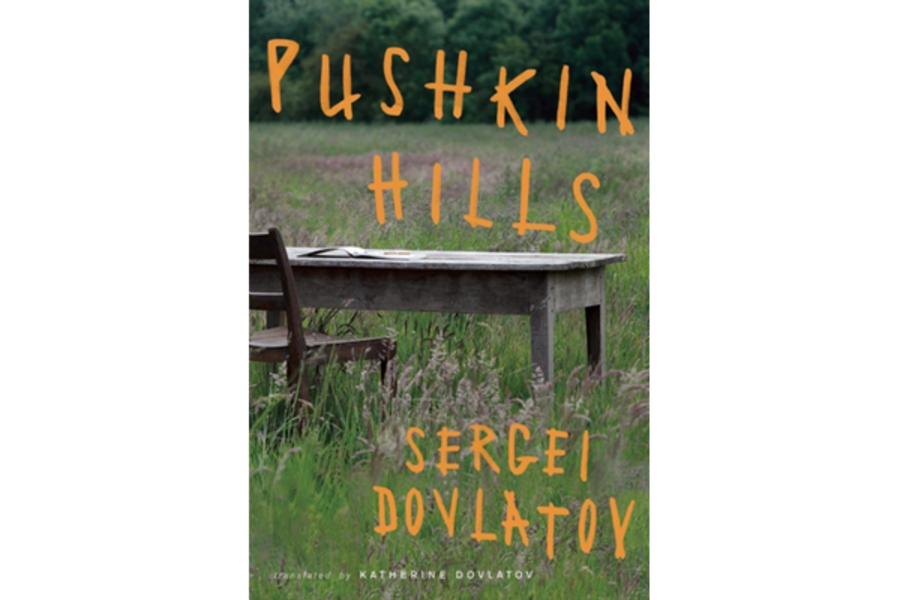

Pushkin Hills

Loading...

A new English translation of Sergei Dovlatov's 1983 novel, Pushkin Hills, begins with the dedication: "To my wife, who was right."

Dovlatov's wife was right, presumably, about lots of things, though it seems most likely Dovlatov is referencing her decision to move the family from Russia to the United States in 1978. In his lifetime, Dovlatov was never published in his mother country. Had his wife not made that call, his work might have slipped away, forgotten – even worse, never published.

The new translation was done by Dovlatov's daughter, Katherine, who told The Paris Review in a recent interview that her goal was "to keep the same musicality, the same tone.... And of course hearing my dad's voice helped, too." "Pushkin Hills" (originally translated as "The Preserve") is an autobiographical novel about a writer named Boris who decides to take a job as a tour guide at the Pushkin Museum and Preserve. Boris is unpublished and his life is in shambles – his ex-wife is about to move to America, taking their young daughter with her. He spends most of his time ruminating on his bad luck with a bottle of vodka.

Dovlatov enforced a strange rule on himself when writing: he never repeated a word that started with the same letter in the same sentence. Katherine explains it was a way to "slow himself down. It was meant to be a self-editing mechanism." Though in English it would be too difficult to replicate that method (English has too many articles), his daughter has captured the same sense of distilled wit in her translation. Dovlatov is known for his brief but efficient sentences. "The station: a dingy yellow building with columns, a clock tower and flickering neon letters, faded by the sun..." is how he describes the bus station at the preserve. "A cold shower worked like a loud scream." "Grimy sheep with decadent expressions grazed lazily on the grass." As Boris says of his writing sketches: "Dostoevsky used to say, 'a hint of greater meaning.' "

Boris is met with a crazy cast of characters at the preserve, including Mikhail Ivanych, an alcoholic par excellence who rents out a dilapidated room in exchange for booze, and fellow tour guide Mitrofanov, a genius ruined by laziness. "He possessed no other qualities. He was a genius of pure learning.... [He] grew into a fantastic sloth, if one can call lazy a man who had read ten thousand books." Boris, for his part, starts to reread Pushkin and is eventually motivated to write again. "What intrigued me most about Pushkin was his Olympic detachment. His willingness to accept and express any point of view. His invariable striving for the highest, utmost objectivity. Like the moon, illuminating the way for prey and predator both."

Boris's complacent routine is destroyed when his ex-wife, Tanya, suddenly appears, begging him to move to the United States with her and their daughter, Masha. Boris explains that moving to America would feel too much like surrender. "For a writer it equals death." Tanya counters that "there are a lot of Russians there." "They are defeatists," Boris says. "A bunch of miserable defeatists.... I'm telling you again, I will not leave.... There's nothing to explain."

As if divorce, writer's block, and alcoholism weren't enough, the KGB is also on Boris's back. When they discover his wife is planning on leaving the country, they call him in for a chat. Major Belyaev tells him, "I know you're headed to Leningrad. My advice to you – don't make noise. To put it politely – zip your trap... your dossier packs more punch that Goethe's 'Faust'. There's enough on you for forty years." All these threats are aimed at a writer who has never even been published.

The preserve in "Pushkin Hills" works as kind of a microcosm of Russian life and politics – in which one's dedication to love of country is constantly being tested. Dovlatov recognizes that this sense of surreal political paranoia does have a humorous element – as James Wood puts it in his afterword, "what Gogol called 'laughter through tears.' " "As dreadful as things looked, I was still alive. And, perhaps, the last thing to die in a man is his baseness. His ability to respond to peroxide blondes and the need to write." Watching his wife chat with one of his coworkers, Boris reflects: "For some reason I always feel alarmed when two women are left alone. Especially when one of them is my wife."

Thankfully, Dovlatov was able to escape a world where a writer's ideas, even those yet unborn, could be considered a political threat. He moved to New York in 1978 and lived there until his early death of heart failure in 1990 – 12 fruitful years that resulted in twelve novels published in the US and in Europe. After his death and the fall of the Soviet Union, several collections of his short stories were finally published in Russia. One has to wonder what Dovlatov would have made of this. After all, Boris did remind his wife he loved Russia in spite of its shortcomings. "My language, my people, my country.... Imagine this, I even love the policemen."