My Lunches with Orson

Loading...

Orson Welles is a larger-than-life figure, revered by film aficionados and known to a wider audience for his masterpiece, "Citizen Kane."

Less familiar is his descent over the last three decades of his life from the fame and fortune he skyrocketed to as a young man in the 1930s theater world. Even "Citizen Kane," despite its critical acclaim, was a financial flop, and his subsequent film "The Magnificent Ambersons" became both a commercial and critical failure after the studio sliced 45 minutes off Welles’s original cut and tacked on a schlocky happy ending while he was abroad.

Despite memorable performances in "The Third Man" and "A Touch of Evil," his career plummeted, culminating in minor roles in forgettable films and a stint as a spokesperson for Paul Masson wine. Sadly, you can find Welles’s drunken outtakes on YouTube.

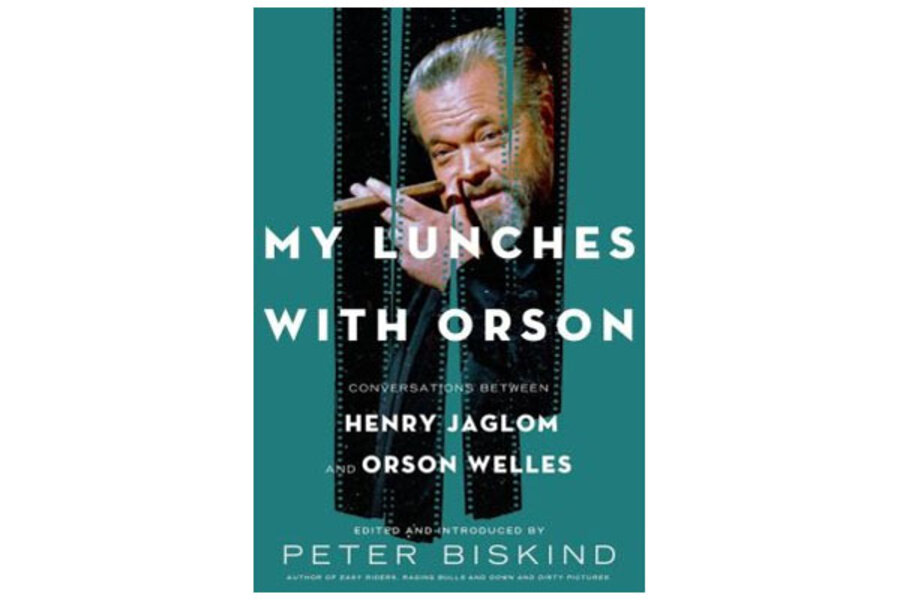

My Lunches with Orson goes some way toward explaining this downward spiral by shedding light on the personal foibles that hindered Welles’s mammoth creativity and the ways that Hollywood’s studio machine blocked him at every turn. Edited by film historian Peter Biskind, the book consists of conversations with Welles’s close friend, fellow director Henry Jaglom, recorded over lunch between 1983 and 1985, the final years of Welles's life.

That Jaglom became Welles’ de facto agent, angling for support for Welles’s projects and soliciting stars to perform in them, speaks to his desire to rescue him from the weird ignominy of his post-"Kane" career – and that Welles's final role was that of the “friend” in one of Jaglom’s films is fitting.

Ironically, the last film Welles tried – and failed – to make was "King Lear." Here, in "My Lunches with Orson," Jaglom plays the Fool to Welles’s fallen king. (Although Jaglom is accomplished in his own right, having edited "Easy Rider," which launched the careers of Jack Nicolson, Peter Fonda, and Dennis Hopper).

Instead of the moors, the tragedy takes place in the Hollywood-chic restaurant Ma Maison, where Jaglom listens as Welles relives his golden days, bemoans his fate, and grasps at some illusory possibility of a comeback, which we know will ultimately elude him.

The pairing of an iconic mentor with a receptive listener echoes "My Dinner with Andre," the film that Biskind’s title alludes to, but whereas director André Gregory’s reflections tend toward the boyishly optimistic, delivered by a man in love with life and the theater, Welles emerges as a tragicomic figure, presiding over his favorite corner table with his poodle Kiki, dismissing overtures from stars as varied as Elizabeth Taylor and Zsa Gabor, alternating between pathos, gossip, deliberate provocation (“I’m a racist, you know”) and insights on politics and culture.

In a moment of striking prescience, he observes, “America has missed absolutely no opportunity, not only during the Reagan administration, but in my lifetime, to render it impossible for us to be anything but the deathly enemy of all Arabs.... We can never polish that image. I don't care how much money we pour into it.” Touché.

Yet somehow Welles and Jaglom arrived at this subject via an exchange about "The Love Boat." The book is full of such odd juxtapositions of the profound and insipid. Welcome to Hollywood.

It’s most pleasurable to read Welles’s reflections on "Kane" or projects like "The Cradle Will Rock," "The Third Man," and the idiosyncratic "F is for Fake," and I wished the conversations included more of Welles on his own work. (Biskind’s introduction does a nice job of narrating the arc of his career, bridging some gaps.)

Welles’s commentary on other celebrities can be witty, but speaks mainly to his aggrievements. Admirers may enjoy his anecdotes and barbs, but will likely echo Jaglom’s frustration at the projects he conceived and never realized, or the parts he turned down, such as the husband in George Cukor’s "Gaslight."

"My Lunches with Orson" also offers the experience of sitting in on a particular historical-cultural moment – a time when the biggest stars were Nicholson, Beatty, and Reynolds, and the latest technology was “these laser discs and video things.” Read with your Netflix on hand, as Welles’s wealth of knowledge inspires re-viewings of both his own films and those of his favorite actors like Buster Keaton and Carol Lombard.

Learning about the obstacles Welles faced in Hollywood also inspires an appreciation for the venues for independent film that exist today. Had he been around for the explosion of indies and the creation of IFC and the like, Welles would have undoubtedly had a more satisfying career, while still maintaining the integrity of his unique vision.