A Broken Hallelujah

Loading...

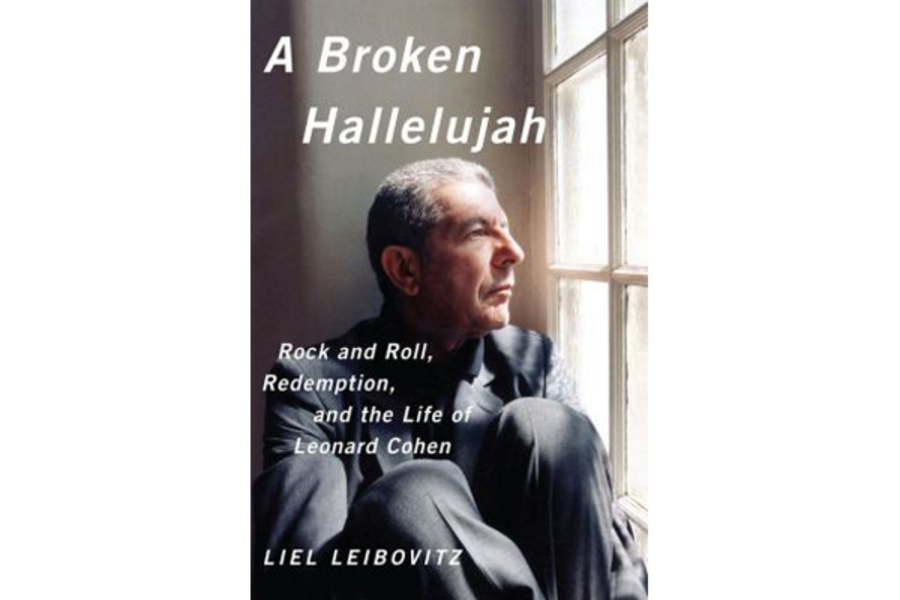

"This is not a biography of Leonard Cohen.” This is the opening sentence of Liel Leibovitz’s thoughtful, ruminative A Broken Hallelujah: Rock 'n' Roll, Redemption, and the Life of Leonard Cohen.

A book that promises the “Life of Leonard Cohen” in its subtitle might be sending mixed messages. One can assume that Leibovitz wants to put a little distance between himself and previous writers who did not eschew the title of biographer. English professor Ira Nadel interviewed Cohen and many of those around him for his "Various Positions"; Sylvie Simmons gave Cohen the full-on life-in-showbiz treatment in "I’m Your Man," where she had access to nearly everyone, but did not know exactly what to ask.

In distinguishing himself from these predecessors, Leibovitz lets us know that his book will have a depth worthy of his subject. 2014 happens to be the year of Cohen's 80th birthday, and Leibovitz’s book is among nine Cohen books to be published this year. So what word is more suited than biography? Philosophical tract? Poetic meditation? Spiritual odyssey? Lyric essay? All of these might apply – not unlike his subject, Leibovitz is inclined to aim for lofty realms in which mere information seems a small affair.

Since the Nadel and Simmons books, Cohen, who was forced to tour after a manager robbed him blind, saw his stock rise like never before. He was filling sports arenas and hearing covers of “Hallelujah” crop up all over the place, even on "American Idol". Even as he was constantly onstage and in creative overdrive in the studio, he also suddenly became conspicuously unavailable. On his most recent album, "Old Ideas," Cohen plays with this notion, claiming to be inaccessible even to himself: “I’d love to speak with Leonard/ He’s a sportsman and a shepard / He’s a lazy bastard living in a suit.”

Cohen is joking of course, something he does more often than you would know in this learned, eloquent, and rather maudlin tome. Cohen has been on the road since 2008, and between sets, he hops across the stage, with a delirious smile on his face. It’s a long way from The New Yorker’s 1993 description of him as the “Prince of Bummers.”

But it is the Prince of Bummers who dominates Leibovitz's’s book, and we are given evidence for why he was so anointed. He has been a man who appears to have been, as the man himself once put it, sentenced to death by the blues. We follow Cohen’s despair, losing his father at the age of nine, living off his family fortune as a poet in Montreal, New York, and Greece. Cohen has said that, like many young men, he wrote poetry to attract women, and when that didn’t work, he appealed to God. Really, in the tradition of John Donne, he was sometimes doing both in the same place, as in "Hallelujah," his most celebrated song.

While Leibovitz is artful and precise in his descriptions – the best of which is a stunning, blow-by-blow account of Cohen's appearance at the tumultuous Isle of Wight festival in 1970 – the Cohen of this book is somewhat joyless. So we get descriptions of his initial discomfort in the recording studio, and of the obtuse reviews of his debut, The Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967). We get Cohen having a series of nervous breakdowns onstage and backstage; we learn that Suzanne Elrod (not the Suzanne of the song) waged a custody battle for their children without witnessing him exhibit any joy as a father. His relationships with various women end, but we never see the ebullience of their beginning.

What we don’t get is a sense of the triumph of an album that is one of the most astonishing debuts in the age of the LP, stuffed with masterpieces like “Suzanne,” “Master Song,” and “The Stranger Song,” among many others. Cohen may have been struck with self-doubt during the entire process, but for so many listeners, the album is a gift that keeps on giving. Bob Dylan was influenced by poetry (among many other things), and Jim Morrison (who is taken far too seriously in this book) had delusions of his own poetic stature, but it is Cohen, a fully formed poet – who had published two volumes of poetry and a novel before he wrote his first song – who combines high poetry with pop songwriting like no one else.

Such triumph amid despair should be at least intermittently satisfying, if not for the neurotic and self-abasing Cohen, then at least for his non-biographer. And Leibovitz offers windows to such wider horizons in many places in this book, particularly in his consideration of Cohen’s Jewishness and embrace of Zen Buddhism.

If you look deeply not just at Cohen but at what he read, whom he knew, and how he became the artist he became, there's plenty beyond the gloom. He gives it to all of us in the songs. A life of spiritual quest is bound for disappointment; Cohen at 80, is still writing, recording, and performing, but more reluctant to appear than ever. His exegetes have plenty of material on their hands, brimming with beauty and truth and still proliferating. There could never be a perfect account of the life of a man who is wise enough to eschew perfection itself, as he put it when he was around 60: “Ring the bells that still can ring / Forget your perfect offering / There is a crack, a crack in everything / That's how the light gets in.”