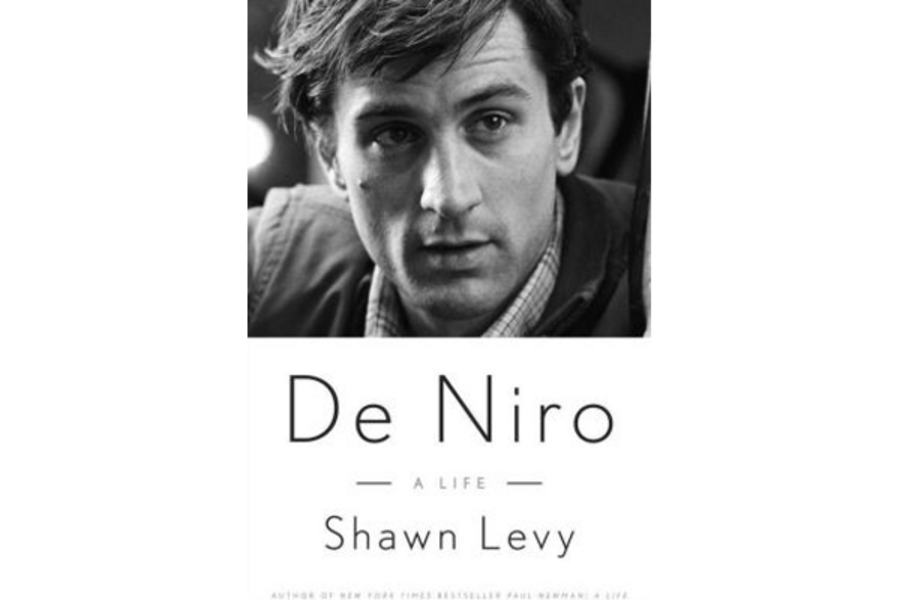

This dichotomy is tackled head-on in Shawn Levy’s De Niro: A Life, an authoritative biography that impresses with its fair-mindedness. While Levy, also the author of earlier biographies of Jerry Lewis and Paul Newman, is unstinting in his admiration for De Niro’s best films – including a five-year period that netted “Mean Streets,” “The Godfather Part II,” “Taxi Driver,” and “The Deer Hunter” – he does not shrink from acknowledging what is on all of our minds: De Niro has traded delving deeply into characters like “Raging Bull” boxer Jake LaMotta for low-maintenance roles. Arguing that De Niro’s work (and the projects he opted to work in) could be depended on as late as the 1990s, Levy admits that, in the aftermath of the blockbuster success of “Meet the Parents” in 2000, “the arithmetic he did in choosing roles changed, and he began making films out of dubious material with scripts and co-stars and directors that left audiences puzzled why De Niro was involved.”

Indeed, the book – tethered as it is to the yo-yoing of De Niro’s career – winds down on a glum note, with Levy marching through such films as “City by the Sea” (“the first film to truly mark a dip in his interest in his work”), “Righteous Kill” (“a strictly by-the-numbers crime movie”), and, of course, the sequels to “Meet the Parents” (“‘Little Fockers’ ... was about as subtle and nuanced as a steamroller leveling a fruit stand”). (Levy’s pithy, consistently erudite descriptions of films is a carryover from his background as a film critic.) Setting aside the aberration of “Silver Linings Playbook” – for which De Niro was Oscar nominated – Levy is forced to conclude that, “for reasons that were genuinely unclear and even troubling,” the actor’s taste in roles had slipped miserably.

“Once his talent had seemed like vintage wine, carefully decanted drop by painstaking drop into the finest crystal,” Levy writes. “Now he was pouring it sloppily into so many paper cups as if it were the cheapest, most indifferently made plonk.”

Of course, several hundred pages precede this despairing conclusion – pages which recount, in frequently minute detail, the making of De Niro’s earlier triumphs. Jam-packed with insight, anecdotes, and trivia about those films, it is almost enough to make us set aside the paper cups and plonk and treasure the wine and crystal.

Levy has the gift of breathing life into films that have been written about to death, as when he emphasizes how perilously close “Taxi Driver” came to not being made: director Martin Scorsese and producers Michael and Julia Phillips were busy with other projects, and De Niro could have earned far more than his $30,000 salary. According to screenwriter Paul Schrader: “He was being offered a half a million for something else.”

As we read of De Niro’s working methods, which involve not only fulsome research but his own sometimes-philosophical musings on a given character, it is a pleasure to summon our memories of the final performances, matching the process with the end result. For example, we learn that De Niro visualized a crab when reflecting on “Taxi Driver’s” cab driver antihero Travis Bickle: “He’s out of his cab, which is his protective shell – he’s outside his element.... I got the image of a crab, moving awkwardly, sideways and back.” Playing stylish studio executive Monroe Stahr in “The Last Tycoon,” De Niro luxuriated in his fancy wardrobe, wearing it even when not filming: “I spent time just walking around the studio dressed in those three-piece suits, thinking, ‘This is all mine.’” Levy suggests that De Niro looks for himself in many roles, as in script notes for “Stanley & Iris” in which he compares the illiteracy of his character to “his very limited knowledge of Italian.”

Levy also prepares us, in a way, for De Niro’s drop off, pointing out that, four short years after “Raging Bull,” he was in his first genuinely insubstantial film (“Falling in Love”) and four years after that, he was in an outright comedy (“Midnight Run”). And Levy makes clear that De Niro did not always have the pick of the litter. Writing of the tacky Ma Barker crime film “Bloody Mama” – made early in his career – Levy commends De Niro for being “the most haunting thing in a surprisingly haunting bit of grindhouse,” praising his performance for the sort of character specificity we associate with his finest hours, such as “his habit of falling into distracted singsong” or “wearing a fedora with the brim turned up,” the latter a detail he recycled in “Mean Streets.” Maybe De Niro was always less pure than we imagine, appearing – for far longer than just the past decade – in humdrum films.

In the end, though, perhaps we should look to Orson Welles himself to best understand De Niro’s career fluctuations: as Peter Bogdanovich has recalled, Welles responded to Bogdanovich’s comment that Greta Garbo made just a pair of good movies by saying – after a pause – “You only need one.” And Robert De Niro has many more than that.

Peter Tonguette’s criticism has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard, National Review, and many other publications.