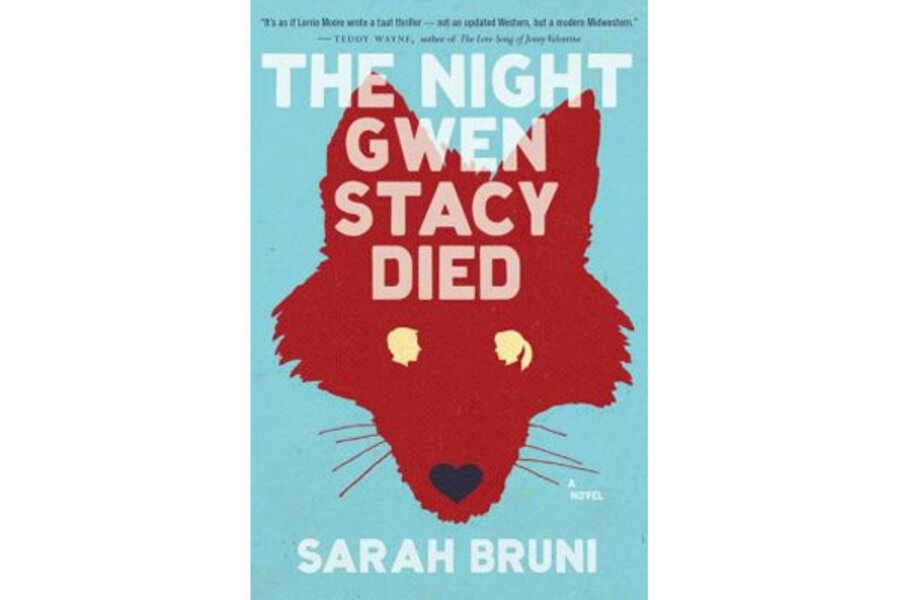

The Night Gwen Stacy Died

Loading...

Sarah Bruni’s debut novel The Night Gwen Stacy Died is about small towns, sex, coyotes, and 1970s superhero comics. It is also about how girls and boys create their identities (secret and otherwise), escape small towns (via fantasy, car, crime), and write themselves into and out of stories in which, at first glance, they appear to be only minor characters.

On the cusp of 18, Sheila Gower has one friend (“she had always preferred the company of intense and loyal outsiders”), no plans to go to college (having grown up near one of the “more modestly sized Big Ten universities in the Midwest," she “felt she had already been to college and she really hadn’t thought much of the experience”), and works nights in a gas station, where she studies French and plans to escape small-town Iowa for Paris.

In walks a slightly older boy with an I.D. (fake, she presumes) proclaiming himself to be Peter Parker, the alter ego of Spider Man. After her French teacher dashes her illusions of Paris, telling her that French people also have Burger Kings and thunderstorms and bills to pay, Peter offers her a chance to participate in his fantasy instead. Sheila thinks, “maybe this was one way to leave a place, with a boy and a gun” and agrees to roadtrip to Chicago, playing Bonnie to his Clyde.

Once on the road, Sheila discovers, to no one’s surprise, that she has been cast as Gwen Stacy, Peter Parker’s first love. She runs with it, embracing Gwen and Peter, in name, dress, and as a real-life romantic super-duo. Her lover-abductor has reasons of his own, stretching back to his boyhood, for choosing this particular plot. Being both too young and of a different gender than those typically obsessed with '70s-era Spidey comics, the lady playing his heroine doesn’t know, at first, what any teenage comics geek does: Gwen Stacy will die.

But Gwen-Sheila is not Gwen Stacy. She seems to genuinely fall in love with Peter and finds that he makes her world bigger (“Peter made her want to talk to strangers. He made her think there was something to talk about – even in Iowa”).

“Gwen Stacy never had a chance,” writes Bruni. “She could never do anything but react to the elements of the story that befell her.” But Sheila insists on an equal role in their story, telling Peter,“This thing we are together – you don’t own it.”

She improvises her lines, takes action, and rewrites the script. As she is told by a pack of possibly mystical and occasionally articulate coyotes who dog her throughout the story, “If you are reading the signs, you are writing the signs – they say what you see in them.” From the elements of retro boyhood camp, teenage girlhood, and love vigilantes, Bruni forges a modern, subversive, original story of her own