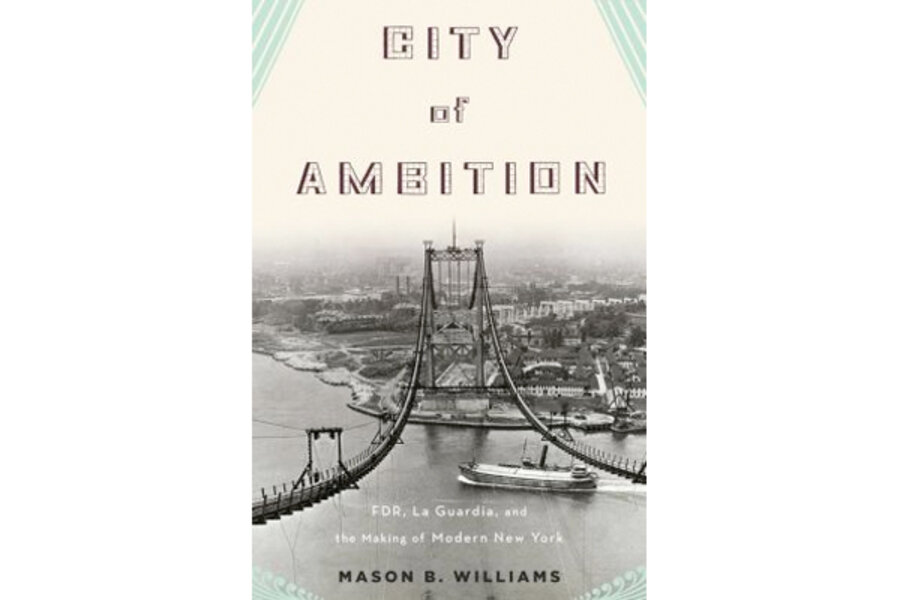

City of Ambition

Loading...

During his presidency, Franklin Delano Roosevelt remarked of New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, "Our Mayor is the most appealing man I know. He comes to Washington and tells me a sad story. The tears run down my cheeks and the tears run down his cheeks and the next thing I know, he has wangled another $50 million out of me."

FDR was being playful, but there was truth in his quip, as historian Mason Williams demonstrates in his first book, the compelling if occasionally leaden City of Ambition: FDR, La Guardia, and the Making of Modern New York. "City of Ambition" traces the unique Depression-era collaboration between the two formidable politicians, who, the author says, became "more closely associated in the public mind than any mayor and president had ever been."

Williams devotes too much ink to the details of La Guardia's early career as a US congressman, but the book picks up when the focus shifts to his New York mayoralty, which spanned the depths of the Depression and World War II. The heart of the book concerns the impact of federal relief on the creation of modern New York.

The "physical legacy of the New Deal still pervades the city," Williams observes, and indeed, that legacy is extraordinary. The New Deal agencies the Civil Works Administration, the Public Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration together financed the Lincoln and Queens-Midtown tunnels, the Triborough Bridge, the Belt Parkway, La Guardia Airport, numerous subway extensions, and the campuses of Brooklyn and Hunter colleges.

They bankrolled the construction of public housing, schools, and neighborhood health clinics, and, under the legendary city parks commissioner Robert Moses, funded the creation, expansion, and refurbishment of park space, playgrounds, beaches, swimming pools, and sports facilities, democratizing access to recreation for a populace greatly demoralized by the Depression.

Ironically, the 1930s, the author notes, "ended with the public property of the city in perhaps the best physical condition in its history."

Williams attributes this astounding productivity in large part to the partnership between Roosevelt and La Guardia, men who, despite hailing from different backgrounds, having very different styles, and belonging to different political parties, shared a conviction that robust executive leadership could make government a bold, constructive force for the common good.

FDR had come to believe that massive unemployment would be best addressed by the federal government's subsidizing of municipal programs that put the jobless back to work. The national government had not up to that point been a visible force in state and local affairs, but cultivating a strong relationship with Washington was an early priority of the Republican anti-Tammany reformer La Guardia, who stormed into office in 1934 with a burst of activity. ("It was as though a hundred short men in black Stetsons had been loosed upon the city," one citizen recalled of the Greenwich Village–born but Arizona-raised mayor's seeming ubiquity, in the type of vivid image too rare in the book.)

At the start of his mayoralty, sending his commissioners to meet with FDR's cabinet members, La Guardia noted of federal-municipal partnerships, "The possibilities are tremendous. The surface has not even been scratched." Most American cities benefited from New Deal largesse, of course, but Williams notes that La Guardia worked hard to maximize Gotham's piece of the pie. He was successful: "At the peak of the New Deal," Williams writes, "federal spending on projects sponsored by New York's municipal departments ... totaled more than 30 percent of the city's annual budget."

The friendly and productive relationship between the patrician Democratic president and the pugnacious Republican mayor served them both well. Roosevelt could rely on the mayor to cross party lines and campaign energetically for him, support that FDR valued amid growing conservative opposition to the New Deal.

Meanwhile, the ambitious and publicity-hungry La Guardia cherished the widely held belief that he and the president shared a special bond. As the US entered World War II, he desperately wanted his loyalty to be rewarded with either an appointment as secretary of war – which Roosevelt had all but promised him – or a high-ranking military commission, but several Roosevelt advisers opposed any such move, with Harold Ickes, for one, warning against La Guardia's "dramatic qualities."

The president strung La Guardia along for a while ("I still believe General Eisenhower can not get along without me and am awaiting your order," the mayor wrote FDR pitiably at one point) but ultimately only offered the mayor a generalship that La Guardia rejected because he felt it lacked sufficient authority.

Despite the bitterness of that blow and the resultant cooling in their friendship, La Guardia spoke movingly of Roosevelt after the president died in 1945. Weeks later, the mayor, himself in ill health, announced that he would not seek a fourth term. He died not long after, in 1947, prompting former vice president Henry Wallace to say, "First Roosevelt, now Fiorello – the fighters are taken from us when we need them most, but the fight continues."

In our era of toxic partisanship and distrust of government, it is difficult to imagine the fight ever again being waged in quite the same way.

Barbara Spindel has covered books for Time Out New York, Newsweek.com, Details, and Spin. She holds a PhD in American Studies.