Exiled to Nowhere

Loading...

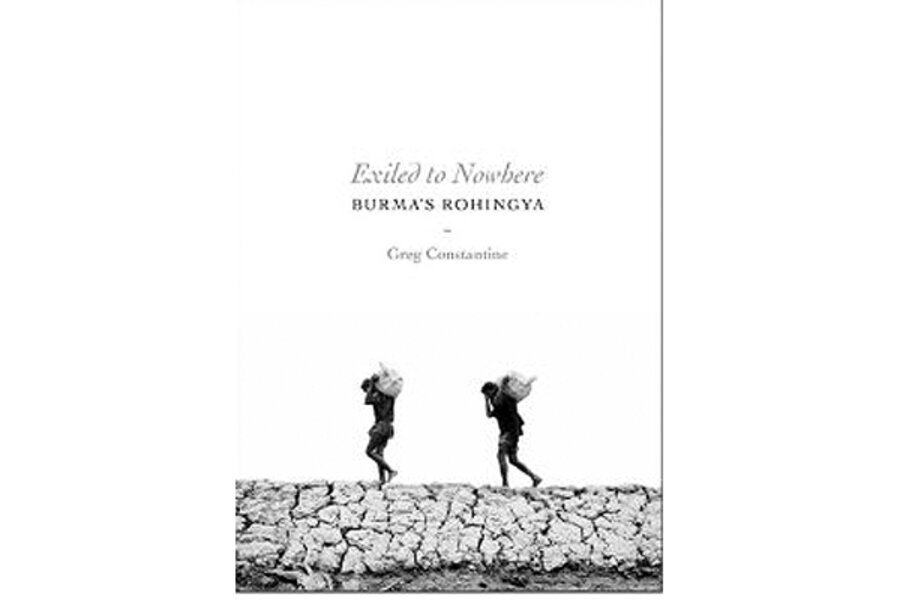

In Exiled to Nowhere, photographer Greg Constantine tells in pictures the little-known story of the Rohingya, a stateless ethnic minority in Burma who have long been denied the most basic human rights.

For nearly half a century, Burma has resisted recognizing the Rohingya as one of the country’s indigenous groups. And so far, Burma’s recent opening up and reforms have done little to change the situation. As the writer Emma Larkin explains in a foreword to "Exiled to Nowhere," the Rohingya trace their origins back to Arab traders who arrived in northwestern Burma as early as the ninth century. But Burmese scholars and historians dispute the existence of even the word Rohingya prior to 1950. They call them “Bengalis,” which in effect designates them as foreigners. They claim that while the British encouraged their migration into Burma during colonial times to work in agriculture, many of today’s Rohingyas are recent immigrants from Bangladesh.

Few of the country’s estimated 800,000 Rohingyas have been allowed to gain Burmese citizenship. They cannot travel beyond their own villages without permission. Their marriages require government approval, and they cannot enroll their children in regular schools. Rohingya men have provided forced labor to the army and local security forces. Rohingya women have been subjected to sexual harassment. The Rohingya have for decades been largely ignored by the international community except for the work of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

All of that changed in early June this year when communal clashes involving the Rohingya and the Rakhine ethnic group erupted in western Burma in early June of this year. Both the Muslim Rohingya and the local Rakhine Buddhists suffered serious casualties, about 80 killed in total, by official count. Human rights groups say that the figure is likely to have been much higher. In late October, the violence erupted again, with at least 64 killed by official count and thousands of homes destroyed by fire.

Tensions and fears on both sides are still high, and another round of unrest could erupt at any time. Constantine’s book focuses on the nearly 300,000 Rohingyas who have fled to neighboring Bangladesh, many of them leaving Burma after the junta led by General Ne Win launched a purge of “illegal foreigners” in 1978. In Rakhine, this resulted in widespread brutality, including mass arrests targeting the Rohingya population. Some 250,000 Rohingya refugees then flooded into Bangladesh. These refugees are now targeted by the Bangladesh government as unwanted and they have suffered from periodic attempts to shut down the crowded refugee camps in which they have sought shelter. Following the June violence, hundreds of Rohingyas attempted to flee to Bangladesh in boats across the narrow Naf River and by sea. Bangladesh border guards forced them back. A few escaped into hiding in Bangladesh.

Constantine introduces us first to a 34-year-old Rohingya man named Jafar, who has spent more than half his life in a refugee camp in Bangladesh “with no country to belong to.” Jafar was born in 1978, the year that General Ne Win launched his ethnic cleansing operation.

“Myanmar is my home and that is where I want to go back to,” Jafar says. “But none of us has citizenship, and without citizenship we are like a fish out of water….”

A female refugee, Fatima, describes the treatment of the Rohingya by NaSaKa, a security force established in 1992 that includes elements of police, immigration, customs, and military intelligence units. In 1994, the Burmese authorities issued an order that required Rohingyas wishing to marry to first receive permission from NaSaKa. The order was issued nowhere else in Burma. Those who disobey the order can still be arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned for up to 10 years. Couples must usually pay extortion money and often have to wait years for permission to be granted. They must also sign a statement saying they will have no more than two children.

“First they demanded money from my husband’s parents, then they demanded money from my parents,” says Fatima. “My parents didn’t have the money, so we paid them by giving them our cattle and land. Then the officials told me, ‘You have to have an abortion, otherwise we will send you to prison.'” In the end, Fatima had two abortions. Her husband spent six months in jail, where he was beaten and tortured. When he got out of prison, the officials told her that she had “committed too many crimes” and had no right to be married. Penniless at this point, the couple had no choice but to leave the country.

Constantine also provides a useful four-page historical timeline for those not familiar with the Rohingya. It starts with 1799 and the first historical document mentioning the “Rooinga,” today’s Rohingya. It notes that the British invaded Arakan, the historical name for Rakhine state, in 1823. During the following decades, a large number of people – mostly Muslims from the Chittagong region – migrated from the Indian subcontinent into Arakan.

In 1942, the Japanese drove the British out of Arakan, leaving a vacuum. Interethnic clashes erupted between Arakanese Muslims and Buddhists, splitting Arakan into a division that still exists today, leaving mostly Buddhists in the south and mostly Muslim Rohingya in the north. Recent developments have dramatized the difficulties of finding a solution. Burma’s President Thein Sein came under international criticism this summer after he suggested that the UN’s refugee agency take responsibility for the country’s Rohingya and that they should be deported. The UN agency rejected his proposal, but thousands of Buddhist monks took to the streets in several cities to back his call, saying the Rohingya do not belong in Burma.

It’s safe to say that many Burmese despise the Rohingya, making any reconciliation difficult to achieve. But the government has also set up a commission to investigate the causes of the June violence that includes a number of respected intellectuals and religious leaders.

Constantine’s book goes a long way toward showing the human face of the Rohingya through more than 80 black-and-white photographs. The photos show not only crowded conditions in Rohingya refugee camps but also the resilience of a people who are willing to work for less than $3 a day in salt fields or even for $1.50 a day drying fish at local Bengali markets. In one area, Rohingya men have become bonded laborers, trapped into debt by Bangladeshi boat owners.

Most compelling perhaps are the faces of those of all ages – from infants to grandparents – whom Constantine has captured on film. In one of them, a grandmother holds a small child, who almost certainly faces a future without education and at best work as a low-paid child laborer. Another photo shows eight refugees – a mother, father, and grandmother among them – holding and comforting several children. Their expressions tell you that they are utterly tired, lost, and confused.

Publication of the book was supported in part by funding from Refugees International.

Dan Southerland, executive editor of Radio Free Asia, is a former Monitor correspondent and a former Beijing bureau chief for The Washington Post.