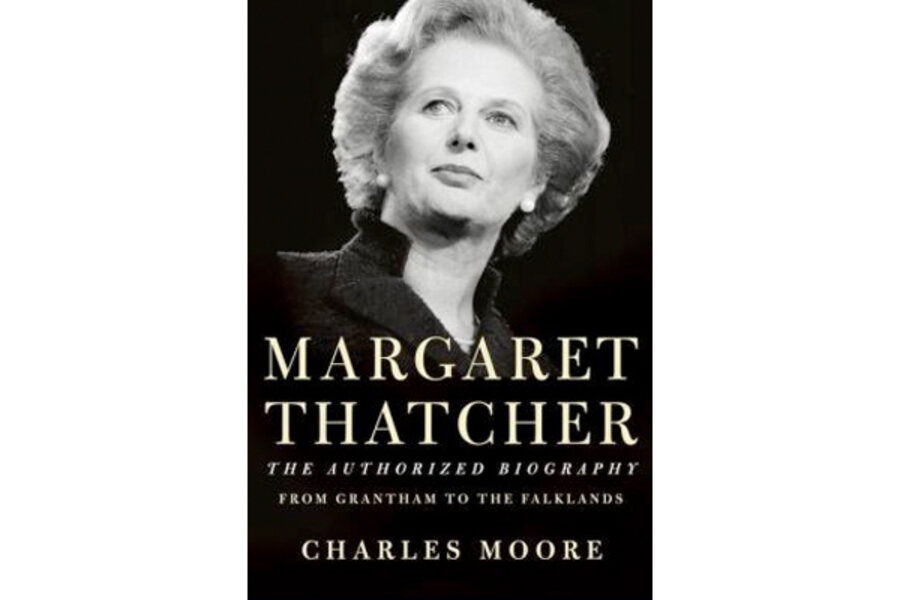

Margaret Thatcher: From Grantham to the Falklands

Loading...

Appearing mere weeks after the April 8 death of Lady Margaret Thatcher, British journalist Charles Moore’s authorized biography of Thatcher is no rush job. He essentially completed the two-volume project long before Thatcher’s death, with the understanding that the book wouldn’t be released until after the former prime minister had died. Her passing triggered the release of Volume I in Britain shortly after her funeral, and the first installment of Moore’s series is now available to American readers through this U.S. edition.

Moore is aware that as an “authorized biography,” his account of Thatcher’s life and career will invite obvious questions about its objectivity. Luckily, From Grantham to the Falklands isn’t an exercise in political hagiography. As Moore explains, Thatcher selected him to write her story and gave him full access to herself for interviews as well as to her papers. She also helped him with requests for interviews of those who knew her best, including her friends, political associates, and family members. Moore writes that his book “is described as an ‘authorized’ biography, because Mrs. Thatcher asked me to write it, but our agreement also stipulated that Lady Thatcher was not permitted to read my manuscript and the book could not appear in her lifetime. This was partly to spare her, in old age, any controversy that might result from publication, but mainly to reassure readers that she had not been able to exert any control over what was said.”

Moore uses his freedom to good advantage. Although his depiction of Thatcher is generally sympathetic, he keeps his subject at arm’s length, and critical observations abound. One of the abiding themes of the book is that Thatcher, like her friend and fellow conservative, Ronald Reagan, had a genius for being underestimated. He includes the story of a political insider who assumed Thatcher was retaining very little of what he was telling her, only to discover that she had perfect recall of the complicated policy data he had shared.

But Moore adds that Thatcher was better at promoting ideas than generating them. “Strictly thinking, Mrs. Thatcher was ill equipped for intellectual battle,” he tells readers. “Despite the brisk efficiency for which she was renowned, she did not have an intellectually orderly mind; nor did she have an original one. Rather than developing ideas of her own, she was a sort of ‘stage-door Johnny’ for the ideas of others – admiring, overexcited. But this was not in fact, a handicap.” He quotes Thatcher adviser Alfred Sherman: “She wasn’t a woman of ideas... she was a woman of beliefs, and beliefs are better than ideas.”

Although Thatcher served as the first female prime minister of Great Britain from 1979 to 1990, Moore refers to her as “Mrs. Thatcher” throughout much of his narrative because “that is what people called her, and the word “Mrs.” was very important in their minds.”

It’s a reminder that even as the leader of a major power, Thatcher was still touched by traditional ideas about womanhood. In documenting the Thatchers’ domestic life, for example, Moore notes that in accordance with government rules, the prime minister and her husband, Denis, were given no household staff to clean their government residence or cook meals. Because Denis was too old-fashioned to think about providing meals for himself, supper duties often fell to Thatcher, who frequently resolved the issue by ordering convenience foods from down the street.

Thatcher could, Moore writes, use longstanding cultural assumptions about women to her advantage. Upon her election as leader of the Conservative Party in 1975, she played upon the consensus among her critics that she was “a little girl lost,” telling allies that “she was a frail little woman who needed the help of strong men such as they. She was not as vulnerable as she wished to seem, however. She had a burning sense of mission.”

That mission included an affirmation of free market principles to stir Britain’s renewal, a philosophy that advanced Thatcher as an icon of conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic. But Moore suggests that as a politician, Thatcher wasn’t nearly as radical as many of her sharpest critics – and most fervent admirers – claimed her to be. “She did not believe that the bureaucracy should be reshaped from top to bottom,” he writes, “but rather that it should be regalvanized.”

As an author, Moore follows the Robert Caro school of factual exactitude, as when he parses recollections of the supper menu at No. 10 Downing St. on Thatcher’s first day of office by noting that some remembered cottage pie, while others instead remembered sandwiches and others recalled shepherd’s pie. Such descriptive notation, often laid out in copiously detailed footnotes, can make Moore sound more like a recording secretary than a biographer.

Moore’s primary strength – a thorough grounding in British culture and politics – can also be a complication for American readers. His references to British parliamentary customs might confuse those less well versed in these traditions, and the book contains a number of British idioms, as when he uses the word “poky” to describe the relative smallness of the Thatchers’ living quarters.

“From Grantham to the Falklands” ends with Thatcher offering a victory speech after her country’s successful military campaign to eject Argentine forces from the Falkland Islands.

“It may well have been the happiest moment of her life,” Moore writes – hinting, without quite saying so, that Volume II of his biography could be an anti-climax.

Danny Heitman, an author and a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is an adjunct professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication.